Issue 28, Summer-Fall 1962

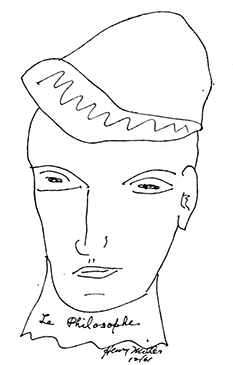

Henry Miller: Self portrait.

Henry Miller: Self portrait.

In 1934, Henry Miller, then aged forty-two and living in Paris, published his first book. In 1961 the book was finally published in his native land, where it promptly became a best-seller and a cause célèbre. By now the waters have been so muddied by controversy about censorship, pornography, and obscenity that one is likely to talk about anything but the book itself.

But this is nothing new. Like D. H. Lawrence, Henry Miller has long been a byword and a legend. Championed by critics and artists, venerated by pilgrims, emulated by beatniks, he is above everything else a culture hero—or villain, to those who see him as a menace to law and order. He might even be described as a folk hero: hobo, prophet, and exile, the Brooklyn boy who went to Paris when everyone else was going home, the starving bohemian enduring the plight of the creative artist in America, and in latter years the sage of Big Sur.

His life is all written out in a series of picaresque narratives in the first-person historical present: his early Brooklyn years in Black Spring, his struggles to find himself during the twenties in Tropic of Capricorn and the three volumes of the Rosy Crucifixion, his adventures in Paris during the thirties in Tropic of Cancer.

In 1939 he went to Greece to visit Lawrence Durrell; his sojourn there provides the narrative basis of The Colossus of Maroussi. Cut off by the war and forced to return to America, he made the yearlong odyssey recorded in The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. Then in 1944 he settled on a magnificent empty stretch of California coast, leading the life described in Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. Now that his name has made Big Sur a center for pilgrimage, he has been driven out and is once again on the move.

At seventy Henry Miller looks rather like a Buddhist monk who has swallowed a canary. He immediately impresses one as a warm and humorous human being. Despite his bald head with its halo of white hair, there is nothing old about him. His figure, surprisingly slight, is that of a young man; all his gestures and movements are young.

His voice is quite magically captivating, a mellow, resonant but quiet bass with great range and variety of modulation; he cannot be as unconscious as he seems of its musical spell. He speaks a modified Brooklynese frequently punctuated by such rhetorical pauses as “Don’t you see?” and “You know?” and trailing off with a series of diminishing reflective noises, “Yas, yas … hmm … hmm … yas … hm … hm.” To get the full flavor and honesty of the man, one must hear the recordings of that voice.

The interview was conducted in September 1961, in London.

INTERVIEWER

First of all, would you explain how you go about the actual business of writing? Do you sharpen pencils like Hemingway, or anything like that to get the motor started?

HENRY MILLER

No, not generally, no, nothing of that sort. I generally go to work right after breakfast. I sit right down to the machine. If I find I’m not able to write, I quit. But no, there are no preparatory stages as a rule.

INTERVIEWER

Are there certain times of day, certain days when you work better than others?

MILLER

I prefer the morning now, and just for two or three hours. In the beginning I used to work after midnight until dawn, but that was in the very beginning. Even after I got to Paris I found it was much better working in the morning. But then I used to work long hours. I’d work in the morning, take a nap after lunch, get up and write again, sometimes write until midnight. In the last ten or fifteen years, I’ve found that it isn’t necessary to work that much. It’s bad, in fact. You drain the reservoir.

INTERVIEWER

Would you say you write rapidly? Perlès said in My Friend Henry Miller that you were one of the fastest typists he knew.

MILLER

Yes, many people say that. I must make a great clatter when I write. I suppose I do write rapidly. But then that varies. I can write rapidly for a while, then there come stages where I’m stuck, and I might spend an hour on a page. But that’s rather rare, because when I find I’m being bogged down, I will skip a difficult part and go on, you see, and come back to it fresh another day.

INTERVIEWER

How long would you say it took you to write one of your earlier books once you got going?

MILLER

I couldn’t answer that. I could never predict how long a book would take: even now when I set out to do something I couldn’t say. And it’s somewhat false to take the dates the author says he began and ended a book. It doesn’t mean that he was writing the book constantly during that time. Take Sexus, or take the whole Rosy Crucifixion. I think I began that in 1940, and here I’m still on it. Well, it would be absurd to say that I’ve been working on it all this time. I haven’t even thought about it for years at a time. So how can you talk about it?

INTERVIEWER

Well, I know that you rewrote Tropic of Cancer several times, and that work probably gave you more trouble than any other, but of course it was the beginning. Then too, I’m wondering if writing doesn’t come easier for you now?

MILLER

I think these questions are meaningless. What does it matter how long it takes to write a book? If you were to ask that of Simenon, he’d tell you very definitely. I think it takes him from four to seven weeks. He knows that he can count on it. His books have a certain length usually. Then too, he’s one of those rare exceptions, a man who when he says, “Now I’m going to start and write this book,” gives himself to it completely. He barricades himself, he has nothing else to think about or do. Well, my life has never been that way. I’ve got everything else under the sun to do while writing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you edit or change much?

MILLER

That too varies a great deal. I never do any correcting or revising while in the process of writing. Let’s say I write a thing out any old way, and then, after it’s cooled off—I let it rest for a while, a month or two maybe—I see it with a fresh eye. Then I have a wonderful time of it. I just go to work on it with the ax. But not always. Sometimes it comes out almost like I wanted it.

INTERVIEWER

How do you go about revising?

MILLER

When I’m revising, I use a pen and ink to make changes, cross out, insert. The manuscript looks wonderful afterwards, like a Balzac. Then I retype, and in the process of retyping I make more changes. I prefer to retype everything myself, because even when I think I’ve made all the changes I want, the mere mechanical business of touching the keys sharpens my thoughts, and I find myself revising while doing the finished thing.

INTERVIEWER

You mean there is something going on between you and the machine?

MILLER

Yes, in a way the machine acts as a stimulus; it’s a cooperative thing.

INTERVIEWER

In The Books in My Life, you say that most writers and painters work in an uncomfortable position. Do you think this helps?

MILLER

I do. Somehow I’ve come to believe that the last thing a writer or any artist thinks about is to make himself comfortable while he’s working. Perhaps the discomfort is a bit of an aid or stimulus. Men who can afford to work under better conditions often choose to work under miserable conditions.

INTERVIEWER

Aren’t these discomforts sometimes psychological? You take the case of Dostoyevsky …

MILLER

Well, I don’t know. I know Dostoyevsky was always in a miserable state, but you can’t say he deliberately chose psychological discomforts. No, I doubt that strongly. I don’t think anyone chooses these things, unless unconsciously. I do think many writers have what you might call a demonic nature. They are always in trouble, you know, and not only while they’re writing or because they’re writing, but in every aspect of their lives, with marriage, love, business, money, everything. It’s all tied together, all part and parcel of the same thing. It’s an aspect of the creative personality. Not all creative personalities are this way, but some are.