Issue 209, Summer 2014

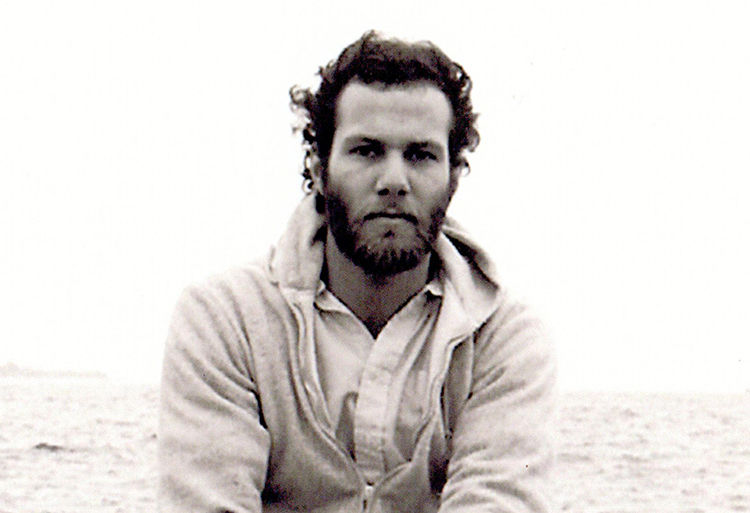

In Nags Head, North Carolina, 1978.

In Nags Head, North Carolina, 1978.

Henri Cole lives alone in a small, bright apartment on the top floor of a five-story building in the South End neighborhood of Boston. He works in solitude many hours a day. Cole comes from a family of five children, raised in Virginia. His older brother was a colonel in the Marine Corps; at six feet tall, with his erect bearing, long arms, and capable hands, Cole could be mistaken for a former marine himself. He shows the unfailing politeness of many Southern men; his voice and manner have a marked gentleness about them. Yet underneath, you sense an iron will. It’s difficult to imagine him marching in step to anything but the rhythms in his own head.

He works at a large desk surrounded by prints and drawings by artists such as Louise Bourgeois, Vija Celmins, Jenny Holzer, and Kiki Smith (he has collaborated on projects with the last two). He prefers art made by women. Above an emerald-green couch hangs an etching by Smith, of a fawn, its legs folded under its long body, its big eyes looking guilelessly out of the picture. Each hair of its pelt is articulated, so that the creature seems uncannily present, although the model turns out to be not a living fawn but a piece of taxidermy. There is an analogy here with Cole’s poems: his language, as precise and distinct and elegantly astringent as those etched lines, has an uncanny quality, too. How he brings so much hidden feeling to the surface is a mystery that haunted this interview.

Cole has published eight books of poetry, including Pierce the Skin: Selected Poems, 1982–2007; a new collection, Nothing to Declare, will be published next spring. He is the recipient of many awards, including the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award, the Rome Prize, and the Jackson Poetry Prize. He teaches at Ohio State University and is the poetry editor of The New Republic.

Our conversations took place over three sessions last winter—two in Boston, one at an apartment in New York where Cole was a guest. On all three occasions, Cole offered me tea when I arrived and would ask with real interest about my own work and life; it took some effort to turn the conversation toward him.

—Sasha Weiss

INTERVIEWER

You’ve said you see yourself not as a confessional poet, but as an autobiographical poet. What’s the distinction? Your poems often use facts from your life.

COLE

A confessional poem is more diary-like and confined to the here and now and without much aesthetic dignity. When I am writing, there is no pleasure in revealing the facts of my life. Pleasure comes from the art-making impulse, from assembling language into art.

INTERVIEWER

And yet revelation is a fact of these poems. They feel intensely personal.

