Issue 246, Winter 2023

Beijing Normal University, 2021. All photographs courtesy of Yu Hua.

Beijing Normal University, 2021. All photographs courtesy of Yu Hua.

Yu Hua was born in 1960. He grew up in Haiyan County in the Zhejiang province of eastern China, at the height of the Cultural Revolution. His parents were both in the medical profession—his father a surgeon, his mother a nurse—and Yu would often sneak into the hospital where they worked, sometimes napping on the nearby morgue’s cool concrete slabs on hot summer days. As a young man, he worked as a dentist for several years and began writing short fiction that drew upon his early exposure to sickness and violence. His landmark stories of the eighties, including “On the Road at Eighteen,” established him, alongside Mo Yan, Su Tong, Ge Fei, Ma Yuan, and Can Xue, as one of the leading voices of China’s avant-garde literary movement.

In the nineties, Yu Hua turned to long-form fiction, publishing a string of realist novels that merged elements of his early absurdist style with expansive, emotionally fulsome storytelling. Cries in the Drizzle (1992, translation 2007), To Live (1993, 2003), and Chronicle of a Blood Merchant (1995, 2003) marked a new engagement with the upheavals of twentieth-century Chinese history. To Live—which narrates the nearly unimaginable personal loss and suffering of the Chinese Civil War, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution through the tragic figure of the wealthy scion turned peasant farmer Fugui—brought him his most significant audience to date, its success bolstered by Zhang Yimou’s award-winning film adaptation.

Once an edgy experimentalist adored by college students, Yu Hua is now one of China’s best-selling writers. Each new novel has been an event: Brothers (2005–2006, 2009) is a sprawling black comedy satirizing the political chaos of the Cultural Revolution and the unbridled consumerism and greed of the economic reform era under Deng Xiaoping; the magic realist farce The Seventh Day (2013, 2015) is narrated by a man wandering the living world after his death; and his most recent, Wen cheng (The lost city, 2021), reaches back to the late days of the Qing dynasty. He is also one of the country’s best-known public intellectuals, having authored nonfiction books on topics including Western classical music, his creative process, and Chinese culture and politics. His New York Times column, which ran from 2013 to 2014, and China in Ten Words (2010, 2011) have been heralded as some of the most insightful writings on contemporary Chinese society.

More than a quarter century ago, I, then a college senior, reached out to Yu Hua to seek permission to translate To Live into English. Our initial correspondences were via fax machine, and I can still remember the excitement I felt when I received the message agreeing to let me work on his novel. We later exchanged letters, then emails; these days, we communicate almost exclusively on the ubiquitous Chinese “everything app,” WeChat.

Our first face-to-face meeting was in New York, around 1998. It was Yu Hua’s first trip to the city, and he responded to the neon lights in Times Square, attending his first Broadway show, and visiting a jazz club in the West Village with almost childlike excitement. He exuded a playfulness, a sharp wit, and an irreverent attitude that I found startling. Could this exuberant tourist really be the same person who wrote the harrowing To Live? Apparently so.

Our interviews for The Paris Review were conducted over Zoom earlier this year. I saw glimpses of the same quick humor, biting sarcasm, and disarming honesty I remembered from our time together twenty-five years before, but with new layers of wisdom and reflection.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about being a dentist. How did that come about?

YU HUA

I’d finished high school in 1977, just after the end of the Cultural Revolution, when university entrance exams had been reinstated. I failed, twice, and the third year, there was English on the test, so I had no hope of passing. I gave up and went straight into pulling teeth. At the time, jobs were allocated by the state, and they had me take after my parents, who both worked in our county hospital. I did it for five years, treating mostly farmers.

INTERVIEWER

Did you like it?

YU

Oh, I truly disliked it. We had an eight-hour workday, and you could only take Sundays off. At training school, they had us memorize the veins, the muscles—but there was no reason to know any of that. You really don’t have to know much to pull teeth.

