Issue 44, Fall 1968

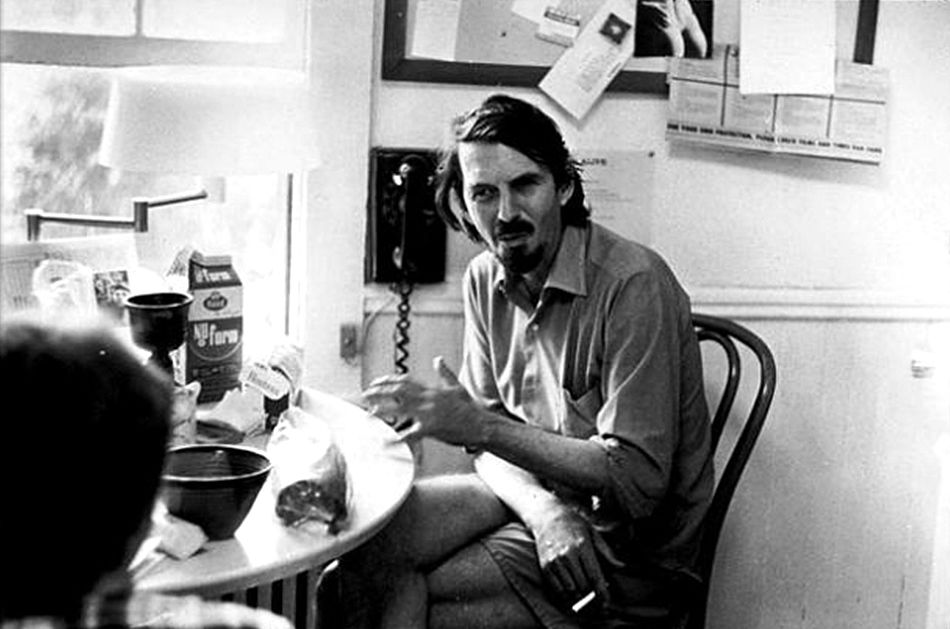

Robert Creeley, ca. 1972. Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

Robert Creeley, ca. 1972. Photograph by Elsa Dorfman

This is a composite interview. It combines two separate discussions with Robert Creeley—held at different times, and conducted by two different interviewers: Linda Wagner and Lewis MacAdams, Jr. The questions specifically devoted to the poet’s craft were put to Robert Creeley by Linda Wagner. She refers to the exchange as a “colloquy”—a term that Creeley insisted on because (as he put it) her questions were “active in their own assumptions … We are talking together.” She began the exchange at the 1963 Vancouver poetry sessions, continued it at Creeley’s 1964 Bowling Green, Ohio, reading, and finished it in August 1965, at the poet’s home in New Mexico.

MacAdams interviewed Creeley in the spring of 1968 in Eden, New York, a few miles from Buffalo where Creeley once spent the winter months teaching. “The first session was a failure,” MacAdams said of the interview. “Both of us were tired, and although Creeley was polite and voluble, I asked a bunch of dumb questions. The interview ended in the dark, everybody drunk and slightly morose. Then we adjourned to his driveway to shovel snow. We tried again two weeks later. The snow had stopped, the sun was out, and the Creeley house was full of his friends, among them the poets Allen Ginsberg, Robert Duncan, and Robin Blaser. After breakfast the two of us went upstairs to his study, a big sunny room looking out across a long wooded valley to Lake Erie. The study had once been a nursery; the framed photographs of Charles Olson and John Wieners and of Creeley’s wife, Bobbie, are set off by pink wallpaper, covered with horses and maids.”

INTERVIEWER

What do you think was the first impulse that set you on the course to being a writer?

ROBERT CREELEY

As a kid I used to be fascinated by people who, like they say, “traveled light.” My father died when I was very young, but there were things of his left in the house that my mother kept as evidences of his life: his bag, for example, his surgical instruments, even his prescription pads. These things were not only relics of his person, but what was interesting to me was that this instrumentation was peculiarly contained in this thing that he could carry in his hand. The doctor’s “bag.” One thinks of the idiom that is so current now, “bag,” to be in this or that “bag.” The doctor’s bag was an absolutely explicit instance of something you carry with you and work out of. As a kid, growing up without a father, I was always interested in men who came to the house with specific instrumentation of that sort—carpenters, repairmen—and I was fascinated by the idea that you could travel in the world that way with all that you needed in your hands … a Johnny Appleseed. All of this comes back to me when I find myself talking to people about writing. The scene is always this: “What a great thing! To be a writer! Words are something you can carry in your head. You can really ’travel light.’”

INTERVIEWER

You speak a great deal about the poet’s locale, his place, in your work. Is this a geographic term, or are you thinking of an inner sense of being?

