Issue 229, Summer 2019

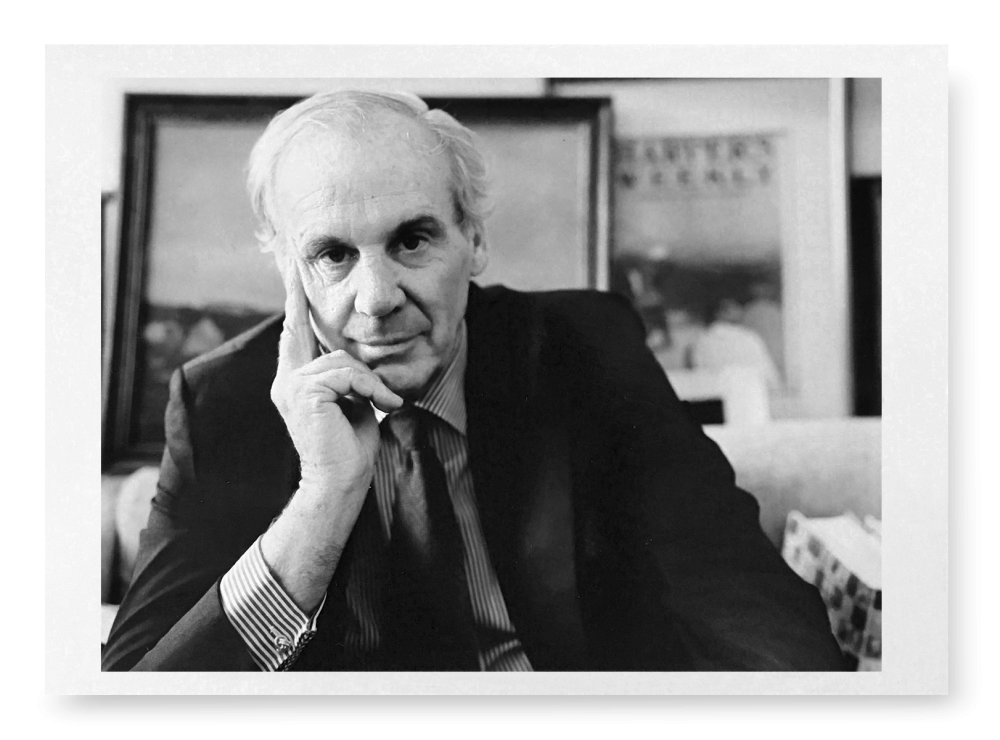

Photo by Matthew Septimus, courtesy of Harper's Magazine.

Photo by Matthew Septimus, courtesy of Harper's Magazine.

It is dangerous to excel at two different things. You run the risk of being underappreciated in one or the other; think of Michelangelo as a poet, of Michael Jordan as a baseball player. This is a trap that Lewis Lapham has largely avoided. For the past half century, he has been getting pretty much equal esteem in a pair of distinct roles: editor and essayist. As an editor, he is hailed for his three-decade career at the helm of Harper’s, America’s second-oldest magazine, which he reinvigorated in 1983; and then, as an encore a decade ago, for Lapham’s Quarterly, a wholly new kind of periodical in his own intellectual image. As an essayist, he was called “without a doubt our greatest satirist” by Kurt Vonnegut.

By the time I arrived in New York in the late seventies, Lapham was established in the city’s editorial elite, up there with William Shawn at The New Yorker and Barbara Epstein and Bob Silvers at The New York Review of Books. He was a glamorous fixture at literary parties and a regular at Elaine’s. In 1988, he raised plutocratic hackles by publishing Money and Class in America, a mordant indictment of our obsession with wealth. For a brief but glorious couple of years, he hosted a literary chat show on public TV called Bookmark, trading repartee with guests such as Joyce Carol Oates, Gore Vidal, Alison Lurie, and Edward Said. All the while, a new issue of Harper’s would hit the newsstands every month, with a lead essay by Lapham that couched his erudite observations on American society and politics in Augustan prose.

Today Lapham is the rare surviving eminence from that literary world. But he has managed to keep a handsome bit of it alive—so I observed when I went to interview him last summer in the offices of Lapham’s, a book-filled, crepuscular warren on a high floor of an old building just off Union Square. There he presides over a compact but bustling editorial operation, with an improbably youthful crew of subeditors. One LQ intern, who had also done stints at other magazines, told me that Lapham was singular among top editors for the personal attention he showed to each member of his staff.

Our conversation took place over several sessions, each around ninety minutes. Despite the heat, he was always impeccably attired: well-tailored blue blazer, silk tie, cuff links, and elegant loafers with no socks. He speaks in a relaxed baritone, punctuated by an occasional cough of almost orchestral resonance—a product, perhaps, of the Parliaments he is always dashing outside to smoke. The frequency with which he chuckles attests to a vision of life that is essentially comic, in which the most pervasive evils are folly and pretension.

