Ismail Kadare

“I had three choices: to conform to my own beliefs, which meant death; complete silence, which meant another kind of death; to pay a tribute, a bribe. I chose the third solution by writing The Long Winter.”

“I had three choices: to conform to my own beliefs, which meant death; complete silence, which meant another kind of death; to pay a tribute, a bribe. I chose the third solution by writing The Long Winter.”

“I believe that political correctness can be a form of linguistic fascism . . . The only way to react is to get up in the morning and start the day by saying four or five vastly politically incorrect things before breakfast!”

“There is an important erotic element in A Thousand and One Nights, which is one of the keys to understanding the Orient.”

“English has more flexibility. It’s a very plastic, very shapeable, very expressive language. In that sense it feels quite natural.”

“I know that black life, like all life, outstrips our perceptions, that so much of black life still remains—to invoke Ellison here—invisible, unseen.”

“I declare to all young men trying to become writers that they do not actually have to become drunkards first.”

“Until I can read a story physically, with the eyes, it doesn’t seem to exist for me.”

“You have to be humble enough to accept that you’re secondary to the author, and yet have enough chutzpah to take that other language and transform it.”

“People who didn’t live pre-Internet can’t grasp how devoid of ideas life in my hometown was. I stopped in the middle of the SAT to memorize a poem, because I thought, This is a great work of art and I’ll never see it again.”

“When I was a child, everything used to come to me first as a poem.”

“Humor needs to come in under cover of darkness, in disguise, and surprise people.”

“You have to beat your own problematic imagination to discover what it is you're saying and how to say it and move forward into the unknown.”

“Goddamn it, FEELING is what I like in art, not CRAFTINESS and the hiding of feelings.”

“I tried to depict the human face of this history, I wanted to write a book that people would actually want to read.”

On a true fool natural: “He never stops being a fool to save himself; he never tries to do anything but anger his master . . . Hunter Thompson is a fool natural. Neal Cassady was a fool natural, the best one we knew.”

“What’s a revolution? It’s when a regime can no longer control the populace, when the regime is brought down to the ground.”

“I suppose that my work is always mourning something, the loss of a paradise—not the thing that comes after you die, but the thing that you had before.”

“They did type me as a horror writer, but I have been able to do all sorts of things within that framework.”

On feminism: “It's a point of view; it's a stance; it's an attitude towards life that affects, and afflicts, everything I do.”

“I’ve always felt that there’s a very thin membrane between madness, alcoholism, and/or destitution and being an OK American guy in a comfortable heated apartment with meatballs and a decent Sauvignon Blanc in the fridge.”

“I believe that the evidence for telepathy is overwhelming and that it is a part of reality that is above science. Science allows us to glimpse [only] fragments of reality.”

“[Nabokov’s] language is made visible . . . like a veil or transparent curtain. You cannot help seeing the curtain as you peek into the intimate rooms behind.”

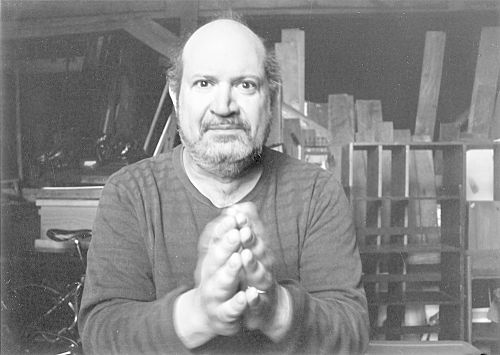

László Krasznahorkai was born in 1954 in Gyula, a provincial town in Hungary, in the Soviet era. He published his first novel, Satantango, in 1985, then The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), War and War (1999), and Baron Wenckheim’s Homecoming (2016).

“The great European novel started out as entertainment, and every true novelist is nostalgic for it. In fact, the themes of those great entertainments are terribly serious—think of Cervantes!”

“One critic wrote . . . that my poems sounded as though they had been translated from the Hungarian. I don’t know why, but somehow that made me feel quite lighthearted.”

“In some ways [the Internet]’s definitely an enemy.”

“If a word that was used by Flaubert or Césaire falls into desuetude, if it becomes passé, we still keep it in the dictionary because it was used by an important writer.”

“I seldom know where I’m headed, but if the story is meant to be, you cross over to the other side—you’re inside it, and there’s an engine.”

