Issue 218, Fall 2016

“I am not much of a morning person,” Jeremy Prynne warned us, as we made arrangements for this interview. “My natural habitat seems to be the hours of darkness, ad libitum. So I’ll be pretty useless until about ten thirty or eleven a.m. at best: but at the other end of the day I never tire.”

So it proved. For four days at the end of January, we met after lunch in his rooms at Gonville and Caius College, at the University of Cambridge, and talked, with a break for dinner, until we pleaded exhaustion sometime after midnight. At the conclusion of each day’s interview, Prynne graciously walked us out through the sixteenth-century Gate of Honour before returning to his desk in the rooms he has kept since he was first appointed as a fellow, in 1962.

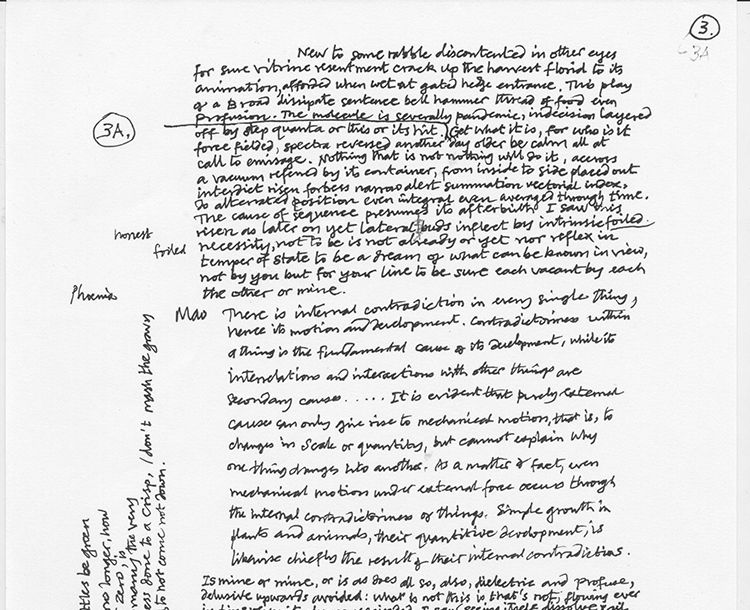

Prynne’s lower room is large and bright and stocked with English literature, its classical forbears, its Continental peers. (On the first day of our visit, he gave us keys and allowed us to browse in the mornings. Almost every book was annotated in his elegant script.) The upper room is smaller, cozier, and home to American and Chinese literature. Scrolls and framed sheets of calligraphy crowd the shelves. For decades these rooms have been the site of Prynne’s supervisions with Cambridge undergraduate and graduate students, on poetry from William Langland to Paul Celan and Frank O’Hara. (His tastes are unexpected and definite.) The rooms have also, over the decades, been a late-night meeting place for local and visiting poets.

Prynne is eighty, and he stands over six feet tall. Each afternoon of our visit, he folded himself into a low easy chair in his upper room and talked candidly and unflaggingly, with genial precision. When amused, he clapped his hands three times in brisk delight; when it occurred to him to show us a book, as it often did, he was up out of his chair to find it before we could stir to help. On the third day of the interview, he gave us a tour of the Gonville and Caius Library, where he served as Librarian of the College from 1969 to 2006.

Prynne published his first book of poems, Force of Circumstance, in 1962, and disowned it not long after. His next three books appeared in 1968, and since then he has steadily published a book every year or two. The collections have all appeared in small editions from presses based mainly in Cambridge. As his reputation has grown, the books have maintained a samizdat quality. With the exception of The White Stones (1969), which New York Review Books republished this year, they are hard to find. (A bibliography is available at prynnebibliography.org.) In 1982, he collected the books in Poems, which has been updated in three subsequent editions. He has also published commentaries, lectures, reviews, and letters on an astonishing array of topics.

Prynne’s poetry is powerful and dense. Each book is an experiment, made in a concentrated burst of effort: a mode of writing instigated by the academic calendar, with its rhythm of term and break. The poems investigate the languages of economics and the conditions of inequality; Marx and Mao are important influences. The poems also combine a deep knowledge of science with practical expertise in geology and botany: the devotions of a naturalist are frequently audible. And always there is literature: the history of English poetry, and the collective, global memory of the English language.

During the interview, Prynne often referred to his etymological dictionary (Barnhart’s), doubled in bulk by his interleaved notes, citations, and correspondence with the editors of the OED. The difficulty of his language, the liberties of his syntax, and the complexity of his prosody have steadily increased as he approached the volume most discussed here, Kazoo Dreamboats; or, On What There Is (2011). He freely conceded that the poems are not written with the reader in mind. How this can seem a necessary and even generous commitment, of a piece with his career as a dedicated teacher, is one of the mysteries of his poetry.

This is the first substantial interview Prynne has given. The final transcript came to 152,000 words—495 printed pages. At Prynne’s insistence, we have rendered his words in their English spellings. He declined to provide photographs. The edited fragment we print here begins during a discussion about a poetry reading that we had just attended together.

—Jeff Dolven and Joshua Kotin

PRYNNE

These poems we heard this evening, some of them were quite witty, some of them were adept. But they’re all poems written by a poet, and I could do without that. I want a poet to break out of his or her poetic identity, to establish a whole new set of possibilities for the reader and for him- or herself. To hear poems that must have been written by a poet is to find them trapped in the poetic habits from which they originate. There wasn’t a poem anywhere in that sequence that I heard that I would have been glad to read for a second time. They’re all perfectly okay—humorous, relaxed, and entertaining, and extend his working practice. But they wouldn’t do anything for me. You know? I can’t imagine why he did them. What was the motive? What was the serious development of his practice that poems like that would help him to find his way to? It didn’t seem to be that those questions had any good answers.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s talk about the development of your practice. You were an undergraduate here at Cambridge. Tell us about your work with the scholar and poet Donald Davie.

