Issue 171, Fall 2004

© Catherine Wolff

© Catherine Wolff

This interview took place in the summer of 2003, at Tobias Wolff’s home in northern California. He had just returned from ten months in Rome, where he finished work on his eighth book, Old School. Standing by a wall adorned with family photographs, Wolff produced a galley of the novel, noting that the cover featured a photo of the dining hall at the Hill School, where Wolff had been a student. To get in, he forged his own letters of recommendation; two years later, he was asked to leave—for failing math and other crimes, among them “eating potato chips while leaning out the window.” In 1990, the Hill School granted him his degree (class of ’64), but only after the headmaster made sure to read a selection of Wolff’s fictitious letters of recommendation to that year’s commencement audience.

After school, Wolff briefly worked on a ship, and in 1964 volunteered for the army. Four years later, he was discharged. Oxford University came next, followed by stints as a reporter, a waiter, a night watchman, and a high-school teacher. In 1975, he was awarded a Wallace Stegner Fellowship by Stanford University, where he remained as a lecturer for two years. He taught in the creative writing program at Syracuse University from 1980–1997, after which he returned to Stanford, where he now holds the Ward W. and Priscilla B. Woods Professorship in the School of Humanities and Sciences. Widely considered a master of the short form, Wolff is the author of three books of stories: In the Garden of the North American Martyrs (1981); Back in the World (1985); and The Night in Question (1996). A novella, The Barracks Thief (1984), won the pen/Faulkner Award for Fiction; and his two memoirs, This Boy’s Life (1989), which won the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, and In Pharaoh’s Army: Memories of the Lost War (1994), a National Book Award finalist, are hailed as bench- marks of the form.

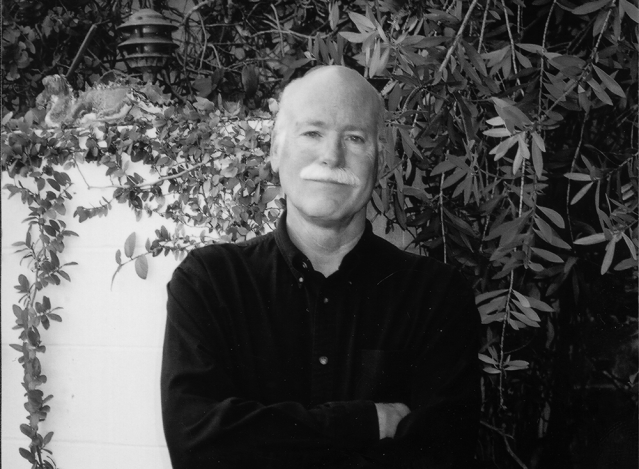

In person, Wolff is unassuming and possessed of a quiet authority. There is, of course, the mustache, which has gone white. And it’s hard not to notice the military crispness with which he crosses his legs, his snap-to-it posture and the athletic efficiency with which he moves. Even so, these vestiges of a military life are tempered by his supremely emotive face and his habit of peppering conversation with down-home colloquialisms like ain't it the truth.

Though a private man, Wolff is open about his nagging suspicion that his good fortune in life—his arrival at the age of fifty-eight with his family intact, a home in a warm climate, a place to write and teach, even a dog—is a fabrication that could burn to the ground at any moment. “I am lucky,” Wolff has said on many occasions, but there is resignation in his voice when he says it, a nod to the law of equal and opposite reactions. One might argue that Wolff’s rough childhood counterbalances his current success, but Wolff himself has never made such a claim, probably because to do so would be to submit to self-pity, an indulgence he doesn’t allow himself in his writing, and which appears to have no place in his life, either.

In conversation Wolff is quick to voice his exasperation with work he considers inauthentic, or with writers whose poses cast longer shadows than their books. All the same, during the interview he insisted that the tape recorder be turned off if he felt himself about to say something that might damage another writer's reputation. In most cases, his devastating comment would turn out not to be so devastating after all, but it is the curious mix of propriety and the writer's natural appetite for gossip that makes Wolff an engaging conversationalist. And although he didn't object to the inclusion of a story about Richard Yates (the as yet unpublished biography of the writer “would contain far worse,” he said), months later he continued to worry that it was somehow too explicit to be fair to Yates’ memory.

INTERVIEWER

Why don’t writers like to talk about what they’re working on?