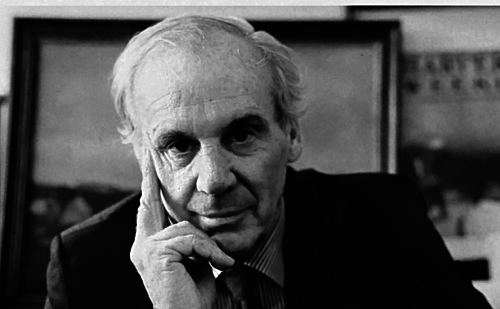

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

By the time I arrived in New York in the late seventies, Lapham was established in the city’s editorial elite, up there with William Shawn at The New Yorker and Barbara Epstein and Bob Silvers at The New York Review of Books. He was a glamorous fixture at literary parties and a regular at Elaine’s. In 1988, he raised plutocratic hackles by publishing Money and Class in America, a mordant indictment of our obsession with wealth. For a brief but glorious couple of years, he hosted a literary chat show on public TV called Bookmark, trading repartee with guests such as Joyce Carol Oates, Gore Vidal, Alison Lurie, and Edward Said. All the while, a new issue of Harper’s would hit the newsstands every month, with a lead essay by Lapham that couched his erudite observations on American society and politics in Augustan prose.

Today Lapham is the rare surviving eminence from that literary world. But he has managed to keep a handsome bit of it alive—so I observed when I went to interview him last summer in the offices of Lapham’s, a book-filled, crepuscular warren on a high floor of an old building just off Union Square. There he presides over a compact but bustling editorial operation, with an improbably youthful crew of subeditors. One LQ intern, who had also done stints at other magazines, told me that Lapham was singular among top editors for the personal attention he showed to each member of his staff.

Our conversation took place over several sessions, each around ninety minutes. Despite the heat, he was always impeccably attired: well-tailored blue blazer, silk tie, cuff links, and elegant loafers with no socks. He speaks in a relaxed baritone, punctuated by an occasional cough of almost orchestral resonance—a product, perhaps, of the Parliaments he is always dashing outside to smoke. The frequency with which he chuckles attests to a vision of life that is essentially comic, in which the most pervasive evils are folly and pretension.

I was familiar with such aspects of the Lapham persona. But what surprised me was his candid revelation of the struggle and self-doubt that lay behind what I had imagined to be his effortlessness. Those essays, so coolly modulated and intellectually assured, are the outcome of a creative process filled with arduous redrafting, rejiggering, revision, and last-minute amendment in the teeth of the printing press. And it is a creative process that always begins—as it did with his model, Montaigne—not with a dogmatic axiom to be unpacked but in a state of skeptical self-questioning: What do I really know? If there a unifying core to Lapham’s dual career as an editor and an essayist, that may be it.

—Jim Holt

INTERVIEWER

You started your career with the San Francisco Examiner.

LEWIS LAPHAM

My reasons for going into the newspaper business were twofold. One, to learn how to write. When you’re young you tend to use too many adverbs and adjectives, to think every word you come up with deserves to be engraved in marble. I hoped to cure myself of the habit acquired while writing papers at school and college.

The other reason was to get an education. Having grown up in Pacific Heights in San Francisco and then gone to prep school in Lakeville, Connecticut, and to Yale College, I knew I’d been living in a privileged, safe space and didn’t know much of anything about the rest of the country. Didn’t know how the politics worked, where the water came from, how the garbage was collected, who was living on the wrong side of the tracks. As a newspaper reporter, I expected to learn who were my fellow citizens, where and what was the American democracy.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s back up. Your grandfather was the mayor of San Francisco when you were a boy.

LAPHAM

Also a shipowner, the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company. Intercoastal trade. The ship would start with dry cargo in Seattle, go down the West Coast, through the Canal, around the Gulf, up the East Coast to Portland, Maine, and then back on reversed compass bearings. A very profitable business before the interstate highway system. On December 7, 1941, we owned a substantial fleet of ships. In early 1942, the United States government commandeered all of them for the North Atlantic convoys. Most of them were sunk by German U-boats. If I remember the story correctly, we were never reimbursed for the loss.

INTERVIEWER

As a boy, what were your passions? You must have read widely.

LAPHAM

Books were my boyhood. I can remember my mother reading Moby-Dick to me when I was six years old. Each evening I had to know exactly where the story had left off the night before or she wouldn’t read the next page. So I learned to stay with it. My father had a large library, he was himself a constant reader.

INTERVIEWER

And a writer, too. He was a columnist for the paper, right?

