Issue 72, Winter 1977

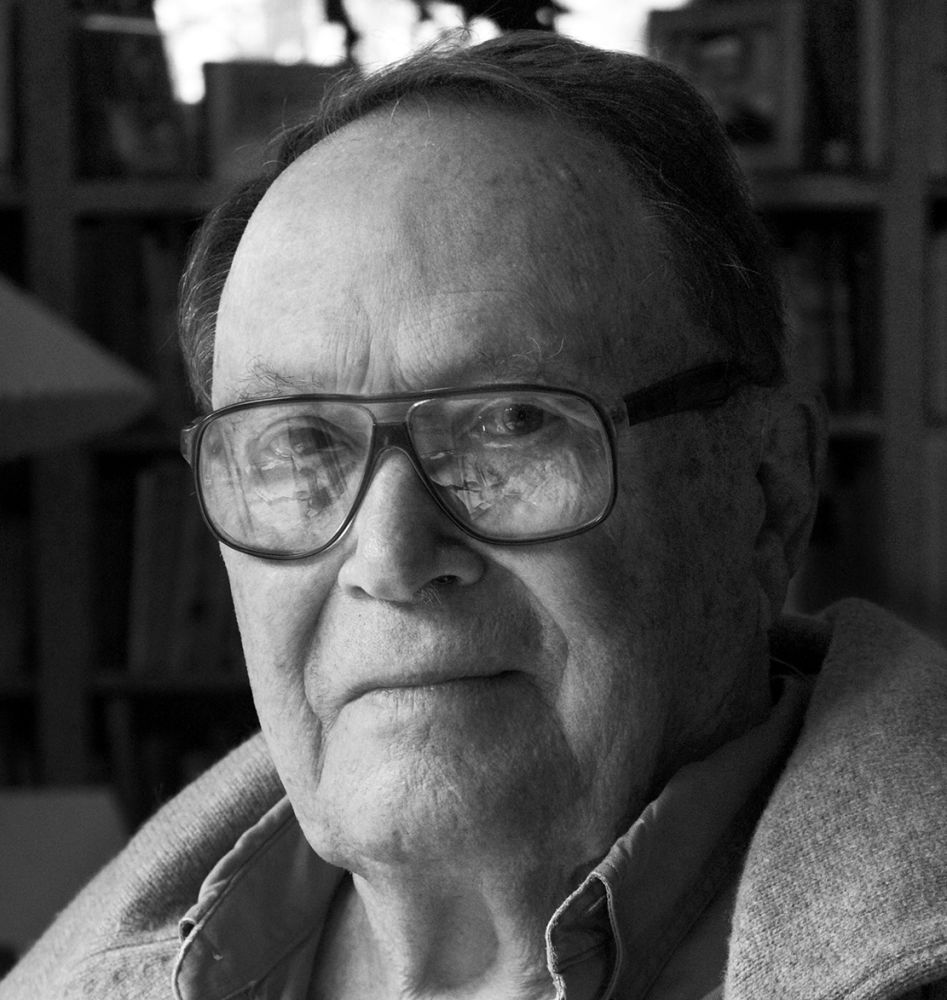

Photograph by VINCENT TOLENTINO

Photograph by VINCENT TOLENTINO

Note: Two interviews were done with Richard Wilbur. Because of the different nature of the questioning, the interviews have been kept separate. The first is by Peter Stitt, the second by Ellessa Clay High and Helen McCloy Ellison.

This interview took place at Richard Wilbur's home in the Berkshire Mountains near Cummington, Massachusetts, on a Saturday afternoon in March of 1977. Mr. Wilbur's house sits on a hillside surrounded by New England hill-country farms; there are no wheat fields, but plenty of trees and dairy cows. The room we talked in had a large window through which we could see the remnants of a winter of heavy snow.

Wilbur is a tall man who doesn't look his age—he leads an active life and takes good care of himself. He teaches during the fall semester and usually goes south for the winter. Recently he left Wesleyan University and became a writer in residence at Smith College, which is much closer to his home.

The Beautiful Changes and Other Poems, Wilbur's first book, appeared in 1947. His most recent books were both published in 1976—The Mind Reader: New Poems and Responses: Prose Pieces, 1953-1976. Mr. Wilbur has edited works by Poe, Shakespeare, and others, and his many translations include four plays by Molière, The Misanthrope, Tartuffe, The School for Wives, and The Learned Ladies. He is the recipient of several prizes and awards, including the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize, both of which were given for his Things of this World in 1957.

INTERVIEWER

When did you begin writing poetry?

WILBUR

I began writing poetry as a small child, and became a hired poet at the age of eight when my first poem was published in John Martin's Magazine. As I remember it, it was a horrible little poem about nightingales, which I never could have seen or heard as an American child. Of course, I wasn't thinking of poetry as my chief activity or even chief avocation at that age. I was drawing pictures, playing the piano vilely, thinking of being a cartoonist or a painter, and imagining that I might be a journalist. Poetry was just one of the many products, and I can't be said to have done anything very prodigious.