I was familiar with such aspects of the Lapham persona. But what surprised me was his candid revelation of the struggle and self-doubt that lay behind what I had imagined to be his effortlessness. Those essays, so coolly modulated and intellectually assured, are the outcome of a creative process filled with arduous redrafting, rejiggering, revision, and last-minute amendment in the teeth of the printing press. And it is a creative process that always begins—as it did with his model, Montaigne—not with a dogmatic axiom to be unpacked but in a state of skeptical self-questioning: What do I really know? If there a unifying core to Lapham’s dual career as an editor and an essayist, that may be it.

—Jim Holt

INTERVIEWER

You started your career with the San Francisco Examiner.

LEWIS LAPHAM

My reasons for going into the newspaper business were twofold. One, to learn how to write. When you’re young you tend to use too many adverbs and adjectives, to think every word you come up with deserves to be engraved in marble. I hoped to cure myself of the habit acquired while writing papers at school and college.

The other reason was to get an education. Having grown up in Pacific Heights in San Francisco and then gone to prep school in Lakeville, Connecticut, and to Yale College, I knew I’d been living in a privileged, safe space and didn’t know much of anything about the rest of the country. Didn’t know how the politics worked, where the water came from, how the garbage was collected, who was living on the wrong side of the tracks. As a newspaper reporter, I expected to learn who were my fellow citizens, where and what was the American democracy.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s back up. Your grandfather was the mayor of San Francisco when you were a boy.

LAPHAM

Also a shipowner, the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company. Intercoastal trade. The ship would start with dry cargo in Seattle, go down the West Coast, through the Canal, around the Gulf, up the East Coast to Portland, Maine, and then back on reversed compass bearings. A very profitable business before the interstate highway system. On December 7, 1941, we owned a substantial fleet of ships. In early 1942, the United States government commandeered all of them for the North Atlantic convoys. Most of them were sunk by German U-boats. If I remember the story correctly, we were never reimbursed for the loss.

INTERVIEWER

As a boy, what were your passions? You must have read widely.

LAPHAM

Books were my boyhood. I can remember my mother reading Moby-Dick to me when I was six years old. Each evening I had to know exactly where the story had left off the night before or she wouldn’t read the next page. So I learned to stay with it. My father had a large library, he was himself a constant reader.

INTERVIEWER

And a writer, too. He was a columnist for the paper, right?

LAPHAM

Had been, yes. My father came back to San Francisco after graduating from Yale in 1931 to work for the Examiner, on occasion speaking directly to William Randolph Hearst, then enthroned at San Simeon. Under pressure from my grandfather, my father gave up journalism to become president of the family company.

And then my grandfather was elected mayor in 1942. He sometimes would go out to meet the aircraft carriers coming in from the war in the Pacific, take me with him in the launch, bring me up to the bridge to meet an admiral. When I was ten years old I wanted to become a navy carrier pilot. At Yale I didn’t qualify for the naval reserves because I was color blind.

INTERVIEWER

So what did you do?

LAPHAM

I was also in love with words. I tried my hand at poetry at Yale, and later at Cambridge in England, attempted to write in imitation of Yeats, Auden, Donne, Shakespeare, and A. E. Housman.

INTERVIEWER

The poetry you wrote back then, it scanned?

LAPHAM

It did. At Yale I discovered classical music and that also was an influence.

INTERVIEWER

You were already trained as a pianist?

LAPHAM

No. The house in San Francisco offered a fine view of the bay, but it wasn’t furnished with a piano. My parents listened on the Victrola to Cole Porter, Fred Astaire, and the Great American Songbook. At Yale I met Beethoven, Bach, Handel, and Mozart.

INTERVIEWER

Who was the first composer that moved you?

LAPHAM

My first lessons were on the harpsichord because I wanted to play Bach.

INTERVIEWER

So when you went on to Cambridge, you had an amateur interest in music and keyboard. You were there to study history.

LAPHAM

Medieval English history. At Magdalene College, I met C. S. Lewis, who had just come over from Oxford. I met Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Admired the poetry of Robert Graves, wrote him letters in Majorca. He didn’t write back.

At Cambridge, I was never in any kind of inner circle. I wandered around, audited lectures, wrote poetry, acted in plays. It was a lovely year, but I understood at the end of it I was not a scholar. I didn’t have the patience for footnotes. My parents were unwilling to fund my further education unless I was going to make an academic career.