PRYNNE

My teacher when I was a student in my third year was Donald Davie, who was a poet, and we came to know each other quite well. I couldn’t say that I knew him warmly, but I did have a good regard for him because he was a serious scholar. He’d written Articulate Energy (1955). He’d written a number of books of poems, all of which I’d studied quite closely. We did work on Pound, we did work on Eliot, we did work on Stevens, we did work on Yeats, and had spirited discussions of each. So the English scene with regard to late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century poetry was part of our remit. We were active with it. And my interest in American poets flowed out of that.

Davie wanted very much to be a poet. I think he probably knew in his heart of hearts that he actually wasn’t a poet, though he cared enough about poetry to commit himself to substantial efforts to develop some way of expanding his own writing practice. He was part of that Movement group of poets who wrote very defensively and traditionally, and Davie’s way out of that was to be interested in Eliot. His further way out of it was to be interested in Pound—and to be interested in Pound was not at that time conventional. Robert Conquest and the English Movement poets didn’t care much about Pound. He was just too wild. They took example from Eliot because Eliot was a more defensive and traditional mind. His adroitly ironical, evasive temper suited them and their world pretty well, and insofar as that world had important experimental and innovative features, they were largely derived from Empson. Empson had little connection with Eliot and not much interest in Pound, so far as I know. But he was a very individual and eccentric and important figure amongst the writers in that era. Quite important to Davie.

INTERVIEWER

Did Davie introduce you to any younger poets?

PRYNNE

Davie introduced me to the name of Charles Tomlinson. He’d been Tomlinson’s teacher when Tomlinson was a student here. An important starting point for Tomlinson as a poet was Wallace Stevens. I had read a little of Stevens as a student before I came into connection with Davie, but there’s no doubt that my connection with Davie and through him with Tomlinson opened the door to Stevens as an important writer. That was a significant moment, too, because a world that had previously been occupied more or less exclusively by Pound and Williams now opened to another presence of a very different kind, a seriously intellectual poet of cerebral focus, committed to an active intelligence of mind. This was quite distinct from anything that I’d found in Pound, or in Creeley, or in Olson, come to that.

Tomlinson was a seriously intelligent poet but he was also a descriptive poet who wrote about the natural scene in a way that Stevens wouldn’t do. Of course, that aroused a certain Englishness in me because I knew those landscapes and was party to them and produced by them. Not from Tomlinson’s part of the world, but nonetheless, it was a very English kind of activity. So reading that and reading Stevens and starting to think about composing poems offered a great number of competing possibilities all converging upon each other.

My early writing habits were not very distinctive. I would write these poems. I can’t say they gave me much satisfaction. I wrote them as best I knew how. When I’d done them, I thought, Well, they’re all I can do, up to this moment.

INTERVIEWER

These are the poems in Force of Circumstance, your first book?

PRYNNE

Now I’m in danger of confabulating. By the time Force of Circumstance was being prepared for publication, I’d fallen out of love with it. I would probably have suppressed it if it had been a practical possibility at the time. It had some of Davie’s fingerprints on it, it had some of Tomlinson’s fingerprints. It had a few other facile fingerprints of my own on it. If this was being a poet, it was not a very inviting idea. Here I’m probably inventing, but I did have the sense then that if I didn’t start, wherever best I could, I would never go on. I had to start somewhere. It was going to be uncomfortable, disorderly, imitative, facile, foolish, childish—but I had to put this stuff down and do all these things because otherwise I’d never get past the starting block. I just had to go through the formalities of putting it into the outside world for readers to look at, and turn up their lips at, as I would, too, if I were one of its readers. Think of the very young Keats! Because I’d got to get past this point, and there was no other way to get past it. I had to work my way through, almost like the psychoanalytic process, and have the extremely uncomfortable experience of being an incompetent beginner.

With my best and not even particularly advanced critical reading self, I could see perfectly well that this work was not distinctive. It was imitative, and it didn’t have much in the way of strong possibilities. I was seeing all this strong possibility in the Don Allen anthology, but I knew I wasn’t going to be able to tune into that in a very convincing way because the English nature of the English language and its English resources inhibited that transfer. It was not a transfer that could be made just like that. So being a poet at that stage was very discomfiting.

INTERVIEWER

What were your initial impressions of Allen’s 1960 anthology, The New American Poetry?

PRYNNE

My copy was paperback and it fell to pieces out of intensive use. It became a loose-leaf assemblage because the back strip collapsed. It was not by any means just the star items that I read, I read Robert Duncan, I read of course all the Creeley items and the Olson items. But there was a lot of other material there. Kerouac, for example, wrote about automatic writing, and it was all completely new territory—I’d never seen anything like it before. What’s more, it was full of energy and wackiness and innovation, and none of the English writers I had any knowledge of would ever have committed themselves to behaviour like that. It was not what authors were supposed to do. Being an author, certainly being a poet, was defensive and traditional and habit-forming, and Eliot and Yeats were the chief formative presences. Auden was around the place and was a slightly dangerous author. The Donald Allen anthology seemed to be a completely different world.

It wasn’t exactly that the ideas or the arguments registered strongly with me. It was that the energy and innovativeness and newness of outlook, and the experiments with forms, prosodies, rhythms, and matters of presentation, including the whole mise-en-page, were completely unprecedented in English practice at the time. To break up the presence of the word forms across the page and to distribute them according to rhythm and emphasis was unprecedented in British habit.