The night Coin Foreman was returned home from his wanderings, the Corinthian Baptist Church of Christ burned to the ground in a five alarm fire. Along Berriman Street the news was flashed from open window to open window by popped out heads and mouths and mouths working into the disaster gossip like fast scissors.

“Been burning now for close to three hours, say half the fire brigades of Brooklyn working on it…”

“And that ain’t all. They broadcasting for the evacuation for three blocks around.”

“Ohoooooowwwooooeee”

“Almost started to join that church but something told me, something said right out loud…”

“…and they’re calling on Manhattan to get to the rescue…”

“I knew something was gonna happen when them church collections was stolen…”

On the sidewalk Mrs. Fox and Mrs. Carth nodded together: chickens picking com. Coin thought as he watched

“It’s the vengeance of God on them,” panted Mrs. Carth.

“The insurance, I hope the insurance is paid,” answered Mrs. Fox.

The Richard sons and the Jeffers had stopped playing bridge and carried the news from group to group. They were flyer pigeons roosting on the far away siren calls and flying away to excite other air with news.

“They telephone me,” cried Mrs. Jeffers “that a dead body’s lying at the pulpit like a roast.”

“Oh great savior,” was all Mrs. Richardson could manage.

“Cyril,” yelled Mrs. Jeffers to her husband, “didn't I tell you about them cigarettes. Put that one out this minute.”

“Woman I been smoking since I was a child in Trinidad.”

Mrs. Jeffers was beside herself, “Cyril, I said put that damn cigarette out.”

The children had stopped playing catch and jumping-rope, and take-a-giant step. They begged to go to the fire of their lives. No parent said yes and a clamor went up.

Coin was hurried along by Miss Lucy Horwitz. They were chased down the street by the darkness in and out spotlight street lamps. The scissor talk made wounds in Coin’s aching head. He was safe now and at home and unhappy. His church was burning down, not the synagogue or St. Gabriel’s but his church. No one had greeted or recognized him or said I’m sorry Coin. Miss Horwitz had her hand nailed to his; she wasn’t going to take any chances that he’d run away again while he was with her.

“You’d better stay with me boy. We don’t want any more criminals in the family like your brother, Oscar. Well, they can shout their prayers in the gutters now for all I care. I only hope Agnes doesn't get too close to that heat. I told her not to go there tonight but oh no your father just dragged her along to that funeral as if she hasn’t had funerals enough.”

Mrs. Renaldo was coming toward them in her usual mourning clothes.

“Gracious here comes that Italian scarecrow. Let’s crossover.” Coin pulled back.

