Ismail Kadare

“I had three choices: to conform to my own beliefs, which meant death; complete silence, which meant another kind of death; to pay a tribute, a bribe. I chose the third solution by writing The Long Winter.”

“I had three choices: to conform to my own beliefs, which meant death; complete silence, which meant another kind of death; to pay a tribute, a bribe. I chose the third solution by writing The Long Winter.”

“I recognize limitations in the sense that I’ve read Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and Shakespeare … Aside from that I don’t think of limiting myself.”

“The real event of the 1980s was . . . the emergence of great looting fortunes . . . which made us revise the value of everything—not to the benefit of society . . . ”

“Those who have earned respect should be given respect, regardless of their human faults.”

“That is the dream of all novelists—that one of their characters will become ‘somebody.’”

“I don't for a minute think that Hitler is like Joan of Arc. But I think that at that deep level of tropisms, Hitler or Stalin must have experienced the same tropisms as anyone else.”

“[In old age] there is a childlike innocence, often, that has nothing to do with the childishness of senility. The moments become precious . . . ”

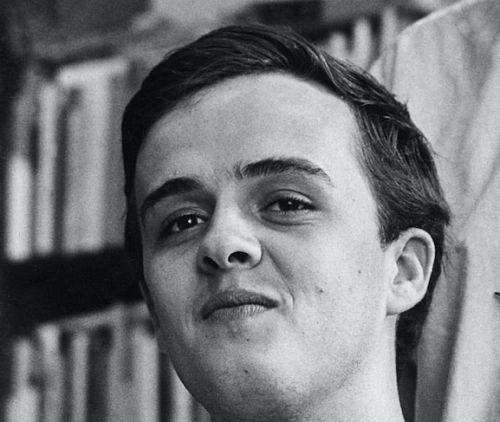

My first meeting with George Saunders took place in his home of ten years, a ranch house in the Catskills. The house stood on fifteen acres of hilly woods, crisscrossed by narrow paths that he and his wife, the novelist Paula Saunders, had cleared over many afternoons, following mornings spent writing.

The Saunderses had lived in upstate New York for three decades; they raised their two daughters in Rochester and Syracuse, two of the region’s Rust Belt cities, and Saunders’s first three story collections, CivilWarLand in Bad Decline (1996), Pastoralia (2000), and In Persuasion Nation (2006), are marked by the experience of bringing up children and holding down jobs in a postindustrial economy. But the stories aren’t constrained by the conventions of gritty realism. There are ghosts, zombies, prosthetic foreheads, and memories uploaded onto computers straight from human brains. Many of the stories are extremely funny, many have endings of great emotional power, and most are written in a style that’s spare, vernacular, and very catchy. Appearing in The New Yorker since 1992, they won Saunders a MacArthur Fellowship in 2006 and have exerted an enormous influence on contemporary American fiction. The many writers who love Saunders often complain that it takes great effort not to imitate him.

In recent years, Saunders, too, has worked to write less like Saunders. Tenth of December (2013), shortlisted for a National Book Award, found him experimenting with new voices; in one story, “Escape from Spiderhead,” the narrator imbibes a drug that causes him to compose sentences in the style of Henry James. Saunders followed that book with his first novel, Lincoln in the Bardo (2017), set in nineteenth-century Washington, far from the futuristic office parks and theme parks of his early work. It debuted at the top of the New York Times best-seller list and won that year’s Man Booker Prize.

Saunders and I spoke in his kitchen over mugs of strong coffee. Furniture was sparse, because he and Paula were moving. They’d decided to sell the place and live full-time in their house outside Santa Cruz, California. But the shed where he wrote Tenth of December and Lincoln was still as it had been when he was working on those books. His desk, flanked by bookshelves, faced a table displaying perhaps ten framed photos of Buddhist teachers in robes.

“I see my writing on imagination and on war as continuous. Or rather, the two subjects are essentially locked in combat.”

Anyone else might have easily written off a life of Véra Nabokov as impossible. In the two major biographies of her husband—both written during her lifetime, when she controlled access to his papers—she is a cipher.

“When On the Waterfront succeeded ... I began to feel, Jesus, you can do the same thing in film that you can do in a book.”

“In English the expression ‘ancient Greece’ includes the meaning of ‘finished,’ whereas for us Greece goes on living, for better or for worse; it is in life, has not expired yet.”

“I was left with myself and had to do the one thing I could to survive. I knew it would be difficult to write, very difficult, but I set about doing it.”

“When I write, I make my memories tangible, and in this way I can get rid of them.”

“[The inspiration that comes to authors of fiction] is not an act of intelligence.”

“I always had this feeling—I've heard other Jews say—that when you can't find any other explanation for Jews, you say, ‘Well, they are poets.’”

On the New York theater audience: “I have a fine play in mind I’ll write for them someday. The curtain slides up on a stage bare except for a machine gun facing the audience, then the actor walks upstage, adjusts the machine gun, and blasts them.”

“The most brilliant example [of good editing] in our time

. . . was Ezra Pound’s editing of The Waste Land, which made the poem infinitely better.”

“I love going to plays. There’s a subconscious side to it, obviously–some people like to be spanked for XYZ psychological reasons, and I like to go to plays, and I can’t entirely explain why.”

“I hate endings. Just detest them. Beginnings are definitely the most exciting, middles are perplexing and endings are a disaster.”

“The fact is that we are I don’t know how many millions of people, yet communication, complete communication, is completely impossible between two of those people.”

“A ‘truth’ detached and purified of pleasures of ordinary life is not worth a damn in my view. Every grand theory and noble sentiment ought to be first tested in the kitchen—and then in bed, of course.”