INTERVIEWER

Were you paid for the poem?

WILBUR

Yes, a dollar. I still have the dollar somewhere. Over there in that silo, which I cannot unlock because I've mislaid the key, there are all sorts of brown boxes full of memorabilia, and I think one of them contains the dollar.

INTERVIEWER

What eventually made you decide on a career as a poet?

WILBUR

I really drifted into it. When I was at Amherst College, I was Editor, or Chairman as they called it, of the College newspaper, and I did a lot of writing and drawing for the College humor magazine, Touchstone. At the same time, I felt a sort of vocation for the study of English literature and thought I might want to be a scholar. During World War II, I wrote poems to calm my own nerves and to send to my wife and a few friends, a few teachers at Amherst. Then when I came back after the war and went to Harvard on the G.I. Bill to get an M.A. in English, there was a friend we made there, a well-known French poet now, named André du Bouchet. He was involved with a little magazine called Foreground, which was being backed by Reynal and Hitchcock as a means of discovering new talent. André heard from my wife one evening that I had a secret cache of poems in my study desk. He asked to see them, then took them away to read. When he came back about an hour later, he kissed me on both cheeks and declared me to be a poet. He sent these poems off to Reynal and Hitchcock, and they also declared me to be a poet, saying that they would like to publish them, and others if I had them, as a book.

INTERVIEWER

How do you compose your poems? Do you write in long hand or on the typewriter? Do you write in bursts or long stretches, quickly or laboriously?

WILBUR

With pencil and paper and laboriously, very slowly on the whole. I do envy people who can compose on the typewriter, though I reject as preposterous Charles Olson's ideas about the relation of the typewriter to poetic form. I don't approach the typewriter until the thing is completely done, and whatever margins the typewriter might offer have nothing to do with the form of a poem as I conceive it. I write poems line by line, very slowly; I sometimes scribble alternative words in the margins rather densely, but I don't go forward with anything unless I am fairly satisfied that what I have set down sounds printable, sayable. I proceed as Dylan Thomas once told me he proceeded—it is a matter of going to one's study, or to the chair in the sun, and starting a new sheet of paper. On it you put what you've already got of a poem you are trying to write. Then you sit and stare at it, hoping that the impetus of writing out the lines that you already have will get you a few lines farther before the day is done. I often don't write more than a couple of lines in a day of, let's say, six hours of staring at the sheet of paper. Composition for me is, externally at least, scarcely distinguishable from catatonia.

INTERVIEWER

What is it that gets you started on a poem? Is it an idea, an image, a rhythm, or something else?

WILBUR

It seems to me that there has to be a sudden, confident sense that there is an exploitable and interesting relationship between something perceived out there and something in the way of incipient meaning within you. And what you see out there has to be seen freshly, or the process is not going to be provoked. Noting a likeness or resemblance between two things in nature can provide this freshness, but I think there must be more. For example, to perceive that the behavior of certain tree leaves is like the behavior of birds' wings is not, so far as I am concerned, enough to justify the sharpening of the pencil. There has to be a feeling that some kind of idea is implicit within that resemblance. It is strange how confident one can be about this. I always detest it when artists and writers marvel at their own creativity, but I think this is a very strange thing that most practiced artists would have in common, the certainty that accompanies these initial, provocative impressions. I am almost always right in feeling that there is a poem in something if it hits me hard enough. You can spoil your material, of course, but that doesn't mean the original feeling was false.

INTERVIEWER

You have been a teacher for many years. Does teaching complement your work as a poet?

WILBUR

I think the best part of teaching from the point of view of the teacher-writer, writer-teacher, is that it makes you read a good deal and makes you be articulate about what you read. You can't read passively because you have to be prepared to move other people to recognitions and acts of analysis. I know a few writers who don't teach and who, in consequence, do very little reading. This doesn't mean that they are bad writers, but in some cases I think they might be better writers if they read more. As for the experience of the classroom, I enjoy it; I am very depressed by classes that don't work, and rather elated by classes that do. I like to see if I can express myself clearly enough to stick an idea in somebody's head. Of course there are also disadvantages, one of which is that the time one spends teaching could be spent writing. Another involves this very articulateness of which I've been speaking. It uses the same gray cells, pretty much, that writing does, and so one can come to the job of writing with too little of a sense of rediscovery of the language. That is one reason I like to live out here in the country and lead a fairly physical life—play a lot of tennis, raise a lot of vegetables, go on a lot of long walks. I do things that are non-verbal so that I can return to language with excitement and move toward language from kinds of strong awareness for which I haven't instantly found facile words. It is good for a writer to move into words out of the silence, as much as he can.