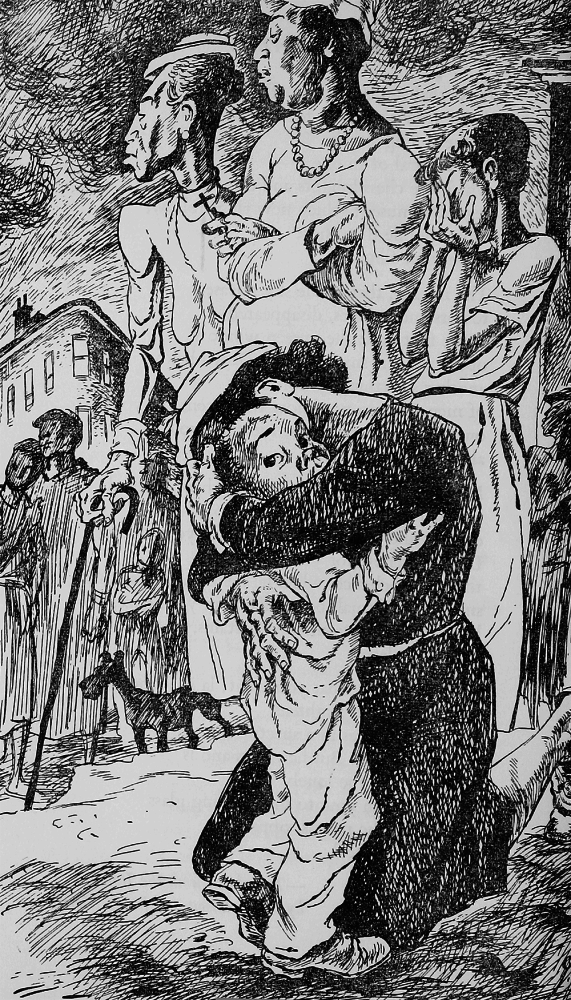

Mrs. Renaldo had already reached them with her half, dragging trot. She stumbled toward Coin with her love for him spread out in those arms. She hugged him away from Miss Horwitz: “O mio angelo, o mio angelo Coin. Where? Where? Where were you lost? I missed, I missed, I missed you everyday.”

Coin stayed in her arms. It was his first welcome home, even if she was rocking with chianti wine and dug her nails into his shoulder blades. Coin loved her. She had been hi smother’s friend. Miss Horwitz jerked him out of the clamping embrace. Now he was forced to go to the fire where he really wanted to go. But he wanted to stay, too, closed in those black sleeves of love.

During the short ride on the El, toward the scene of the fire. Miss Horwitz talked as always, sharp, as if she wanted to puncture the tire of a boy’s bike.

“That Mrs. Renaldo’s always hugging people. You’d better watch out Coin, one of these days you’ll get a disease. I hate people to be feeling of me anyhow.”

Coin was looking out of the window near Troy Avenue. He wasn’t studying her a bit; he was thinking of all the other rides he had taken along this same route with his brother Woody and his sister Berniece and his father chewing gum to disguise the cigar smell. He was thinking of the morning he became a Christian so that he could pray for his mother to get well and… He was thinking of the pennies he had stolen from the collection plate to spite God because his mother had died anyway. He had had his enemies and the chief one was God… he had started his revenge the Sunday after the funeral when the usher passed that old red velvet collection plate. And every time he took a penny out one of God’s white hairs fell. Old baldy headed God. So after a while he took to drinking lots of water. He wasn’t scared now about his sin because he had nothing to do with this fire. A year ago he would have wallowed in ashes like the Jews in their grief and atonement. He was a wanderer when it all started. It wasn’t his fire.

“Coin, are you listening to what I'm saying.?”

“Yes, Miss Horwitz.”

“What did I say just now?”

“I don’t know; it’s so hot in here I’d like to die.”

“Where’d you get that expression from? From some of your friends on the road?”

She made road and friends sound like they were the back-side of nothing. She bared her purple gums letting out the smell of old mayonnaise. Her hand was still nailed to his, the sweat between their palms was anchor glue. His “friends on the road.” After he had sneaked away from his blind Uncle Troy and his girl friend, Mrs. Walker who made his Uncle do dirty things in bed in Washington, D.C, he got on a train for Kentucky with his saved up money to find his only friend, Ferris. He didn’t even know Ferris’ last name but only that he lived in a town that began with the three letters MAD… and that in Ferris’ house was a golden synagogue chair. Ferris had said: “If you come visit me Coin you can take it back for your father to sit in.” And then Ferris had laughed his honeysuckle laugh, and continued, *“if you really came, I’d like to die.” He remembered that when he had entered that train for Ferris’ Kentucky every coach was crowded, loud with noise and funky. As he would pass through with his excuse-me’s people turned to stare at him with this greasy lunch bag and the tag on his chest:

COIN FOREMAN—TEN YEARS OLD

I am going to Madison, Kentucky—To be met by Ferris

In case of accident or death get in touch with Ferris

Nobody had bothered to read it, not even the lady at the ticket place. She had looked at it but didn’t bother to read. He had printed it nice, copying from the tag his sister Agnes had put on him when he first started for D.C. and changing it to suit himself. And he carried his map too. The one bought at Union Station Souvenier Counter. He had spread it out on a bench real smooth and found Kentucky way over there. How many mountains there were to cross, the rivers and cities, the lines on all the plains. And the criss-crossing lines. With his greasy bag. Mad–spelled Madison, his fat hope. He knew where he was going. But Ferris would be at the end. He was put in mind of the clown with the white face, red hearts painted on his cheeks and a smile painted on purple, a wig the color of carrots in his father’s backyard. This old clown danced on pulling at a peppermint rope. He pulled and he pulled for all he was worth and the rope never stopped coming, it kept on coming until the middle ring of the circus was filled with the candy colors… finally at the end there came a prancing juggler tossing golden balls with lights anthem. He kept seven going like magic. That’s how he knew it was going to be with him on the train; Ferris would be at the finish.

