Issue 218, Fall 2016

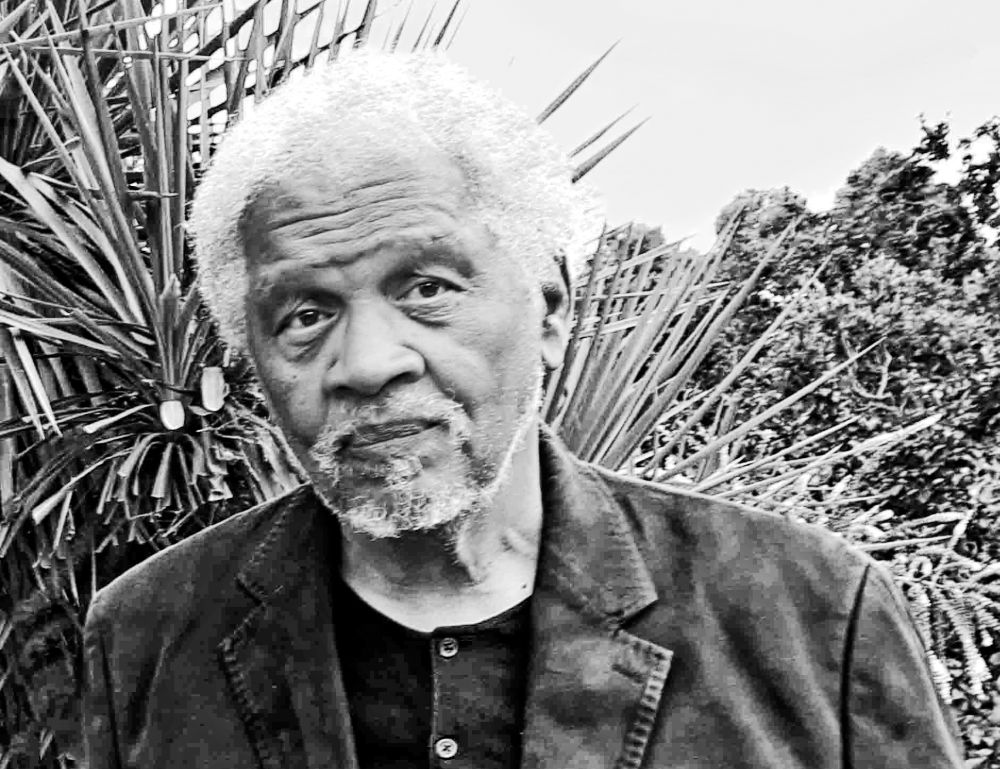

Reed, 2015. “Combative Writing has always been our tradition, even when we try to avoid it.”

Reed, 2015. “Combative Writing has always been our tradition, even when we try to avoid it.”

I met Ishmael Reed at the Bowery Hotel, in New York, where he was staying for a couple of nights with his wife, the dancer and educator Carla Blank, and his daughter, the poet Tennessee Reed. In the novel Mumbo Jumbo (1972), Reed’s most acclaimed work, black artists spread “Jes Grew,” a virus of freedom and polytheism and improvised expression that overthrows a repressive status quo. Reed, gray hair swept to the side, eyes constantly darting around, restless with ideas and mischief, has become Jes Grew personified. His own groundbreaking literary output over six decades, in multiple languages and every form—essays, fiction, poetry, film, even editorial cartoons—has infected a generation of artists. His work as an institution builder, anthologist, and publisher has spread the work of hundreds of writers from outside the literary mainstream—students, black folks, immigrants, working-class writers, avant-garde experimentalists, and every member of his immediate family. Tennessee and Carla are both published authors, as is Timothy, Reed’s elder daughter. Reed’s late mother, too, wrote a memoir, called Black Girl from Tannery Flats.

Reed’s present trip to New York, from his home base in Oakland, was a quick stopover on his way to Venice, where he was to receive the Alberto Dubito International Prize for his poetry. In his acceptance speech for the award, he would talk movingly about the tradition of black writing, “the kind of writing that I called ‘writing is fighting,’ a term that I borrowed from the boxer Muhammad Ali,” and of his hero Dante, another fighting writer who paid a price for his iconoclasm. The award was a reminder that poetry, as a form and sensibility, is the thread woven through everything he’s produced, from blues lyrics and a gospel opera to his collage-like fiction.

Despite his deep generosity and his pioneering work in defining an inclusive American aesthetic, Reed’s literary combativeness over the years—his clashes with certain feminist critics are the best known, but his list of targets and antagonists is long—has made him, in his words, a writer in exile. When I walked into his hotel room, the mood was quickly set by the bright, bickering figures on his television screen—a cable-news program on Donald Trump. Reed sat in a darker corner of the room shaking his head at the farcical scene and allowing a deep, sly laugh. Over the hours we talked, I occasionally tried to steer the conversation to questions of style and technique, but Reed parried those questions and instead returned, again and again, to politics, history, the fate of America and the world, and his battle fronts, still raging.

—Chris Jackson

INTERVIEWER

Let’s start with something elementary. What is the first poem you remember reading?

REED

You know, I didn’t really start reading poetry until I started going to the University of Buffalo, where I spent two and a half years. Before that, I spent a semester in the night-school division of the university, Millard Fillmore College. I may have read T. S. Eliot, maybe some of the modernists. I read some Langston Hughes in the newspapers. The Simple series. I read some things in high school, routine stuff—Edgar Allan Poe and all that. They didn’t introduce us to a single black author. But I really didn’t start reading poetry until I started at the university. The university was like a trade school for me. Matter of fact, I stayed too long, because within two years I had all the tools necessary to make a modest income as a writer.