COLE

This is the result of artifice and extreme control. When I was forty, I lived in Rome and spent a year looking at Italian art—thousands of depictions of a man nailed to a cross and of the saints and martyrs—in which pain and suffering are in the foreground. I asked myself then what kind of poem I wanted to write. You could say that my time in Italy “Romanized” me and laid something bare. The experience made me ask why my poems were so academically descriptive and what I could do to change this. This was the beginning of a shift in style. Many of the poems in The Visible Man were written there. It’s my most astringent book, and though now, when I read it, I’m embarrassed by the contents—lines like “Why do I appear to be what I am not?/To the world, arrogantly self-sufficient./To myself, womanish, conflicted, subservient”—the book is a record of the person I was, and I feel pride in the young person who was able to write it all down. Some people speak of poetry as therapy, but I don’t have this experience. For me, the therapy is in finding the right words and getting them in the right order. There is not any therapy in personal revelation.

INTERVIEWER

It seems to me that your poems refuse therapy. They give us access to certain kinds of pain and grief, and then they leave us there.

COLE

I think it would be rather narrow—and moralistic—to say that poetry must comfort us and point to what is good. I don’t think that is the function of art, though sometimes it is a happy result. In any case, a sentimental, moralizing poem is not what I want to write. I don’t want the reader to experience comfort—I want the opposite. A lyric poem presents an X-ray of the self in a moment of being, and usually this means dissonance. I think immediately of the “sonnets of desolation” or “terrible sonnets” by Gerard Manley Hopkins, where there is no compulsion to hide the darkest corners of the soul.

INTERVIEWER

But do you feel any ethical responsibility as a poet?

COLE

No, though I admire poets who do, like Seamus Heaney. Using the Gospel story in which Christ draws a line in the sand with his finger to prevent a crowd from stoning an adulterous woman, Heaney says that writing can change things. Over time, occasionally, I have felt a need to speak as a gay man, since until recently we were not encouraged by society to love one another, marry, and have children. So if I have an ethics, it is simply to be true, but never at the expense of original language.

INTERVIEWER

In your first books, you are not out as a gay poet.

COLE

In the beginning, I used nature as a mask for writing about private feelings. Oscar Wilde says somewhere that man is least himself when writing in his own person. But give him a mask and he will tell you the truth. This, in part, is why myths and fairy tales are so valuable to poets—they are masks. And that’s what I was throwing off in The Visible Man—in addition to description and rhyme, which I felt had “nursed and embalmed me at once.” Instead, I want “to see the beast shitting in its cage,” as I say in “Arte Povera,” the opening poem of The Visible Man.

INTERVIEWER

When you wrote the poems in your next book, Middle Earth, in your mid-forties, it was as if your style had cooled.

COLE

I was born on the southernmost island of Japan, Kyushu, and lived there for only the first year of my life. When I finally returned, at forty-five, I lived in the foothills north of Kyoto, in two tatami-mat rooms, with a futon, a wok, a laptop, and very little else. It was the farthest I’d ever been from the West, but it was strangely familiar to me. It felt like I was the only white person there in the foothills, and I lived completely alone. It was a marvelous setting, where mountain life touched city life, so there were giant insects, like praying mantises—“I found a praying mantis on my pillow./‘What are you praying for?’ I asked. ‘Can you pray/for my father’s soul, grasping after Mother?’” Everything seemed kind of exaggerated and intensified by my loneliness. As in Rome, I asked myself again what kind of poem I would write. I could have written tankas and haikus, like an American travel poet, but I didn’t want to do this. So I spent many weeks just reading. Then I decided to try writing free-verse sonnets and bringing to them some of the qualities of Japanese poetry, valuing sincerity over artifice, frequent use of simile, the presence of nature as an emblem for interior states, and so on. The first poems I wrote were in a rather minimalist style, like a rock garden. I tried to write poems of pure contentment, because I was so deeply moved by the setting—the rice fields were being planted and were full of happy frogs that talked all night and accompanied my sleep. It was intense. And slowly, I wrote about it. And these were the poems that became Middle Earth.

INTERVIEWER

Did you speak any Japanese?

COLE

I took a Japanese-language course, but that was a failure. Then I studied tea ceremony and found a metaphor for what I was trying to do in the new poems. Everything is carefully choreographed in a tea ceremony, in part to arouse the senses. As a result, you hear the water bubbling in the pot, taste the delicious sweet cakes, consider the cluster of trees out the window, and read the scroll painting in the tokonoma. There was an elegant simplicity, or rough grace, which I wanted to translate into poetry.