Issue 112, Winter 1989

The first interview session took place in July, 1984, as Kennedy was finishing a magazine piece about working on the screenplay for The Cotton Club. Kennedy talked for most of a Saturday afternoon at his home outside of Averill Park, a small community east of Albany and the Hudson River in a region of rolling hills where the landscape is sprinkled with picturesque lakes, meadows, and woods. A second interview was conducted in spring, 1988.

The Kennedys live in a handsome nineteenth-century farmhouse, a large white clapboard house with green trim and shutters, shaded and decorated on three sides by mature blue spruce, Norway spruce, and sugar maple trees. At the back of the house is a wooden deck, and across an expanse of lawn a swimming pool that was a sparkling invitation in the hot July sun on the day of the first interview session.

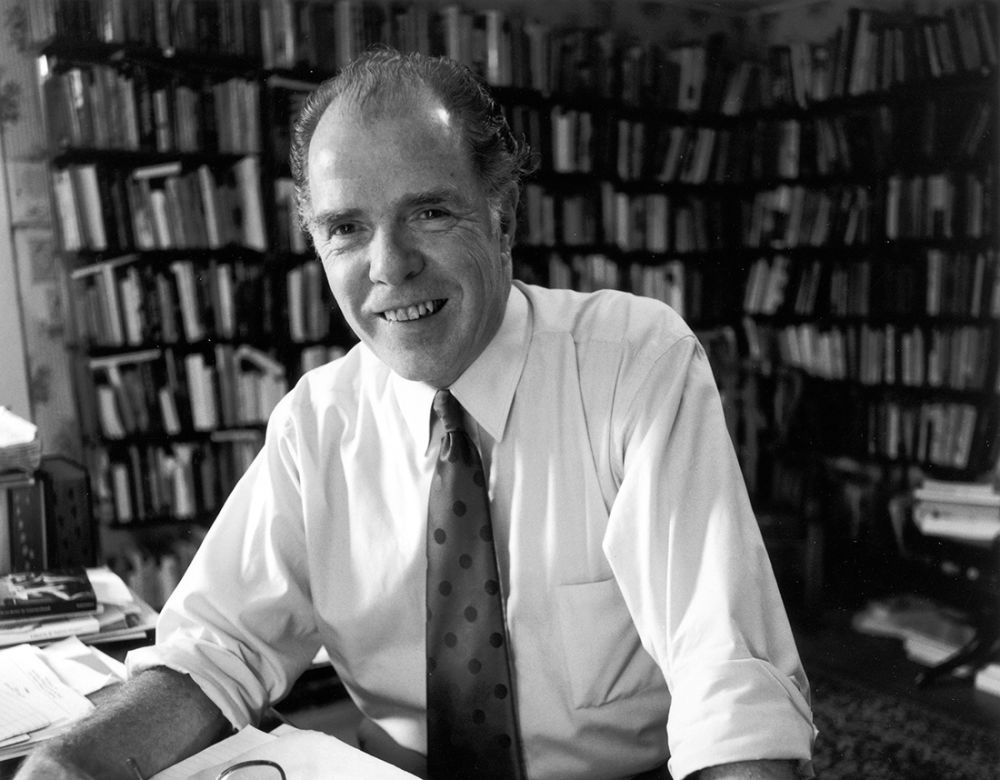

Kennedy, tall and fit, looking younger than his then fifty-seven years, in spite of the fact that his Irish red hair showed signs of thinning on top, appeared at the front door wearing a red-and-white striped sport shirt with rolled-up sleeves, white cotton pants, and white dress shoes. Born and bred in the city, a well-traveled, cosmopolitan man, he gave the clear impression of being very much at home in the country.

After a short excursion outside in the midday heat, Kennedy suggested that we go to his air-conditioned writing studio, a spacious corner room on the second floor.

