Issue 127, Summer 1993

War Music, Christopher Logue’s adaptation of books sixteen to nineteen of Homer’s Iliad, was published in 1987 and immediately hailed as a masterpiece on both sides of the Atlantic. It was the culmination of a long, sustained effort that produced Patrocleia (book sixteen) and Pax (book nineteen) in 1962 and 1969 respectively. For the past three years he has been working on books one to four, the first two of which were published last year by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in a single volume under the title Kings.

Logue’s account of the Iliad has been described as one of the major achievements of postwar English poetry, the most important translation since Ezra Pound’s “Homage to Sextus Propertius.” George Steiner has called it “a work of genius . . . the most magnificent act of translation going on in the English language at the moment,” while Louis MacNeice praised it as “not a translation but a remarkable achievement of empathy,” and Henry Miller exclaimed, “I’m crazy about it. Haven’t seen such poetry in ages.”

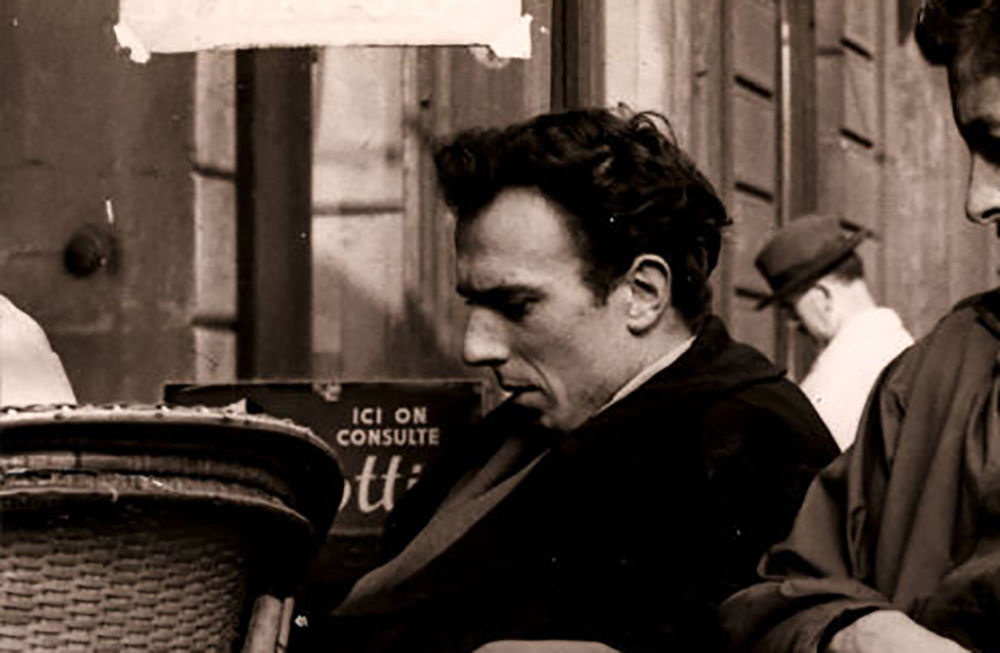

Christopher Logue was born in 1926 in Portsmouth, England and was educated at Prior Park College, Bath and Portsmouth Grammar School. At seventeen he volunteered for the Army, and in 1946 he was sent to Palestine, where he was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment for the illegal possession of government property. On his release in 1948 he returned to England and lived with his parents on public assistance before moving to Paris in 1951.

His first book of poems, Wand and Quadrant, was published in 1953 by Collection Merlin in Paris. Three years later A. A. M. Stols of the Hague published Devil, Maggot and Son. He moved back to London in 1958, and in the years that followed he went on to produce poetry, translations of Villon and Neruda, plays, film scripts, songs, and sketches. He has been a contributor to the satirical magazine Private Eye since 1960, and has published two collections from his column “True Stories” in books of the same title.

He lives with his journalist wife, Rosemary Hill, in Camberwell Grove, South London, and works in a quiet office at the top of the house. It overlooks on the street side one of the finest rows of Georgian houses in London and on the garden side the church of St. Giles, whose elegant spire rises over the trees and the low garden wall. He speaks in a deep, distinctive voice with a clear, melodious diction.

