Issue 28, Summer-Fall 1962

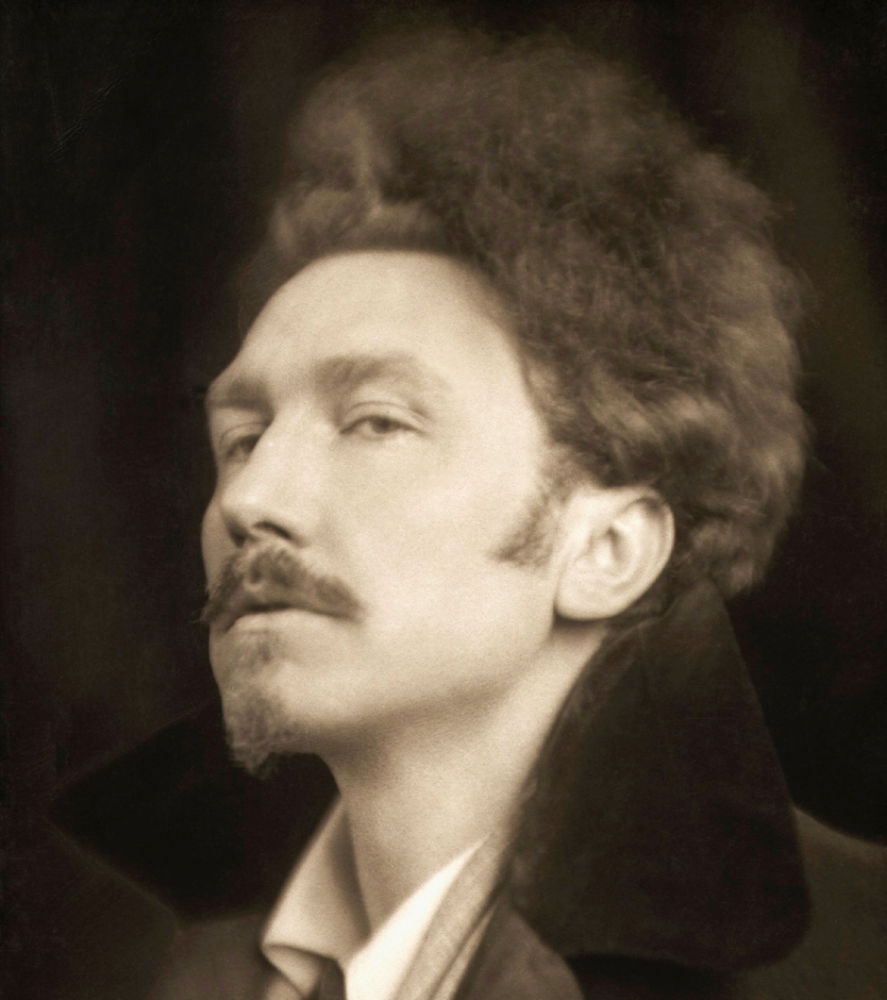

Ezra Pound, ca. 1913.

Ezra Pound, ca. 1913.

Since his return to Italy, Ezra Pound has spent most of his time in the Tirol, staying at Castle Brunnenburg with his wife, his daughter Mary, his son-in-law Prince Boris de Rachewiltz, and his grandchildren. However, the mountains in this resort country near Merano are cold in the winter, and Mr. Pound likes the sun. The interviewer was about to leave England for Merano, at the end of February, when a telegram stopped him at the door: “Merano icebound. Come to Rome.”

Pound was alone in Rome, occupying a room in the apartment of an old friend named Ugo Dadone. It was the beginning of March and exceptionally warm. The windows and shutters of Pound’s corner room swung open to the noises of the Via Angelo Poliziano. The interviewer sat in a large chair while Pound shifted restlessly from another chair to a sofa and back to the chair. Pound’s impression on the room consisted of two suitcases and three books: the Faber Cantos, a Confucius, and Robinson’s edition of Chaucer, which he was reading again.

In the social hours of the evening—dinner at Crispi’s, a tour among the scenes of his past, ice cream at a café—Pound walked with the swaggering vigor of a young man. With his great hat, his sturdy stick, his tossed yellow scarf, and his coat, which he trailed like a cape, he was the lion of the Latin Quarter again. Then his talent for mimicry came forward, and laughter shook his gray beard.

During the daytime hours of the interview, which took three days, he spoke carefully and the questions sometimes tired him out. In the morning when the interviewer returned, Mr. Pound was eager to revise the failures of the day before.

INTERVIEWER

You are nearly through the Cantos now, and this sets me to wondering about their beginning. In 1916 you wrote a letter in which you talked about trying to write a version of Andreas Divus in Seafarer rhythms. This sounds like a reference to Canto 1. Did you begin the Cantos in 1916?