CREELEY

I’m really speaking of my own sense of place. Where “the heart finds rest,” as Robert Duncan would say. I mean that place where one is open, where a sense of defensiveness or insecurity and all the other complexes of response to place can be finally dropped. Where one feels an intimate association with the ground underfoot. Now that’s obviously an idealization—or at least to hope for such a place may well be an idealization—but there are some places where one feels the possibility more intensely than others. I, for example, feel much more comfortable in a small town. I’ve always felt so, I think, because I grew up in one in New England. I like that spill of life all around, like the spring you get in New England with that crazy water, the trickles of water everyplace, the moisture, the shyness, and the particularity of things like blue jays. I like the rhythms of seasons, and I like the rhythms of a kind of relation to ground that’s evident in, say, farmers; and I like time’s accumulations of persons. I loved aspects of Spain in that way, and I frankly have the same sense of where I now am living in New Mexico. I can look out the window up into hills seven miles from where the Sandia Cave is located, perhaps the oldest evidence of man’s occupation of this hemisphere. I think it dates back to either 15,000 or 20,000 BC. and it’s still there. And again I’m offered a scale, with mountains to the southeast, the Rio Grande coming through below us to the west, and then that wild range of mesa off to the west. This is a very basic place to live. The dimensions are of such size and of such curious eternity that they embarrass any assumption that man is the totality of all that is significant in life. The area offers a measure of persons that I find very relieving and much more securing to my nature than would be, let’s say, the accumulations of men’s intentions and exertions in New York City. So locale is both a geographic term and the inner sense of being.

INTERVIEWER

Do you credit any one writer—ancestor or contemporary—with a strong influence on your poetry?

CREELEY

I think Williams gave me the largest example. But equally I can’t at all ignore Charles Olson’s very insistent influence upon me both in early times and now. And Louis Zukofsky’s. The first person who introduced me to writing as a craft, who even spoke of it as a craft, was Ezra Pound. I think it was my twentieth birthday that my brother-in-law took me down to a local bookstore in Cambridge and said, “What would you like? Would you like to get some books?” I bought Make It New and that book was a revelation to me. Pound spoke of writing from the point of view of what writing itself was, not what it was “about.” Not what symbolism or structure had led to, but how a man might address himself to the act of writing. And that was the most moving and deepest understanding I think I have ever gained. So that Pound was very important to my craft, no matter how much I may have subsequently embarrassed him by my own work. So many, many people—Robert Duncan, Allen Ginsberg, Denise Levertov, Paul Blackburn, Ed Dorn. I could equally say Charlie Parker—in his uses of silence, in his rhythmic structure. His music was influential at one point. So that I can’t make a hierarchy of persons.

INTERVIEWER

How about communicating with other writers when you were beginning?

CREELEY

I started writing to Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams about a magazine I was involved in. That’s how I got up courage to write them. I would have been too shy just to write them and say, “I think you are a great man.” To have business with them gave me reason. Pound wrote specifically, but he tended to write injunctions—“You do this. You do that. Read this. Read that.”

INTERVIEWER

Did you do everything he said?

CREELEY

I tried to. I couldn’t do it all. He would send books at times which would be useful. The History of Money by Alexander del Mar, which I read, and thought about. He was very helpful. It was very flattering to be taken at all seriously by him. Williams was always much more specific. At times he would do things which would … not dismay me, but my own ego would be set back. I remember one time I wrote him a very stern letter—some description about something I was going to do, or this was the way things were, blah blah. And he returned me the sheets of the letter and he had marked on the margin of particular sections, “Fine. Your style is tightening.” But I had the sense to know such comments were of more use to me than whether or not he approved of what I had to say. He would do things like that which were very good. While Pound would say, “Would you please tell me how old you are? You refer to having been involved in something for forty years. Are you twenty-three, or sixty-three?”

INTERVIEWER

At this point, were you raising pigeons in the country?

CREELEY

As a kid I’d had poultry, pigeons and chickens and what not. I’d married in 1946 and after a year on Cape Cod, we moved to a farm in New Hampshire where I attempted so-called sustenance farming. We had no ambitions that this would make us any income. We had a small garden that gave us produce for canning. It made the form of a day very active and interesting, something continuing—feed them, pluck them, take care of them in various ways. And I met a lovely man, a crazy, decisive breeder of Barred Rocks. He was quite small, almost elfin in various ways, with this crazy, intense, and beautifully articulate imagination. He could dowse for example, and all manner of crazy, mystical businesses that he took as comfortably as you’d take an ax in hand. No dismay, or confusion at all. A neighbor in New Hampshire would lose money in the woods. So he’d just cut a birch wand, and find it. The same way you’d turn on the lights to see what you’re doing. I remember one of these neighbors of ours, Howard Ainsworth, a woodcutter, was cutting pulp in the woods on a snowy day. But he had a hole in his pocket, and by the time he had discovered it, he’d lost a pocketful of change. So Howard simply cut himself a birch stick and he found it. It was nearly total darkness in the woods. He only remarked upon it, that is, how he’d found it, as an explanation of how he’d found it. I mean, it never occurred to him that it was more extraordinary than that.

INTERVIEWER

How did it occur to you?

CREELEY

I was fascinated by it—because it was a kind of “mysticism” which was so extraordinarily practical and unremoved. He had this crazy, yet practical way of exemplifying what he knew as experience. He used to paint, for example. Once he showed me this picture of a dog. He said, “What do you think of this? It’s one of my favorite dogs.” It was this white-and-black dog standing there looking incredibly sick. And I said, “Well, it’s a nice picture. But.” And he said, “Yes, it died three days later. That’s why it looks so sick.” He delighted me, you know, and I felt much more at home with him than with the more—not sophisticated—because I don’t think any man was more sophisticated in particular senses than he, but, god, he talked about things you could actually put your hand on. He would characterize patience, or how to pay attention to something.