So I went to Washington in the fall of 1957 and applied for work at the CIA, the White House, and the Washington Post. I didn’t pass muster at any of the three gates, ended up at the Examiner. I started on the police beat, moved up to city-desk general assignment. I was good at it.

INTERVIEWER

Good at writing on deadline and turning out clean prose?

LAPHAM

Well, yes. You had to be. But then I was fired.

INTERVIEWER

What was the cause?

LAPHAM

The weekly Sunday supplements for the Los Angeles Examiner and the San Francisco Examiner were both printed in Bakersfield. On that particular Sunday, in December 1959, the printers had made a mistake. The headline on the San Francisco supplement read “Los Angeles: Athens of the West,” with a twelve-page spread of photographs advertising the Southern California presence of Thomas Mann and Béla Bartók, Igor Stravinsky, Raymond Chandler, Aldous Huxley, and Christopher Isherwood.

When I got to the office at ten that Sunday, the paper’s publisher, Sunday editor, city editor, and managing editor were in a state of acute crisis. I figured a cruise ship had gone down in the bay, thousands dead and washing ashore at Fisherman’s Wharf. The city editor handed me the offending pages, denounced them as anathema, gave me until four o’clock in the afternoon to refute the treasonous fake news. The clarification was marked for page 1 and an eight-column headline in the Monday paper. I was to spare no expense of adjectives.

The task was hopeless. The cultural enterprise in San Francisco amounted to little more than Herb Caen’s gossip column promoting the city’s cable cars and views of the Golden Gate Bridge. The Beat generation had disbanded. Allen Ginsberg was still to be seen in the City Lights bookshop with Lawrence Ferlinghetti, but Kerouac had left town, and so had the Merry Pranksters. Evan Connell was in Sausalito, Wallace Stegner was at Stanford, Henry Miller at Big Sur. The theater was road shows from New York, the opera was second-rate, and so was the symphony orchestra. An hour before deadline, I informed the city editor that if there was such a thing as an Athens of the West, it probably was to be found on a back lot at Paramount. The chief slumped into an awful and incredulous silence, then rose from behind his desk to say I had betrayed the city of my birth, committed the sin of checking a good story for facts. Never could I expect to make good in the newspaper business.

I went to New York in January 1960, found work on the Herald Tribune. I considered myself the luckiest young man in the world. I thought the Trib the best paper in America, better than the Times because it was better written and with a sense of humor. Red Smith was the sports columnist, Irita Bradford Van Doren was the books editor, Joseph Alsop was handling the wisdom from Washington.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about the sixties.

LAPHAM

Journalism in January 1960 was not yet glamorous.

I can remember going to a cocktail party on the Upper East Side, and one of the fashionable young ladies present asked, What do you do for a living? I was proud to say I was a newspaperman. I couldn’t think of any more idealistic or romantic a calling. The young woman looked at me with faint amusement and disdain, said, What are you going to do when you grow up?

The attitude changed once Kennedy was elected president. At the Examiner, I had been the only Ivy League kid in the building. The advent of Kennedy brought a swarm of Ivy League swells into journalism with the idea that they were morally, intellectually, and socially superior to politicians. And what happens to journalism in the sixties is it becomes increasingly about the journalist. The so-called New Journalism was strenuously self-glorifying.

INTERVIEWER

And you’re doing straight reporting at this point.

LAPHAM

I’m always doing straight reporting. After I left the Trib, my writing for the Saturday Evening Post between 1963 and 1968 was straight reporting. The editors wanted a piece about LBJ in the spring of 1965, sent me to Washington to see if the Johnson White House resembled Kennedy’s Camelot, told me to stay as long as it took, paid for a suite at the Hay-Adams hotel. As a temporary member of the White House press corps, I walked across Lafayette Park every morning for two months to attend briefings, watch LBJ scratch his balls and his dogs. I took notes of what was to be seen and heard in plain sight.

INTERVIEWER

So you were not at all tempted by the stylistic experiments of Wolfe and Talese and Mailer?

>LAPHAM

No, I wasn’t. The story was good enough, in and of itself, if you stuck around and paid close attention.

At the Tribune I became close friends with Charles Portis, who in 1961 was a young reporter come to New York from Arkansas. Our desks were next to each other, and so were our attitudes toward the New Journalism. Neither of us tried to turn journalism into literature. Portis left the Tribune to go back to Arkansas to write True Grit. In 1968 I took two years off from the Post and tried to write a novel. For the day and age I was paid an outrageously generous advance. I rented a house for a winter in eastern Long Island and then a house in Jamaica for another six months. I put the manuscript through, I believe, eight drafts.

INTERVIEWER

Did you have a working title?