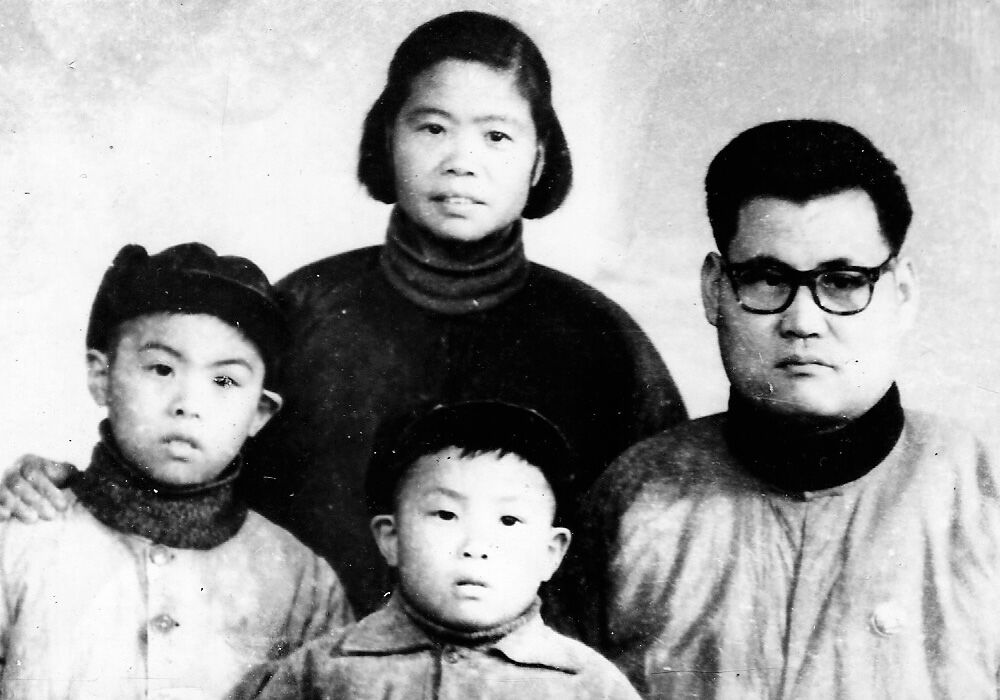

At center, with his parents and older brother, ca. 1966.

At center, with his parents and older brother, ca. 1966.

INTERVIEWER

When did you start writing short stories?

YU

In 1981 or 1982. I found myself envying people who worked for what we called the cultural center and spent all day loafing around on the streets. I would ask them, “How come you don’t have to go to work?” and they would say, “Being out here is our work.” I thought, This must be the job for me.

Transferring from the dental hospital was quite difficult, bureaucratically—you had to go through a health bureau, a cultural bureau, and, in the middle, a personnel bureau—but then, of course, there was the even more pressing issue of providing proof that I was qualified. Everyone working there could compose music, paint, or do something else creative, but those things seemed too difficult. There was only one option that looked relatively easy—learning how to write stories. I’d heard that if you’d published one, you could be transferred.

INTERVIEWER

Was it as easy as you’d hoped?

YU

I distinctly remember that writing my first story was extremely painful. I was twenty-one or twenty-two but barely knew how to break a paragraph, where to put a quotation mark. In school, most of our writing practice had been copying denunciations out of the newspaper—the only exercise that was guaranteed to be safe, because if you wrote something yourself and said the wrong thing, then what? You might’ve been labeled a counterrevolutionary.

On top of that, I could write only at night, and I was living in a one-room house on the edge of my parents’ lot, next to a small river. The winter in Haiyan was very cold, and back then there weren’t any bathrooms in people’s houses—you’d have to walk five, six minutes to find a public toilet. Fortunately, when everyone else was asleep, I could run down to the water by myself and pee into the river. Still, by the time I was too tired to keep writing, both my feet would be numb and my left hand would be freezing. When I rubbed my hands together, it felt like they belonged to two different people—one living and the other dead.

INTERVIEWER

How did you learn how to tell a story?

YU

Yasunari Kawabata was my first teacher. I subscribed to two excellent magazines, Beijing’s Shijie wenxue (World literature) and Shanghai’s Waiguo wenyi (Foreign art and literature), and I ended up discovering many writers that way, and a lot of nineteenth- and twentieth-century Japanese literature. By then we had a small bookstore in Haiyan, and I would order books almost blindly. One day, I came across a quote by Bernard Berenson, about The Old Man and the Sea and how “every real work of art exhales symbols and allegories”—that’s how I knew, when I saw Hemingway’s name in the store’s catalogue, to ask for a copy.

At the time, when books went out of print the Chinese publishing houses usually just wouldn’t put out any more, so you never knew, when you saw a copy of something, if you’d have another chance. I remember persuading a friend who ended up going into the real estate business to swap me Kafka’s Selected Stories for War and Peace—he calculated that it was a good deal to get four times the amount of book for the price of one. I read “A Country Doctor” first. The horses in the story appear out of nowhere, come when the doctor says come and leave when he says go. Oh, to summon something and have it appear, to send it away and have it vanish—Kafka taught me that kind of freedom.

But my earliest stories were about the life and the world that I knew, and they haven’t been collected, because I’ve always thought of them as juvenilia. When I first started writing, I had to lay one of those magazines down beside me on the table—otherwise I wouldn’t have known how to do it. My first story was bad, hopeless, but there were one or two lines that I thought I’d written, actually, quite well. I was astonished, really, to find myself capable of producing such good sentences. That was enough to give me the confidence to keep going. The second was more successful—it had a narrative, a complete arc. In the third, I found that there wasn’t just a story but the beginnings of characters. That story—“Diyi sushe” (Dormitory no. 1), about sharing a room with four or five other dentists training at Ningbo Hospital No. 2—I sent out, and it became my first publication, in a magazine called Xi Hu (West Lake), in 1983. The next year, I was transferred to the cultural center.

INTERVIEWER

Did you find it easy to get published?

YU

I had good luck. During the Cultural Revolution, there’d been no real literary magazines in China—there was one in Shanghai, Zhaoxia (Clouds of dawn), that sort of qualified, though it was all very politically correct—but afterward, the old journals started publishing again, and new ones were founded. Even in Haiyan we had little kiosks that sold nothing but literary magazines, and there was a period from 1978 to 1984 or so when they didn’t have enough work by established writers to fill their pages. That created a wonderful environment where editors took unsolicited submissions very seriously—the one good story they found would get passed around the entire staff.

By 1985, it was different—it became very difficult to get published if you didn’t have a connection, especially if you were considered “avant-garde.” I remember going back to one of these magazine’s offices, sitting around and chatting with some editors, and seeing a hill of submissions piled in the corner, ready for whoever took the trash out to remove them. I realized that if I’d taken another two or three years to start writing, I’d still be a dentist.