Shelves of nonfiction works lined one side of the upstairs hallway, and his studio was filled from floor to ceiling with books against three of the walls: fiction, poetry, plays, and one large section of books on film and film criticism. A large wooden desk took up most of the space between two windows that looked out on the spruce and maple trees in the yard. Bookcases at each end of the desk were filled with reference books. The top of a cedar chest on the green shag rug was covered by more piles of books and papers, and nearby were boxes of letters Kennedy had received from his readers.

Collages of memorabilia decorated the back of the door to the hallway and the wall behind the desk: a poster of Francis Phelan from the cover of Ironweed; announcements of public readings Kennedy had given; a poster announcement of a reading by Saul Bellow at the Writers Institute; award plaques, and an honorary doctorate of letters; and photographs from Kennedy’s days as a newsman.

A straw hat with a black band hung from one of the curtain rods. It belonged to William Kennedy, Sr., who wore it in the 1920s. Another link to family and the past was Kennedy’s typewriter, set on a sturdy wooden leaf pulled out from the desk—a black L. C. Smith & Corona, 1934 vintage, that belonged to his mother, Mary Kennedy. Although he now uses a word processor for revisions, Kennedy still composes on this machine.

Kennedy sat at his desk in a wooden swivel chair that creaked slightly when he leaned back. Choosing his words with precision, he was often pensive with a serious, faraway look in his eyes as he talked of his life and his work.

INTERVIEWER

Can you explain the circumstances under which you got the MacArthur award?

WILLIAM KENNEDY

Well, in January I got a call from this man named Dr. Hope, and he asked me, was I William Kennedy, the writer, and I said I was. He said, “Congratulations, you have just been awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, which will give you $264,000 tax-free over the next five years.” I’d gotten a Chinese fortune cookie that week that said, “This is your lucky week.” I thought it had to do with the fact that I was getting reviewed in about five different major places in the same week. I thought that was good enough, but then I got the MacArthur. Quite a week!

INTERVIEWER

Is there any particular achievement to which they give recognition?

KENNEDY

They give it to you with no strings attached; they give it to all sorts of people—scientists, historians, translators, poets. Their first award to a writer that got widespread recognition was given to Robert Penn Warren. They give it to you on the basis of what you’ve done, but more important, I think, is their belief that you are going to do a lot more. It’s an award given with faith that the person is going to be productive. You don’t have to do anything for it; it just all of a sudden comes at you, like a health plan to cradle and protect you.

INTERVIEWER

Has the award changed your life?

KENNEDY

The change is that I have more options now to do things that have nothing to do with writing. Everybody wants me to become a fund-raiser or a public speaker or a teacher or go back to journalism or sit still and be interviewed. I’ve also become a correspondent. I’ve got something like a thousand letters, and the only thing I can do is try to answer some of them. Some I’ll never get to, but I keep trying. All this is very time-consuming. The fact is that it’s also very pleasant. I’m solvent, I can travel, I’ve been able to rewire the house, dig a new well, install a new furnace, put in a pool. Somebody accused me of going Hollywood in Averill Park, but that’s not accurate. I wanted a pool for twenty years. If I have a pool I’ll swim in it. If I don’t have a pool I won’t swim. And I don’t exercise. I don’t do anything . . . I never walk. I tend to dance at parties, which is a good way of having a heart attack if your feet still think you’re a nineteen-year-old jitterbug. The change has been very pleasant. People ask will I change the way I write, and I don’t believe I will. The work is based on what I see in the world, what’s around me and what I take home from that. It’s a superficial response if you change your writing because of a temporary change in your personal condition.

INTERVIEWER

Success came to you very late. Ironweed was turned down by thirteen publishing houses. How could a book that won the Pulitzer Prize be turned down by so many publishers?