INTERVIEWER

A critic once remarked that your Iliad is the work of your genius, while your own poetry is the product of your talent. Let’s start with the latter. When did you become aware of your talent for poetry? What triggered it?

CHRISTOPHER LOGUE

My elocution mistress, Miss Crowe. As a child I had a deep voice. People would comment. My mother wanted me to be a priest or an actor, but seeing that there wasn’t much chance of the priesthood, she plumped for acting and sent me for elocution lessons. Miss Crowe was an attractive woman. I used to sit on the floor and look up her skirt—and that’s how I became a poet. She taught me how to scan, and introduced me to many good poets: Browning, Tennyson, Bridges, Kipling. My next contact with poetry was when I went to Priory Park, a Catholic boarding school located in a beautiful Palladian house built by Ralph Allen, a friend of Alexander Pope. On its grounds was a grotto built by Allen for Pope. I used to go and play there, although it was by then a dank, derelict place. I had no idea who Pope was.

INTERVIEWER

How about English? Were you good at it?

LOGUE

Yes. We did Shakespeare’s Henry V, and I loved it. I memorized chunks of it. People often say that their school put them off Shakespeare for life. That is nonsense. They had no taste for it and are ashamed of that, so they blame the school, the teacher, or the poet.

INTERVIEWER

What made you decide to go into the army instead of art school or university?

LOGUE

It was 1944. I was seventeen and a half and I couldn’t see my way forward. I had no idea what to do with myself. I was always in trouble. I was a trouble to myself. I thought maybe I’ll be killed, that’s the best thing for me.

INTERVIEWER

What kind of trouble did you get into?

LOGUE

Stealing. Money from my mother’s purse, or my father’s pockets, things from shops—semipornographic magazines, expensive toys, and sweets—and then I would be caught and punished. Once I was taken to a juvenile court. When the time came for me to appear, my father came with me with his retirement certificate—he was a civil servant, working in the post office for forty-five years—wrapped in brown paper under his arm. He unwrapped it and showed it to the magistrates. I felt incredibly proud of him, and terribly ashamed of myself. Thereafter I stopped stealing . . . except lines of poetry.

Anyway, the army took me in because there was a war and I was a volunteer. By the time I had finished my training, the war in Germany was over and my unit was sent to Palestine. We, the British, were trying to stop large-scale Jewish immigration into Palestine—this was 1946. I was there for three months before I went to jail.

INTERVIEWER

How did that happen?

LOGUE

How is easy to tell, why is hard to know. I think now that I contrived a way of getting the army to punish me. It was an act of spiteful masochism. I had by chance, but illegally, obtained six army paybooks, which were also identity documents. I announced to everyone in my tent that I planned to sell them to the Jews. I knew no Jews. I hardly knew what the word Jewmeant. But I identified with those my side was against. I imagined myself as a Jew. It was provocative. You must remember that at this time British soldiers were being shot by Israeli terrorists who might have used army paybooks to gain access to a camp. I took the paybooks with me into Haifa, but no sooner had I reached the town than one of the men to whom I had announced my plan arrived with an officer and arrested me. I pleaded guilty to the charges and I said, If I had had guns I would have sold them too. They gave me two years, with eight months remission, and I served sixteen months.

INTERVIEWER

Where was the prison? What was it like being a prisoner?

LOGUE

It was Acre, now Akko, a Turkish fort built on the site of a castle taken by Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade. I was put in with the Jewish prisoners because they were “white”—which meant European—under what was called Special Treatment, which was lucky for me, because the Palestinians were very badly treated, not physically, but like second-rate people, heaped up in crowded cells.

The governor of the prison was also the hangman, and when Jewish terrorists were to be hanged, he would hang them, and then come and inspect us. The condemned cell was close to our tower; we knew what was going on. Ours was one of four towers around the courtyard. I was in a tiny cell of my own with a view of the sea. I had books.

INTERVIEWER

Just the place for a budding poet. Did you have many books?

LOGUE

I used the prison library. I read continually but unsystematically. While under arrest before my trial, one of my fellow soldiers gave me the American edition of Auden’s Collected Poems. As well, I had a complete Shakespeare and the collected works of Oscar Wilde.