LAPHAM

No. The novel kept going from bad to worse. But I got lucky. I finally had to turn the thing in because I’d taken the advance. And literally the day I brought in the typescript, the book publisher, New American Library, collapsed. I never had to repay the advance, and the novel never got published. Thank god.

INTERVIEWER

And the manuscript went into your dresser drawer, and there it remains.

LAPHAM

There it remains.

INTERVIEWER

When you were at the Post you were working with one of the great editors, Otto Friedrich.

LAPHAM

I admired him more unreservedly than anyone else I met in Grub Street. He was the editor of the Post, also the author of fourteen very fine books. He taught me how to be an editor, how to be a writer.

INTERVIEWER

You were almost exclusively a writer at this point. How did he teach you to be an editor?

LAPHAM

My ambition was to hand Otto a manuscript that would pass into print without a mark on it in his blue pencil. A vain hope.

INTERVIEWER

But an admirable one.

LAPHAM

Otto would give back the manuscript marked up in the most helpful way. He would say, You can find a better word for this. You can compress this paragraph into a sentence. Throw these other three paragraphs into the wastebasket. I would sometimes spend two weeks writing the first page of ornate, lapidary prose. Otto would draw a line through the entire page, say, The article begins here on page three with the story.

In the winter of 1964, Otto began assigning pieces that took me out of New York for two or three months on the road, which put an end to my study of the piano. While working for the Tribune, I was used to practicing for three hours a night, studying with an old-world teacher, trained in Berlin, and prepared to drop me as a student if I missed a lesson two weeks in a row. Otto understood what I would be giving up, and by way of an apology, he assigned me to write about the jazz pianist Thelonious Monk, who was performing in New York that winter at the Five Spot Café. Knowing I admired Monk’s music, and that Monk was an enigmatic figure and hard to approach, Otto suggested I hang around listening to the music, if necessary for three months, at the Five Spot until Monk decided to talk.

INTERVIEWER

Did you disclose immediately that you were writing about him?

LAPHAM

Yes. And he said, Most people get me wrong, think I’m some kind of weird zombie of bop. And I said I’d try to tell the story straight with no chaser. About three months into it—by that time he knew I was studying Bach, working on Beethoven—Monk dropped by the table at four in the morning and said, Time to hear you play.

We went back to his apartment on Eleventh Avenue in a chauffeured Rolls-Royce owned by the baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a patroness of jazz musicians in whose Fifth Avenue apartment Charlie Parker had died. Monk’s apartment was littered with children’s toys and kitchen pots—an extremely domestic scene, in no way zombie bop. Monk had a baby grand backed up against the bathroom door. He took off his hat and sat on the can to listen to me play. His wife, Nellie, and the baroness sat on the one couch in the room. I played Beethoven, opus 90, a sonata in two movements. E minor. To my surprise, I didn’t miss a note.

Monk came out of the bathroom, looked at me straight in the eyes and said, I heard you. Maybe the remark was ironic, or he meant I actually had some music in my soul. I decided on the latter interpretation, figured that my debut was also my final performance, decided to quit while I was ahead. And then I got married, and my wife couldn’t bear the thought of my practicing three hours a night.

INTERVIEWER

Did she want you to spend time going to dinner parties?

LAPHAM

No. She wasn’t interested in the New York society program.

INTERVIEWER

But you would go to Elaine’s.

LAPHAM

In the sixties I was traveling so much, all over the world for both the Post and Life, and spending only six months a year in New York. Half the fun of the traveling abroad was the coming back to tell the story at Elaine’s, a restaurant and bar on East Eighty-Eighth Street that attracted a crowd of journalists and miscellaneous show-business people. There were two tables reserved for friends of the management, forty or fifty people who never had to worry about finding a place to sit. One table for the after-midnight poker game, the other for literary and political gossip. I spent most of my time in the card game, learned I was not a gambler. A lot of my life has been learning what I’m not.

INTERVIEWER

You were already Lewis Lapham at that point. A well-known figure.

LAPHAM

Well known at Elaine’s, not well known anywhere else. In ’69 the Post went out of business. I signed a contract with Life to do the same kind of long-form reporting. And then Life goes down, and I’m out of work. I meet Willie Morris one night in Elaine’s and sell him the idea of a story about Alaska. Willie is the editor of Harper’s Magazine at this point. Oil had just been discovered on the North Slope, and I offered to spend the whole winter in Juneau to see what the politicians would do with a $900 million windfall—suddenly having all that private money in public hands, they had a chance to make good on all the fine-sounding promises about providing decent government. They didn’t. I wrote one other piece for Harper’s—about the New York Stock Exchange, which was then being taken over by computers—which I delivered in early 1971, and it’s at that point that Willie left.

INTERVIEWER

Under pressure from the owners.