KENNEDY

Yes. Thirteen rejections. Remember that character in “Li’l Abner,” Joe Btfsplk, who went around with a cloud over his head? Well, I was the Joe Btfsplk of modern literature for about two years. What happened was that I sold this book, then my editor left publishing; so that threw the ball game into extra innings. They gave me an editor in Georgia and I said, “I don’t want an editor in Georgia; I want an editor in New York.” They didn’t like that. She was a very good editor, but she only came to New York every two months. Georgia is even more remote from the center of literary activity than Albany. She was living on a pecan farm, as I recall. So that got the publisher’s nose out of joint. My agent was not very polite with them, and finally we separated. In the meantime, my first editor came back to publishing and, finding that Joe Btfsplk cloud hanging over my head, was not terribly enthusiastic about taking me back. So I went over to Henry Robbins, whom I had met at a cocktail party. Henry at that point was a very hot New York editor. He had just gone over to Dutton. Everybody was flocking to him. He was John Irving’s editor. Joyce Carol Oates moved over there. Doris Grumbach moved in; so did John Gregory Dunne. It looked like Dutton was about to become the Scribner’s of the new age. So anyway, at the cocktail party he said, “Can I see your book?” And I said, “Of course.” I sent it to him and he wrote me back this wonderful letter saying that he loved the idea of adding me to their list. I picked up the paper a week later and he had just dropped dead in the subway on his way to work. So I then went over to another publisher where a former editor of mine had been; she was somewhat enthusiastic, thought we might be able to make it if there were some changes in the book. And then she was let go. I bounced about nine more times. Then fate intervened in the form of an assignment for Esquire to do an interview with Saul Bellow—who had been a teacher of mine for a semester—in San Juan. He had really encouraged me at a very early age to become a writer. So he took it upon himself—I didn’t urge him, and I was very grateful to him for doing it—to write my former editor at Viking, saying that he didn’t think it was proper for his former publisher to let a writer like Kennedy go begging. Two days later I got a call from Viking saying that they wanted to publish Ironweedand what did I think of the possibility of publishing Legs and Billy Phelan again at the same time.

INTERVIEWER

It would seem that Bellow was the answer.

KENNEDY

I think he’s probably had several manuscripts sent to him since then. As have I.

INTERVIEWER

During this there must have been an immense amount of frustration. Did that experience give you ideas for changes that can or should be made in the publishing industry to encourage the writing of first-rate serious fiction?

KENNEDY

I don’t know what to do to change the world that way, except to generate a running sense of shame in their attitudes toward their own behavior so that the next time they might pay more serious attention to the work at hand. So much of the publishing world is run on the basis of marketplace success, and so when a book is rejected as a financial loser, it immediately has a cloud over it, especially if the writer is already established with one publishing house and this house chooses not to take his next novel. That carries a stigma; you’re like a leper. You go from house to house, and they say, well, Why didn’t so-and-so publish it? They published your last book. So you live under that cloud until you find some editor who understands the book and is willing to take a chance on it. I don’t know how to change human nature about this. I’m very pessimistic about it. I just see one good writer after another in deep trouble.

INTERVIEWER

So the difficulty in getting books like Ironweed published is not necessarily due to the lack of good editors at the major publishing houses, but might be more closely tied to the prevailing corporate policy you’re speaking of?

KENNEDY

I think there’s a casualness about the way things are read. I think subject matter tends to play a large part. If you have a novel of intrigue or romance, with adultery or exotic locale, or a spy thriller, you probably won’t have too much trouble getting published. If you have a major reputation, you’re not going to have any problem getting published. But it’s the writers who fall in the middle, who write serious books about subjects that are not the stuff of mass marketing, they have the problem—the so-called mid-list phenomenon. If the publishers don’t think it’s going to sell past a certain amount of copies, then they’re not interested. And I would think that that was the case with Ironweed. People had decided it was a depressing book, set in the Depression, about a bum, a loser, a very downbeat subject. Who wants to read a book about bums? So they chose not to accept it. Yet it’s not a downbeat book. It’s a book about family, about redemption and perseverance, it’s a book about love, faded violence, and any number of things. It’s about the Irish, it’s about the church.

So, again, I don’t see how you’re going to change the way editors think. They can’t contravene the commercial element in their publishing house. They’re as good as the books they bring in, and if those books don’t make money, what good are the editors? Very sad.