INTERVIEWER

Did you enter university thinking that that was what you wanted to do, to be a writer?

REED

When I went to grammar school in Buffalo, I got mostly negative reviews from the white women teachers—these teachers would say such terrible things about my behavior that I was ashamed to take their report cards home. I had only one black teacher during my whole education, a woman named Hortense Butts. She encouraged me and gave me tickets to concerts. Called upon me to play Christmas carols on the violin. I used to get beaten up by black women and white women. I was an equal-opportunity target. In first grade, I was slapped so hard by one white teacher my mother took me out of school. In eighth grade, I was assaulted by a woman teacher. She had a Victorian style. It was because I had a fistfight with her teacher’s pet, who called me a rat in front of the class. I thought to myself, How do I gain this woman’s affection? Because I wanted to be liked. That was my whole thing. I was someone who wanted people to like me—I still am.

INTERVIEWER

And how did you win her favor?

REED

She told me that the greatest thing in the world for me would be to be a tech man. She told me I should go to the technical high school. So I did. I was totally unequipped. I got Fs. We had a thing in woodshop where the first assignment was to make a box to put your tools in—I never got beyond that. I spent most of the time in the band room playing the trombone and the violin.

INTERVIEWER

Did you ever get the box done?

REED

No, I didn’t, because I was afraid of those electric saws. So I transferred to a traditional high school, and that year I went on a trip to Paris, sponsored by the Michigan Avenue Y in Buffalo, for a Bible-study thing. That trip changed my life.

INTERVIEWER

How?

REED

On the plane to Paris, I read in this guidebook that there was a place in Paris called Pigalle where you could see “acres and acres of breasts.” A few days later, that’s exactly where I went and before the day was over I was at a table with a big old bottle of champagne in front me—me and a couple of hip white boys from Long Island. And we woke up there the next morning, too, at that same table. In Paris, I met Africans for the first time. All I knew of Africa before was what I’d seen in the movies and the textbooks here in the United States, but these Africans were students and intellectuals studying at the Sorbonne. I thought, I have been lied to. Not one had a bone in his nose. I think that was when I began to challenge everything I was being taught. One day, one of my high school teachers asked me to be part of a delegation that was going to meet Eleanor Roosevelt. I said, No, because I’m not going to be here. What can you all teach me? I had been in Paris, man, wearing my fake glasses and talking about existentialism, even though I was mispronouncing the word. When I came back to Buffalo, I dropped out of school. I was seventeen. My plan was to stay home and read plays but my mother said, You’ve got to get a job, so I worked at a library and that’s where I first read James Baldwin. I think it was Notes of a Native Son. It stopped me cold. I had never seen a black guy that could do this. When I was a child, I thought literature was written by lords and knights and stuff. You know, these people living in these great estates wearing beautiful clothes. Baldwin showed me something different. Then I discovered Dante, man. That really turned me on. My parents thought I had lost my mind. I would go up to the attic of our house in Buffalo and play a recording of John Ciardi’s Inferno while I followed along with the book. I read Dante and realized how much power a writer could have. A writer could put people in hell who weren’t even dead yet. I loved James Joyce, too, and really studied his work—at the library I would listen to proceedings of the James Joyce Society. I especially loved Dubliners. Nathanael West was another favorite, A Cool Million. I had never seen satire and nonlinear writing like West did—he was creating collages—and that influenced me. I still write that way. I wrote a short story in night school that was a mix of Joyce and Nathanael West. My teacher responded very strongly to the story, and they offered me a full scholarship to day school at the University of Buffalo. I didn’t receive the full scholarship because my stepfather wouldn’t sign a statement of his assets.

INTERVIEWER

Why not?

REED

“These white folks want to know all my business.” I liked my stepfather, I loved him. But there was just a gap between us. He was semiliterate and grew up in the South. Southern blacks were always getting finagled out of their assets by con artists. This still happens. Since 1979 I’ve lived in Oakland’s inner city, where we’re bombarded by mail and phone by predators who want to lure us into shady transactions. Anyway, I didn’t get the scholarship, but I didn’t really need it. I borrowed money to enter day school. After a year and a half, I had read Yeats, I had read Pound, and I had already read Joyce. I had studied enough to steer me to what I wanted to do in writing. My ideas for Neo-HooDooism were inspired by those Irish writers and their Celtic Revival. I discovered Pound’s ideas about multiculturalism, which influenced me, although I think I’ve gone beyond him because I’ve studied Japanese. I get my characters right. He didn’t. And he was a fascist, but I’m talking about his writing. Yeats’s anticolonial literature was another important discovery for me. What we ended up doing in the sixties was to revolt against the colonial masters. You see colonialism in the fifties generation of writers, in Baldwin, in Ellison. They talk about their masters and influences—Baldwin, who was a great writer, a great writer, always mentioned Henry James and Dickens. Ellison and those guys, they mention Hemingway. There was an abrupt departure from those sources in the sixties, when black writers start reflecting the influence of Malcolm X. And then we went off into all kinds of directions. Some black writers went into Arabic and African languages. I went into folklore, looking for examples of African religions surviving the slave trade. I called this Neo-HooDooism. Nobody told us about this but it was all right there, underground.

INTERVIEWER

So those writers gave you some ideas about drawing from alternative sources, but did they also help you think about your style on the page?

REED

Yes, and so did W. H. Auden. I still have that sort of spare style. I was also very much influenced by George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” where he advocated that you refrain from flamboyant language.