So he hadn’t minded the stares. He was bunked from side to side by the people and the movement of the train until he reached a last car where there was silence except for shifting feet and bags being thunked on overhead racks. Everyone here seemed to move around like in the silent movies and the train pushing toward Kentucky with buopola, buopola, buopola music. Wheels of music. He found a seat near a hot window and sat up tall for a while. In a minute he was slumped down and asleep. He woke up with a start. It was dark outside. Pebbles of summer rain beat against his window. For a moment he didn’t know where he was; at church weeping as he looked at his mother in the coffin; leading his blind Uncle Troy around Washington, D.C. or with Ferris gathering aggies from his golden garden in Kentucky. Then he felt as if he was stuffed in a bag of straw and couldn’t breathe. Then when he looked around he felt cross-eyed like the time he was first drunk in the JIM-JAM Cafe in D.C.. Next to him was a lump-of-dough man, fast asleep, working spit in the comers of his lips, one hand was between his legs resting on a long lump in his pants and the other was on Coin’s thigh. He dared not move. There were still wheels of music but the sound was slippery in the rain. A scream in his throat was like to explode in a fire engine sound, he smelled old mayonnaise. The man at his side shifted awake. He poked his tongue at Coin and conjured signals with his fingers into his face. Still there was no sound. Coin managed to put fingers into his ears to see how they were stopped up. He looked around afraid. He longed to vanish back into his crocus sack of straw. But he couldn’t get in again. When he looked around the whole car was filled to bursting with the people making their fingers in signs, pursing their lips, stretching their mouth sat each other, rolling their heads, scratching the air. The only sound was slippery in the rain. He was fully awake now. Suddenly it dawned on him that they were talking in semaphore. Giant puppet men. He doubted if he could ever speak again and he was afraid to try. The man next him rubbed Coin’s sweating head. Kept rubbing and bubbling with his mouth sliding back and forth on a harmonica of air. Coin managed to say a scared hello. But the man gestured more than ever. Once long ago when he couldn’t answer one of Miss Raidin’s questions in school, she asked him if he was deaf and dumb. Now he whispered as if he were dazed awake: yes Miss Raidin I’m deaf and dumb, I’m deaf and dumb, I’m deaf and dumb… bell. That did it. He could move now. He shook his head free of the scratching hand. They all looked toward him and he smiled and made little motions with his mouth and tried to talk with his hands. A carload of smiles turned in his direction. Soon he heard crackling paper and smelled food. He remembered his lunch clutched in his handy the window. As he started to open it a gentle hand toolkit from him and thrust a chicken leg at him and others came over with rolls or a piece of fruit or half a sandwich. They smiled and urged him to eat by eating themselves and pointing to the food they had offered. It was a different kind of picnic from the annual ones given by the Sunday school of the Corinthian Baptist Church on Bear Mountain but these faces around him were just as happy with him in the center. If Ferris was here it would be complete. He stuffed himself grinning around between fast bites, at his silent talking Santa Clauses.

When the conductor came around for the tickets Coin fished his out and waited. Maybe this was where he would be caught or asked questions he couldn’t answer. But with his friends on the car and the food peaceful inside him, he wasn’t afraid. Starting from the far end of the car he heard the bite of the puncher into tickets. He was almost last. The big human blue wall was beside him, examined his ticket, hi stag and then his face. Coin wiped at the grease around his mouth. The silent friends began to creep close making a circle when the conductor said, that he was sorry but Coin didn’t belong in this car.