LAPHAM

I had only been in the office twice—in 1970 to deliver the manuscript from Alaska, and then again to deliver the manuscript on Wall Street. As a contributing editor I was being paid five thousand dollars an article, which was still a lot of money in those days.

INTERVIEWER

It’s become a lot of money again now in journalism. And all those magazines were not doing well back then. As you pointed out, Life had gone out of existence, the Saturday Evening Post—

LAPHAM

Television killed them all. Television in the sixties changed the magazine business model because television was not paying any distribution cost. It’s the same thing with print now being moved online.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about Willie’s departure.

LAPHAM

Willie had been the editor since 1967, two years after the Minneapolis Star and Tribune Company acquired a controlling interest in the magazine from the book publisher Harper & Row. He changed the tone and point of view of the magazine established by his predecessor, Jack Fischer. Fischer had come of age as a newspaperman in Texas and Oklahoma in the thirties, served in the OSS in London during World War II. His old-school notion of the republic of letters favored the reasoned essay and straight reporting. He deplored what he regarded as the moralizing solipsism of the New Journalism, made it a rule never to publish Norman Mailer.

Willie made it a rule to publish Mailer. His magazine was a success with the New York literary crowd, a failure with a majority of its readers and subscribers. In 1971, John Cowles, chairman of the Star and Tribune Company, asked Willie to reconfigure the magazine in ways that might recover at least some of its lost circulation. Willie refused to even consider the proposition. He resigned, believing Cowles wouldn’t dare accept the resignation of a celebrity too important to be tampered with. A mistake. When Cowles didn’t bow to Willie’s nonnegotiable demands, Willie’s coterie of contributing writers and in-house editors resigned in symbolic protest. They resolved to force the magazine out of business, show that without them it didn’t exist. I told Cowles that if he meant to continue financing the magazine I would do what I could to help edit it. It was an accident that I become an editor.

INTERVIEWER

You had no fears about taking on an entirely new set of responsibilities? Were you confident you could be effective as de facto managing editor?

LAPHAM

No. I thought the job was going to be temporary. I thought Cowles was clearly going to find a new editor, probably Otto Friedrich, still the best editor in New York, who had moved to Time after the Saturday Evening Post folded. I expected to hold the fort for two or three months and then go back to writing. Jack Fischer came out of retirement, came down from Connecticut two days a week to teach me the fundamentals, show me how to do this, how to do that.

INTERVIEWER

Which of the fundamentals was the hardest to learn? Some came easy, some came hard?

LAPHAM

The hard thing was learning to play straight with a writer. Tell him or her right away if you weren’t going to accept the article. Don’t let the decision hang around, don’t blame the decision on some sort of committee.

INTERVIEWER

That’s a rare virtue in an editor. There’s a lot of unnecessary torture that editors inflict on writers.

LAPHAM

Also I had to learn to make constructive suggestions. It’s not good enough to say, I don’t like this. Show how the mistakes can be fixed. Usually what people had trouble with was structure. They didn’t know how to get off on the right foot, how or where to find their own voices. Also, most of the manuscripts were apt to be much too long.

INTERVIEWER

Were you doing the nitty-gritty stuff?

LAPHAM

Sometimes I would.

INTERVIEWER

You’d actually have a blue pencil?

LAPHAM

Fischer used to rewrite a lot of manuscripts. Sometimes I did the same.

INTERVIEWER

Did you enjoy doing that or did you find it onerous?

LAPHAM

I found it to be fun. It was like giving me another voice. But I’d only do that if I saw exactly what had to be done and it was okay with the author.

When it came to assigning pieces, I’d look for a topic that interested the writer, one the writer wanted to pursue. What was wanted was a topic useful for the magazine, but, more importantly, one that excited the writer.

INTERVIEWER

What was the first piece you brought in that you were really thrilled to have in the magazine, the one that set the tone for how Harper’s would be in the Lapham era?

LAPHAM

It was a piece by Annie Dillard. There was, for a very brief moment, a Harper’s Magazine Press that published books. An agent, Blanche Gregory, sent a manuscript written by “A. Dillard,” no indication of gender. It was a fragment of a book, a chapter of what became Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. I said, Blanche, I’d like to buy this for the magazine, and I’ll pay fifteen hundred dollars if I get the right to buy the book for the Harper’s Magazine Press. The book won the Pulitzer Prize.

INTERVIEWER

This is the beginning of what proved to be a very long tenure. You arrived at Harper’s as an editor in 1971 and you were there until 2006. Not quite as long as Silvers and Epstein at The New York Review of Books or Shawn at The New Yorker, but the same kind of geologic time. At the start of that, there had been a big exodus of the old crowd, after Morris left, and you were having to find new writers, which probably wasn’t hard, but maybe it was.