EZRA POUND

I began the Cantos about 1904, I suppose. I had various schemes, starting in 1904 or 1905. The problem was to get a form—something elastic enough to take the necessary material. It had to be a form that wouldn’t exclude something merely because it didn’t fit. In the first sketches, a draft of the present first Canto was the third.

Obviously you haven’t got a nice little road map such as the Middle Ages possessed of Heaven. Only a musical form would take the material, and the Confucian universe as I see it is a universe of interacting strains and tensions.

INTERVIEWER

Had your interest in Confucius begun in 1904?

POUND

No, the first thing was this: you had six centuries that hadn’t been packaged. It was a question of dealing with material that wasn’t in the Divina Commedia. Hugo did a Légende des Siècles that wasn’t an evaluative affair but just bits of history strung together. The problem was to build up a circle of reference—taking the modern mind to be the medieval mind with wash after wash of classical culture poured over it since the Renaissance. That was the psyche, if you like. One had to deal with one’s own subject.

INTERVIEWER

It must be thirty or thirty-five years since you have written any poetry outside the Cantos, except for the Alfred Venison poems. Why is this?

POUND

I got to the point where, apart from an occasional lighter impulse, what I had to say fitted the general scheme. There has been a good deal of work thrown away because one is attracted to a historic character and then finds that he doesn’t function within my form, doesn’t embody a value needed. I have tried to make the Cantos historic (vid. G. Giovannini, re relation history to tragedy. Two articles ten years apart in some philological periodical, not source material but relevant) but not fiction. The material one wants to fit in doesn’t always work. If the stone isn’t hard enough to maintain the form, it has to go out.

INTERVIEWER

When you write a Canto now, how do you plan it? Do you follow a special course of reading for each one?

POUND

One isn’t necessarily reading. One is working on the life vouchsafed, I should think. I don’t know about method. The what is so much more important than how.

INTERVIEWER

Yet when you were a young man, your interest in poetry concentrated on form. Your professionalism, and your devotion to technique, became proverbial. In the last thirty years, you have traded your interest in form for an interest in content. Was the change on principle?

POUND

I think I’ve covered that. Technique is the test of sincerity. If a thing isn’t worth getting the technique to say, it is of inferior value. All that must be regarded as exercise. Richter in his Treatise on Harmony, you see, says, “These are the principles of harmony and counterpoint; they have nothing whatever to do with composition, which is quite a separate activity.” The statement, which somebody made, that you couldn’t write Provençal canzoni forms in English, is false. The question of whether it was advisable or not was another matter. When there wasn’t the criterion of natural language without inversion, those forms were natural, and they realized them with music. In English the music is of a limited nature. You’ve got Chaucer’s French perfection, you’ve got Shakespeare’s Italian perfection, you’ve got Campion and Lawes. I don’t think I got around to this kind of form until I got to the choruses in the Trachiniae. I don’t know that I got to anything at all, really, but I thought it was an extension of the gamut. It may be a delusion. One was always interested in the implication of change of pitch in the union of motz et son, of the word and melody.

INTERVIEWER

Does writing the Cantos, now, exhaust all of your technical interest, or does the writing of translations, like the Trachiniae you just mentioned, satisfy you by giving you more fingerwork?

POUND

One sees a job to be done and goes at it. The Trachiniae came from reading the Fenollosa Noh plays for the new edition, and from wanting to see what would happen to a Greek play, given that same medium and the hope of its being performed by the Minorou company. The sight of Cathay in Greek, looking like poetry, stimulated crosscurrents.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that free verse is particularly an American form? I imagine that William Carlos Williams probably does, and thinks of the iambic as English.

POUND

I like Eliot’s sentence: “No verse is libre for the man who wants to do a good job.” I think the best free verse comes from an attempt to get back to quantitative meter.

I suppose it may be un-English without being specifically American. I remember Cocteau playing drums in a jazz band as if it were a very difficult mathematical problem.

I’ll tell you a thing that I think is an American form, and that is the Jamesian parenthesis. You realize that the person you are talking to hasn’t got the different steps, and you go back over them. In fact the Jamesian parenthesis has immensely increased now. That I think is something that is definitely American. The struggle that one has when one meets another man who has had a lot of experience to find the point where the two experiences touch, so that he really knows what you are talking about.

INTERVIEWER

Your work includes a great range of experience, as well as of form. What do you think is the greatest quality a poet can have? Is it formal, or is it a quality of thinking?

POUND

I don’t know that you can put the needed qualities in hierarchic order, but he must have a continuous curiosity, which of course does not make him a writer, but if he hasn’t got that he will wither. And the question of doing anything about it depends on a persistent energy. A man like Agassiz is never bored, never tired. The transit from the reception of stimuli to the recording, to the correlation, that is what takes the whole energy of a lifetime.