LAPHAM

Had been, yes. My father came back to San Francisco after graduating from Yale in 1931 to work for the Examiner, on occasion speaking directly to William Randolph Hearst, then enthroned at San Simeon. Under pressure from my grandfather, my father gave up journalism to become president of the family company.

And then my grandfather was elected mayor in 1942. He sometimes would go out to meet the aircraft carriers coming in from the war in the Pacific, take me with him in the launch, bring me up to the bridge to meet an admiral. When I was ten years old I wanted to become a navy carrier pilot. At Yale I didn’t qualify for the naval reserves because I was color blind.

INTERVIEWER

So what did you do?

LAPHAM

I was also in love with words. I tried my hand at poetry at Yale, and later at Cambridge in England, attempted to write in imitation of Yeats, Auden, Donne, Shakespeare, and A. E. Housman.

INTERVIEWER

The poetry you wrote back then, it scanned?

LAPHAM

It did. At Yale I discovered classical music and that also was an influence.

INTERVIEWER

You were already trained as a pianist?

LAPHAM

No. The house in San Francisco offered a fine view of the bay, but it wasn’t furnished with a piano. My parents listened on the Victrola to Cole Porter, Fred Astaire, and the Great American Songbook. At Yale I met Beethoven, Bach, Handel, and Mozart.

INTERVIEWER

Who was the first composer that moved you?

LAPHAM

My first lessons were on the harpsichord because I wanted to play Bach.

INTERVIEWER

So when you went on to Cambridge, you had an amateur interest in music and keyboard. You were there to study history.

LAPHAM

Medieval English history. At Magdalene College, I met C. S. Lewis, who had just come over from Oxford. I met Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Admired the poetry of Robert Graves, wrote him letters in Majorca. He didn’t write back.

At Cambridge, I was never in any kind of inner circle. I wandered around, audited lectures, wrote poetry, acted in plays. It was a lovely year, but I understood at the end of it I was not a scholar. I didn’t have the patience for footnotes. My parents were unwilling to fund my further education unless I was going to make an academic career.

“The good effect of translating is this cross-pollination of languages.”

“A writer once said to me, If you ever go to America, go either to the East Coast or the West Coast: The rest is a desert full of bigots. That's what I think I'd like . . . a version of pastoral.”

On his father: “If I asked him for money, he'd say, ‘Are you going to publish some more of those books that I can't understand?’ And I'd say, ‘Yes.’ And he'd give it to me.”

“[Gertrude Stein] really needed someone like Virgil Thomson, whom she respected, to sit on her a bit and make her devise some plot.”

“The one thing you can bet is that spying is never over. Spying is like the wiring in this building: It's just a question of who takes it over and switches on the lights. It will go on and on and on.”

“One of the things [fiction] does is lead you to recognize what you did not know before.”

“I wouldn’t say that I dislike the young. I’m simply not a fan of naïveté.”

“Some cynical biographer said to me, Make sure it’s a good death. Make sure you’re not picking someone who just declined.”

“The novel will never die, but it will keep changing and evolving and taking different shapes . . . Nowadays, there are too many books and not enough good ones.”

“[Some people think] that storytelling is telling jokes. So they have to be discouraged! Then others think that storytelling—is like an encounter group . . . ”

“I’m gregarious with writers and never with manuscripts . . . I [like to] create the illusion of seamless perfection, so I alone know the flawed homely process along the way.”

“I have many times been praised for my lack of animosity towards the Germans. It's not a philosophical virtue. It's a habit of having my second reactions before the first.”

“. . . whoever you are, you've got to start from where you are. If you're a sailor, and only know sailor's language, well, write in it, for God's sake.”

On having his testimony discounted in court: “How can a poet or fiction writer tell the truth in court if he or she can't present the events in a meaningful sequence, which is what a story is? The message is, Stay out of court.”

“The book attained a mind of its own, a subjectivity or an autocatalytic machinelike quality.”

“I want to create absurd and hilarious, but also dark and revealing, edifices of language.”

“I’ve got the fucking gift for it. Instinct, call it.”

“A novel should reflect its society and its circumstances.”

Quoting Neruda: “I have a chest full of all the insults, villainies, and infamies a man is capable of withstanding. . . . If you become famous, you will have to go through that.”

On American English: “It seems to me that the contrast between adjacent syllables has lessened and the result is an over-reliance on enjambment. Now enjambment is a fine, intellectually strong aid, but like all such things it becomes tiresome and calls too much attention to itself.”

“Most poetry is very formal, but when a modern poet is formal he gets more attention for it than old poets did.”