LAPHAM

It wasn’t, but then of course I was fired in 1981.

INTERVIEWER

This was when the MacArthur Foundation stepped in and bought it for a dollar and made it a nonprofit.

LAPHAM

Well, not quite. What happened was that Cowles in 1979 decided to sell the magazine. And I said, John, supposing I can put together a group to buy it. He said he already was in touch with the likely, big-money prospects—

Hearst, the Washington Post, Reader’s Digest, et cetera—but he gave me permission to look for alternatives. The magazine at that point was losing something like $1 million a year, interest rates hovering somewhere around 18 percent, but Cowles expected a price of $4 million. He found no takers. I had an offer from the Twentieth Century Fund—one-dollar purchase price, assumption of the magazine’s debt. Cowles rejected the offer, preferring to fold the magazine and reap the reward of a substantial tax deduction. He served notice of the magazine’s extinction in June 1980, front-page story in the New York Times.

INTERVIEWER

Were you distraught at the possibility that it was going to fold? Were you so existentially invested that you wanted to save it at all costs? Or were you maybe enjoying the idea that you would be liberated from this deskbound existence?

LAPHAM

I wanted to try to save it. And I had a month to do so before the magazine missed an issue. Agents were asking for manuscripts back, everybody on the staff left except Sheila Berger, the art director, who was married to Tom Wolfe.

INTERVIEWER

So it was just you and Sheila.

LAPHAM

Yes, and then I receive a phone call from John “Rick” MacArthur, twenty-four-year-old reporter for the Chicago Sun-Times, also the grandson of the founder of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. I didn’t know Rick, never had met him. He admired my writing in the magazine, thought it a worthwhile voice in the wilderness. Before the month was up, he persuaded the foundation’s board to keep Harper’s Magazine in business. For the next six months I was both editor and publisher. Then the MacArthur Foundation appointed a separate board to run the affairs of the magazine, and in August 1981, the new board dispensed with my services. They objected to my writing a column for the magazine that struck them as unnecessarily critical of the American dream.

INTERVIEWER

Then there’s the weird interval in which Michael Kinsley is the editor.

LAPHAM

I really don’t know how that worked. I only met Kinsley once. He didn’t like New York at all. There was a plan afoot to have The New Republic take over Harper’s, put them both in the same building in Washington.

INTERVIEWER

But still be separate titles?

LAPHAM

I didn’t know but assumed so. I had been told that Harold Hayes was to be the new editor, an outcome I looked forward to. Hayes had been editor of Esquire, next to Friedrich the best editor in New York. He asked me to stay with Harper’s as a writer.

INTERVIEWER

A nice prospect for you.

LAPHAM

It was. But then Harold demanded a high-rolling budget to reinvigorate the magazine, and the board withdrew its offer of the editorship. I moved to a small windowless room in the MetLife Building for two years, wrote a weekly column for the Washington Post, gave occasional—very occasional—speeches.

INTERVIEWER

That must have been a pleasant two years for you.

LAPHAM

They weren’t, but then in 1983, Rick MacArthur got himself elected to the Harper’s Magazine board of directors and invited me back into the game. I accepted on two conditions. One, I get to completely redesign the magazine. Two, everyone who was on the board that fired me be themselves fired. To my surprise, both of the conditions were met.

INTERVIEWER

You redesigned the magazine right away, with the Harper’s Index, the Readings section, and the Annotation. What were the other aspects of the redesign?

LAPHAM

Short texts and lists of possibly significant numbers anticipated the sensibility soon to appear on the internet. The web didn’t exist. The blog and the emoji not yet known as forms or figures of speech. The design was like the old Atlantic. Nine or ten longish articles in every issue, a self-defeating format. Take any five magazines and between all five of them they’re lucky to come up with ten first-rate articles over the course of a whole year. The Harper’s redesign allowed for one well-reported piece and one well-thought-out essay. I wasn’t forced to fill space. I could work on both manuscripts.

INTERVIEWER

But it’s a risky strategy, because you end up having a bum issue if either the essay or the reported piece isn’t good, and that’s inevitably going to happen.

LAPHAM

Not if you pick wisely with the Readings section and give yourself enough time to work with the authors of the major pieces.

INTERVIEWER

And you sustained this template from 1984 to 2006. During that entire two-decade period, Harper’s looked pretty much the same. And it still does look like that.

LAPHAM

They’ve been messing around with the cover design, but the interior remains as it was.

INTERVIEWER

During that period everyone had to know what was in each issue of Harper’s. When writers appeared into Harper’s, suddenly their stock was way up in the literary world, they were much more popular at Paris Review parties.