“You belong in the first car sonny, near where the engines at.” And he started to lift Coin by his arm. What did he do that for? The circle closed in with the freak wavings, the harmonica playing mouths, the extra spit, the crazy semaphore; closed around the conductor and walked him toward the door. Blue wall stopped near the door. Everything else stopped too. Blue wall shot his arm out, pointed his finger, like a keystone traffic cop in the movies, directly at Coin.

“Sonny, I’m telling you, this car ain’t for colored!” He shut the door with a soft swish and was gone.

An arrow had been aimed at Coin and shot. The deaf and dumb were moving toward him to ease it out.

“Coin,” Miss Horwitz was saying, “have you lost your senses. Don’t you know where to get off after all these years?

Coin stumbled out with his mind still stretched into the past. It wasn’t until they were on the street that he was jerked back to the present by the fire engines clangling, flashing their murder-red lights, the siren sounds cutting the hot blue-serge air. Miss Horwitz talking to herself and him at once enjoying ahead of time the piles of ashes and bricks they were to see. Her body looked carved out of a mass of brown shoe polish and as matter-of-fact as a shoe lace, but her eyes were shining.

“Come on Coin, stop dawdling along, you’ll have plenty of time for that when your sister Agnes slaps you unconscious because you didn’t use the sense you were born with.”

They didn’t have the sense they were born with letting him out to lead around a drunken blind man who spent most of his time playing the numbers and feeling-up Mrs. Walker. He wondered why his Sister Agnes skipped around Miss Mayonnaise-smelling Horwitz, when she was so cross all the time and walked as if she always had the bathroom on her mind. She was looking at him now, reading his mind probaby. Flushing his thoughts.

“Coin, you look like you’ve been starved to death. On the way home we’ll stop by the Y.W.C.A. and get something good to eat. And I have some candy in my room. That might sweeten that sour face of yours”.

Just when he was beginning to hate her she got so nice an all day lollypop would dissolve in her mouth. I bet she doesn’t have peppermint as long as the clown’s rope. And he laughed to himself.

“Would you like that?”

“Yes, Miss Horwitz.”

“Now we’re getting somewhere,” and she squeezed the sweat of her palm into his, making a sucking sound. If she’d only let his hand go. He was always being caught, trapped.

“We’d better go to Fort Green Park and look from there.

I suppose Agnes went there with the others. No use in us getting burned is there ? And you’ll be able to see everything. I’m not walking you too fast am I? You’re a big boy now, almost a young man. We want to get there before it’s all over,you know, before they put it out.”

She was talking in short pants. She seemed to want to run. She even let go of his hand in her hurry. She was almost laughing like the old sisters laughed in church when God won sinners.

“Coin, you’re going to miss it,” and she snatched up his hand again.

She’s happy because there’s burning down, she offered me candy because there’s terrible. She’s even running like a little girl for a favorite doll. The thoughts rammed into his head from where he’d never know.

As they rapidly climbed the hill of the park to the lookout Coin saw gazing east the puffing smoke lined with murder-red and straight ahead on the lookout, everywhere crowds of people strained in one direction: toward the burning grave where they once had praised the Lord. He was sweaty hot but shivered cold as they passed group after group. Miss Horwitz smiled now and again to people she knew. No one smiled back or even noticed. Only the sound of fire laughing in nanny goat sounds, sneezing, harking, spitting, biting the air for food. On a high rock stood Reverend Brooks, hands behind his back like a prisoner waiting for the noose, (He had preached his mother’s funeral: “I am the resurrection and the life and the light…” …“She is not sealed in this coffin, she has already arisen and is in our midst like a star to guide us. Naomi Starr Foreman…”) or a statue prophet doomsday couldn’t melt. Next to him was his mother’s old nurse, Mrs. Quick, who had urged him to become a Christian so that he could pray for his mother to get well. (She had said to him before his mother went to the faith-healer to be cured of her paralysis: “Then the needy brings up their affliction and they kneels down and he prays for each and everyone separate and they think real deep on the Lord. Many rise up well and cured.”)

“Is Mama…?” he had asked in that long ago.

“Your mother’s got the strength and faith to remove mountains.” His mother was dead but Mrs. Quick was still on the Lord’s side. Coin moved away.