Issue 222, Fall 2017

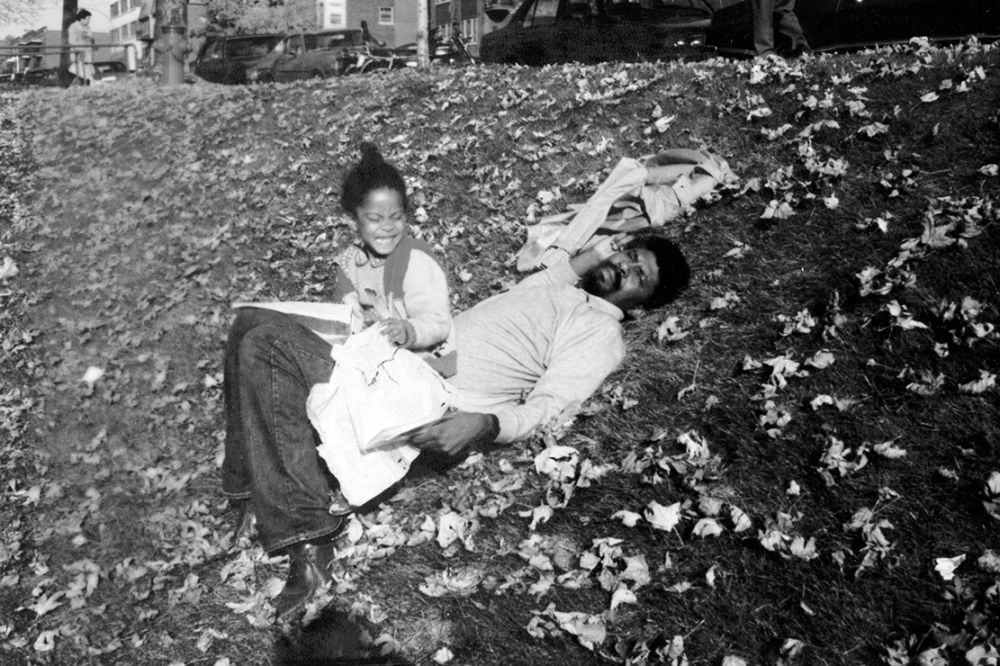

Laferrière with his eldest daughter, Melissa.

Dany Laferrière was born in Port-au-Prince in 1953. After his father, a former mayor of the city, was forced into exile in 1959, Dany was raised by his grandmother in the coastal village of Petit-Goâve. He returned to Port-au-Prince five years later and eventually became a culture reporter for Le petit samedi soir and Radio Haiti-Inter. When his colleague and friend Gasner Raymond was assassinated in 1976, Laferrière fled to Montreal, where he supported himself with a series of odd jobs. In 1985, he published his first novel, How to Make Love to a Negro Without Getting Tired, which chronicled those first years of his exile. But it wasn’t until 2009, when he received the Prix Médicis for his nineteenth book, The Return, that Laferrière reached a wide readership in France. Like his other books, The Return is drawn from his real-life experience, in this case the journey he made to bury his father’s ashes in Haiti.

Laferrière has written in prose and verse (The Return contains both); apart from his novels, he has published books for children and books that could be described as un-self-help, such as L’art presque perdu de ne rien faire (The Almost Forgotten Art of Doing Nothing, 2011) and Tout ce qu’on ne te dira pas, Mongo (Everything They Won’t Tell You, Mongo, 2015), a guide for newly arrived immigrants to the First World. All of his books are interconnected and autobiographical: his oeuvre, approaching thirty volumes, is one long book about his writing of that book. He lives in Montreal with Maggie Berrouët, his wife of thirty-eight years, and their three daughters.

Before this interview began, Laferrière warned me that he is notorious for speaking at length: “I’m not a reticent Evan S. Connell type—je me raconte.” Which proved true. He is open, warm, ironic, and quick to contradict himself as need be. Our interview took place over five sessions and several phone calls. The first meeting occurred on a lawn at Middlebury College in Vermont, where he was writer in residence; the second at a tavern near carré Saint-Louis, in Montreal, the setting of many of his books; the third in the back room of a Montreal bookstore; the fourth in his dining room and study. The final meeting took place at a restaurant in Paris, over a shared order of cervelle—that is, we shared a brain, an experience that will be familiar to many of his readers.

INTERVIEWER

In 2013, you were elected to the Académie française, the first-ever Haitian or Quebecois writer to join their ranks.

Laferrière

Yes, but first they had to sort out whether I was even admissible. You are supposed to be French. It turns out this wasn’t a written rule. At the time the rules were written, they couldn’t even imagine including someone not born in France or a French colony or département, or a naturalized Frenchman. A Haitian in Montreal is none of the above. To be eligible, you also have to live in France—which I did not. So the question became, is it the Académie française as in the French language? Or as in France? The president of the République decided the question—it’s the Académie of the French language. This decision permitted my candidacy to proceed. It was what they call “une belle élection.” I was received with enthusiasm, in the first round of voting. It took Victor Hugo something like four rounds, Voltaire three!

INTERVIEWER

What do you actually do there, beneath the dome?

Laferrière

I am part of several commissions, involving the dictionary, literature, and francophonie. I attend the weekly grandes séances on Thursdays. We discuss académie business, we grant literary awards and prizes, we revise definitions of words, all sorts of things.

INTERVIEWER

How do you discuss a word?

Laferrière

If a word that was used by Flaubert or Césaire falls into desuetude, if it becomes passé, we still keep it in the dictionary because it was used by an important writer. The dictionary strives to recognize the creative usage of writers. Our commission not long ago tackled the word sexe. So we looked at how writers use a word like sexe—all the different notions, phrases, and implications that have come up over the years. The Marquis de Sade doesn’t have the same thoughts on the matter as, say, the Marquise de Sévigné. An ordinary word can take up half a page in the dictionary. A word like sexe can run to six or seven pages.

INTERVIEWER

How did you contribute to defining that particular word?

Laferrière

The dictionary doesn’t have individual contributions. It’s like building a cathedral. The workers are unknown. But one of the things I tend to do is suggest that it might be interesting to have examples of things that aren’t from France. If it’s a wind, which we worked on recently, does it always have to be the mistral? What about the winds of elsewhere? How about zephyrs or siroccos? In French, there exists an enormous variety of classifications, proverbs, and witticisms about winds. There are winds that push ships as well as winds that come from the gut—the noisy, bodily winds of Rabelais. All shadings have to be in the dictionary. And in circumstances like this, you realize that people always remain, in a way, children—even august adults. Words that concern the inner workings of the human body can still provoke a smile or a laugh, even within the Académie française.

INTERVIEWER

You are known for your memorable titles, which are often playful. Did I Am a Japanese Writer really start with the title?

Laferrière

It certainly did. My publisher in Paris was interested in the ways that Caribbean and Creole writers treat the question of identity. I wasn’t at all interested in that. What interested me was, if literature belongs to everyone, if books belong to everyone, if anyone can go buy any book at a bookstore as soon as they get some money together—and if you can even buy a book without being able to read—then why can’t we be whatever kind of writers we want to be?