LAPHAM

Over the period of 1984 to 2006 it was my great good fortune to publish a long list of truly talented writers, among them Evan Connell, Otto Friedrich, Eduardo Galeano, Edward Hoagland, Richard Rodriguez, Barbara Ehrenreich, Christopher Hitchens, Veronica Geng, Henry Fairlie, Paul Fussell, Marilynne Robinson. Also, the first pieces to appear in print by a number of other writers soon to become prominent. Dillard at the beginning, but also Barry Lopez, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Donovan Hohn, Matthew Power, and David Foster Wallace.

INTERVIEWER

Wallace’s account of his disastrous experience on a cruise ship—that was in Harper’s.

LAPHAM

Yes, but the first commissioned piece he wrote for the magazine was about tennis. He was invited to do so by Charis Conn, our brilliant senior editor also responsible for the Harper’s Index. She knew how to make the juxtapositions of numbers count. She really had a feeling for the idea, turned it into an art form.

INTERVIEWER

Those juxtapositions you’d find each month in the Harper’s Index were very powerful. Very funny, very telling.

LAPHAM

Charis was wonderful. I was always lucky in the people I had working with me. Michael Pollan was a marvelous editor. He started as the editor of the Readings section, then became executive editor. Then Ben Metcalf, a magnificent editor, during my last twenty years. Others too numerous to mention. John Leonard was the book critic. No better book critic ever walked the face of the earth.

INTERVIEWER

That’s interesting, because in my mind, Leonard’s style is very, very different from yours, almost the antithesis.

LAPHAM

So what. He was a wonderful writer. I had the chance to write my own essay in every issue, had no reason to impose my style and thought on any other writer.

INTERVIEWER

Walk us through the rhythm of a monthly column.

LAPHAM

After I knew what else was going in the magazine, I’d try to fill in the blanks. If what was in the issue was mostly political, I would write something cultural. If the issue was more cultural, I’d write something political. I’d ask myself Montaigne’s question, What do I know? Which usually was not much. What I knew about Reagan or Clinton was what I could read in the newspapers, and having been a reporter I knew how little that really amounted to. As I went on with the column, more and more often I’d try to bring the perspective of the past to bear on the present. The longer I stayed at Harper’s, the more I got into reading books instead of newspapers. I stopped reading Time and Newsweek in the late eighties. I never acquired the habit of watching television news. When dealing with current events, I tried to stay with what I had actually seen for myself, not what I had been told by a reliably informed source. My object in writing the essay was to learn, not preach, which is why I never was inducted into the college of pundits.

INTERVIEWER

As a practical matter, you began the column in the last week of the preparation of the monthly issue, so you had a week to do it and you had to figure out what you think in a Montaignesque way, and you also had to get the cadence and the meter right and balance all the clauses and find the right metaphors. It seems almost impossible to me.

LAPHAM

Well, it wasn’t a week, it was two weeks. I started two weeks ahead of time and then I took liberties. I sat next to the copy editor and made final changes as it got closer to going to press. Balzac went bankrupt with what are called AAs—author’s alterations. If you’ve ever seen a Balzac manuscript, it’s completely overwritten with ink. He keeps sending it back to the printer. That was the droit du seigneur I enjoyed at Harper’s. I’d make changes down to the very last moment.

INTERVIEWER

In 2008, when you wrote your valedictory column under the rubric of the Notebook, you said that this process never got any easier.

LAPHAM

No, it didn’t.

INTERVIEWER

But you couldn’t live without doing it. The essay is your form.

LAPHAM

It becomes a pleasure after about the fifth, possibly the sixth draft. At that point it begins to be fun because you begin to have an inkling of what you’re trying to say. You never know what you think until you try to set it up in a sentence, maybe fish it into the net of a metaphor. The writing doesn’t get easier, but the work becomes play.

INTERVIEWER

In a piece I wrote for the Times Book Review on Sir Thomas Browne, I said that the history of English prose is that of a dialectical struggle between two tendencies, the plain tendency and the grand or mandarin. And I gave a list of the exemplars of each. The plain included Dryden, Swift, Didion. The mandarin began with the King James Bible and Edward Gibbon, and concluded with Lewis Lapham. Are you happy to be in that mandarin company?

LAPHAM

Yes, I am. When I was at college I was an admirer of both Sir Thomas Browne and Gibbon. I modeled my attempts at poetry on Auden, but I modeled my prose on Gibbon, Joseph Conrad, and Browne.

INTERVIEWER

Conrad? That’s an odd choice.

LAPHAM

He is a magnificent writer. He knows how to write sentences.

INTERVIEWER

That’s true. You described what a powerful influence Otto Friedrich, as your editor, was on helping you repress some of your more baroque tendencies. But you still retain this delight in more elaborate or even ornamental prose.