“I don't like uniforms. I don't like people abdicating their identity to become part of some group, and then becoming obsessed with this and making capital of it . . . ”

“In general, I distrust philosophy. Plato recommended chasing poets from the city; the ‘great’ Heidegger was a Nazi; Lukacs was a communist; and J. P. Sartre wrote: ‘Any anti-communist is a dog.’”

“[When you write a play] you walk into a forest without a knife, without a compass. But . . . if you have a sense of geography, you find that you’re clearing a path and getting to the right place.”

“I wonder what these people thought thousands of years ago of these sparks they saw when they took off their woolen clothes?”

“When the Communist Party comes to power, it acts a lot like the mafia: If you are a loyal member in good standing, everything is yours. You're protected, even if you commit a crime.”

“There weren’t too many books by women that were taught in school, so I read those on my own, and the books I read were as accessible as the ones we were reading in school.”

“Fiction tells you, by the making up of truth, what really is true. That’s all fiction writers can do.”

“I've been accused of humanizing the Nazis, to which I can only say, you can't blame me for that. God did that. Go talk to him. It's a strange thing for an atheist to say.”

“Doom scenarios, even though they might be true, are not politically or psychologically effective. The first step . . . is to make us love the world rather than to make us fear for the end of the world.”

“Before you have the assumptions implicit in the first sentence, anything could happen. But once you have that sentence, you’ve narrowed your options down to a point where there really isn’t that much left to write.”

“[My fairy tale] is about moral responsibility—the responsibility you have in getting your wish not to cheat and step on other people's toes, because it rebounds.”

On Yeats’s assertion that one must choose between the life and the work: “Of course, if by life you mean life with other people, Yeats's dictum is true. Writing requires huge amounts of solitude.”

“I don’t know why, but I always feel a kind of necessity to write things that are beyond acceptance, that are too offensive or something. For people to read them and say, Ha-ha-ha, very funny. No, we can’t print that.”

“[My father] had brought in some large pieces of petrified wood . . . He said, “I reckon those things have been there since the Flood.” That Flood, of course, covered the whole earth, involved Noah’s ark, and presumably left petrified wood outside of Carrollton, Mississippi!”

“An English poet writes, I think, just for people who are interested in poetry. An American poet writes, and feels that everyone ought to appreciate this. Then he has a deep sense of grievance . . . ”

“What you have to do as a writer is write day in and day out no matter what happens.”

On his family: “Instead of expecting to make a big strike somewhere, which is a very American notion . . . I would have liked to see a little more just plain stick-to-itiveness at times. The longest journey begins with a single step . . . ”

“Writing to me is a deeply personal, even a secret function and when the product I turned loose it is cut off from me and I have no sense of its being mine. Consequently criticism doesn’t mean anything to me. As a disciplinary matter, it is too late.”

“Writing to me is a deeply personal, even a secret function and when the product I turned loose it is cut off from me and I have no sense of its being mine. Consequently criticism doesn’t mean anything to me. As a disciplinary matter, it is too late.”

“Bookishness, highest literacy, every technique of cultural propaganda and training not only can accompany bestiality and oppression and despotism but at certain points foster it.”

“In general, the food world … it’s just so against our nature.”

“God is this huge creature who we must know, love, and serve, though actually you feel like you want to kick the son of a bitch.”

“On Broadway, only the fire doors separate you from the sidewalk and you're lucky if the sound of a police car doesn't rip the envelope twice a night.”

“I don't really think it will make much difference to me when I'm dead whether I'm read or not . . . just as whether I'm dead or not won't mean much to me when I'm dead.”

Describing a doctoral thesis on Sophie’s Choice: “There was a footnote, which I swear to you said, ‘Where the movie is obscure I will refer to William Styron's novel for clarification.’”

On when he writes: “I like to stay up late at night and get drunk and sleep late. The afternoon is the only time I have left. ”

“Nonfiction writers are second-class citizens, the Ellis Island of literature. We just can’t quite get in. And yes, it pisses me off.”

“The thing that was magic about it was that once you put down one word, you could cross it out. . . . I put down mountain, then I'd go, no—valley. That's better.”

“I think trying to write is a religious exercise . . . When I create, when I put my own mark on something and form it, I begin to know the whole truth about it, how it was put together.”

“Who the fuck do you think wrote the Book of Revelation? A bunch of stone-sober clerics?”

“When I did the cartoon originally I meant the naked woman to be at the top of a flight of stairs, but I lost the sense of perspective and there she was stuck up there, naked, on a bookcase.”

“The thing about writing novels is that it must be a form of self-suppression. You don’t matter. The page is not a mirror.”

“Just as after you give birth you rapidly forget the pain involved, you easily overlook the effort that’s gone into composing a novel once it’s complete.”

“Any critic of Cezanne who described him as a painter of country scenes would be moving in the wrong direction. You must begin with the question of style . . . ”

On lending Mary Poppins to a friend who hated children’s books: “I got a letter back saying: ‘Why didn't you tell me? Mary Poppins with her cool green core of sex has me enthralled forever.’”

“English eccentricity has a suburban quality—it's like a very neatly trimmed garden in which you suddenly realize that the flower beds aren't what they seem to be.”

On first discovering his sense of humor: “I stood up with my right hand gradually becoming noticeably weird and said: ‘If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, may my right hand lose its cunning and my tongue cleave to duh woof of my mout.’”

“When I write, I aim in my mind not toward New York but toward a vague spot a little to the east of Kansas … ”