TOBIAS WOLFF

Writers are superstitious. I don’t mean knock on wood, throw salt over the shoulder—let me try to explain. I began this whole writing enterprise with the idea that you go to work in the morning like a banker, then the work gets done. John Cheever used to tell how when he was a young man, living in New York with his wife, Mary, he’d put on his suit and hat every morning and get in the elevator with the other married men in his apartment building. These guys would all get out in the lobby but Cheever’d keep going down into the basement, where the super had let him set up a card table. It was so hot down there he had to strip to his underwear. So he’d sit in his boxers and write all morning, and at lunchtime he’d put his suit back on and take the elevator up with the other husbands—men used to come home for lunch in those days—and then he’d go back to the basement in his suit and strip down for the afternoon’s work. This was an important idea for me—that an artist was someone who worked, not some special being exempt from the claims of ordinary life.

But I have also learned that you can be patient and diligent and sometimes it just doesn’t strike sparks. After a while you begin to understand that writing well is not a promised reward for being virtuous. No, every time you do it you’re stepping off into darkness and hoping for some light. You can be faithful, work hard, not waste your talents in drink, and still not have it happen. That’s what makes writers nervous—the sense of the thing being given, day by day. You might have been writing good stories for years, then for some reason the stories aren’t so good. Anything that seems able to jinx you, to invite trouble, writers avoid. And one of the things that writers very quickly learn to avoid is talking their work away. Talking about your work hardens it prematurely, and weakens the charge. You need to keep a fluid sense of the work in hand—it has to be able to change almost without your being aware that it’s changing.

INTERVIEWER

So do you go to work every day like Cheever?

WOLFF

Generally I do.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write in the house?

WOLFF

No, I have a study in the basement of the university library. They offered me a nice place to work with a view of the Stanford hills, and I turned it down for this dump in the stacks because I’m so easily distracted. All I need is a window to not write. The only books I keep with me are a dictionary and some other reference books. If I have a good novel in the room with me, I’ll end up reading that. Writing’s hard. You’ll take any out, if you can. I work best away from the house because I’m too tempted to check for calls and my mail and deal with tradesmen and run an errand, go out for lunch.

INTERVIEWER

Serious writers don’t strike me as lazy—just the opposite, in fact. So why the compulsion to do anything but write?

WOLFF

I don’t know if that’s true for everybody. I hesitate to generalize. I’m sure there are writers who don’t feel that tug away from the desk.

INTERVIEWER

What’s your writing day like?

WOLFF

Boring, if you’re not me. I take a walk or go for a swim, then go to work, eat, take a walk, write, come home. I never go to movies about writers because writers lead very boring lives if they’re actually working. When I was a kid and saw these pictures of Hemingway on safari or fishing in Idaho, or Fitzgerald in Paris, I thought, What an exciting life writers must lead. What I didn’t know is that’s what they do when they’re not writing. What’s exciting is finding a word that’s been dodging you for days, or deciding to cut something you’ve spent weeks on. The excitement’s in the writing. It doesn’t offer much in the way of drama, I’m afraid. Routine becomes invaluable to writers, and that’s why once they hit their stride, their biographies make very poor material.

Think about the way other people work—lawyers, for example. They get up from their desk, they walk into the doorway of the office next door, and say, Hey, do you remember that Warthog v. Warthog case from two years ago? and they talk about it, and that’s work. They go out, meet clients and take depositions, they have meetings where they discuss strategies for pursuing a particular case—it’s a very social profession. I wonder how much of their time is actually spent dead alone, producing hard solitary thought for hours a day. That’s what writing is and in that way it’s very hard work and it absolutely requires all the conditions that make one a bore: You have to be alone a lot, you have to be rather sedentary, you have to be a creature of routine, you have to fetishize your solitude, and you have to become very, very selfish about your time.

INTERVIEWER

You’re just back from ten months in Rome. Why were you there?

WOLFF

I had no immediate reason for going. It wasn’t to do research. I speak some Italian, but living in a country where I can’t be completely aware of what people are saying around me puts this sort of bubble around the head, in which, for a time, not indefinitely, I find I’m able to work with more than the usual concentration and joy. I like not having a car, living in the center of a city where you can walk everywhere. All the errands that seem to consume one’s life become very few, and you find yourself with great stretches of time for reading, wandering, and yes, working. It was a good place to live for ten months, and I was dying to come home at the end of it. I finished the book I was writing and began to wonder why I was there, and when I begin to wonder why I’m somewhere, I know it’s time to come home, because I actually like being surrounded by my own language and knowing what’s going on around me. But it’s good for a while to be dropped through the bottom, to be a little helpless, to have to scramble to make do, because as you get older, you do less and less of that, and it’s good for you, it takes the rust off.

INTERVIEWER

So living abroad is in some way inspirational?

WOLFF

Not in the sense that I’ll necessarily write about the place I’m in—we spent a year in both Berlin and Mexico and I still haven’t set anything there. But just the breaking out, the newness of things, the having to struggle a bit, all that is bracing.