LAPHAM

Yes, I do. But as I get older I’m cutting some of that back.

INTERVIEWER

I’ve noticed that. Late Lapham is not like late Henry James.

LAPHAM

No, it gets simpler. Instead of more ornate.

INTERVIEWER

Is that deliberate? Do you find the more ornate prose distasteful?

LAPHAM

Superfluous.

INTERVIEWER

Adjectives and adverbs are out?

LAPHAM

Always under suspicion. To describe a woman as fabulous is to say she is nowhere to be seen.

INTERVIEWER

Not necessarily fewer subordinate clauses, though. You’re in a high percentile when it comes to deploying those. More Gibbonesque than most writers today.

LAPHAM

I still permit myself the longer sentence, but I’m more careful about making sure that every word counts. And I’m learning to balance them with short sentences. I’m also having more fun because I’m beyond the point where critical opinion one way or the other is going to do me any harm or any good.

INTERVIEWER

At what stage does the fun come in? For me, it’s only looking back on the piece after I’ve written it.

LAPHAM

I write a lot of drafts. As I said, the fun of it for me is when I get to the fifth or sixth draft. Then I can play with possibilities. The first draft is like breaking rocks.

INTERVIEWER

But the structure of it, the architecture of it is set early. The later drafts are about embellishing that.

LAPHAM

Unfortunately, no. Sometimes you completely change direction. Sometimes you get to the end of the third draft and understand it’s nonsense. An essay is a very risky form. It’s like getting out there on a high wire. It’s easy to fall off.

INTERVIEWER

Are you ever surprised by the conclusions you’re led to?

LAPHAM

Always.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve referred to Lapham’s Quarterly as your masterpiece. Is this in some sense the consummation of your career?

LAPHAM

I started out in life wanting to become a historian, and after Yale and Cambridge I went into the newspaper business, then the magazine business. But I never lost my interest in history. As I wrote essays for Harper’s Magazine, every month for thirty years I never knew what I’d find until it showed up on the page. Writing an essay is an adventure, a lighting out for the territories.

INTERVIEWER

Are you suggesting there’s something of that quality to Lapham’s Quarterly?

LAPHAM

Yes. That’s exactly what the Quarterly becomes. If you remember Montaigne, Montaigne is constantly asking questions. He’s talking to Seneca, he’s talking to Cicero. Testing what he knows against what they have seen and said. Let me put it this way. Gibbon rates history as little more than the register of mankind’s follies, crimes, and misfortunes. The observation falls well short of the mark. History is the vast store of human consciousness adrift in the gulf of time, the present living in the past and the past living in the present. So when I read Shakespeare, Jefferson, Twain, or Machiavelli, I’m with them in time present. It’s why we still read Edith Wharton, Virginia Woolf, James Baldwin, and Flaubert—what survives the wreck of time is the force of the imagination and the power of expression. And that is as alive and well today as it was two hundred or two thousand years ago. So the Quarterly essentially is set up as a historical essay, the same way Montaigne set up his essays. Harry Truman once said that the only thing that’s new in the world is the history you don’t know. There’s also truth in Faulkner, who said that the past is never dead—it’s not even past. So I think we have more to learn from reading Diderot, Henry Adams, and Martin Luther King Jr. on government and democracy, on what is meant by a republic, than by reading all but a few of our contemporary magi.

INTERVIEWER

But the contemporary voices are also in the Quarterly.

LAPHAM

That’s what history is. It’s a conversation between the past and the present.

INTERVIEWER

Arthur Schlesinger was fond of quoting the Dutch historian Pieter Geyl, who said history is an endless argument.

LAPHAM

Schlesinger wrote an essay for the New York Times a few weeks before he died in 2007 at the age of eighty-nine, entitled “Folly’s Antidote.” And that was his idea of history. It’s what saves us, the knowledge and sense of history, what saves us from the delusions of omniscience and omnipotence, from misplaced faith in money and machines. The internet works against historical consciousness because the new and newer news comes so quickly to hand that it buries all thought of what happened yesterday or the day before in an avalanche of data. The more data we possess, the less we know what it means. You know the trends. The schools and colleges aren’t teaching history very much anymore. Even the better colleges promote the stem curriculum. Our languages today, most of them are being made by and for machines. We have machines to arrange the trades for Tinder and Goldman Sachs, to scan the flesh and track the blood, cue the ATM and the GPS. Machines that tell us where to go, what to do and think. The machines cannot hack into the enormous store of human consciousness because they don’t know what the words mean. Yes, Alexa and Watson can access the Library of Congress, but they can’t read the books. The past living in the present and the present living in the past is the stuff of which dreams, and Lapham’s Quarterly, are made.