Issue 107, Summer 1988

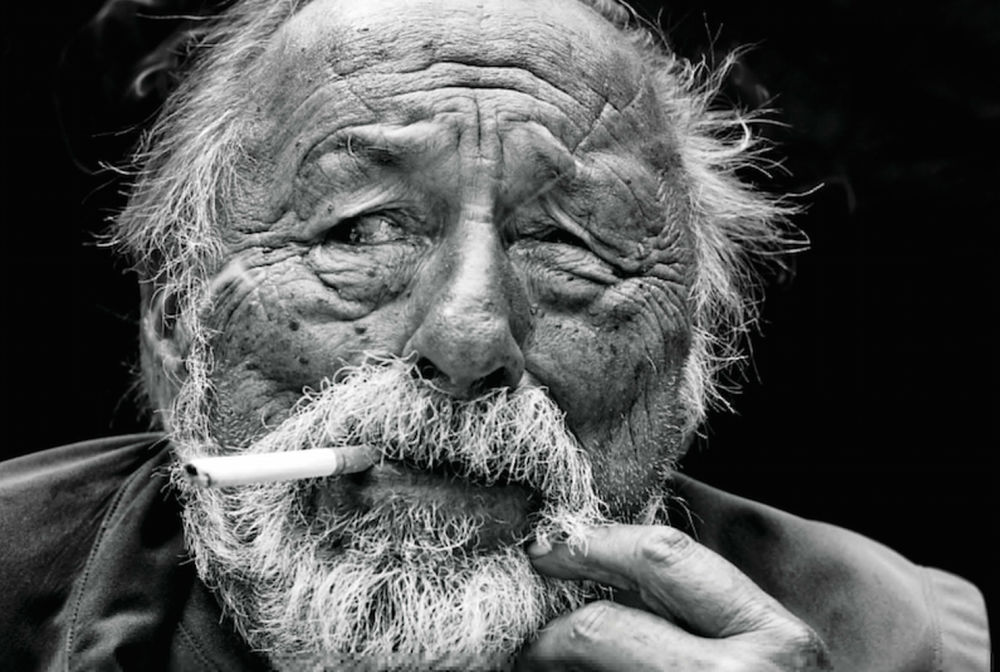

Photo by Andy Anderson

Photo by Andy Anderson

This interview was conducted over a five-day period in mid-October of 1986 at Jim Harrison’s farm in Leelanau County, Michigan. It was the middle of the bird-hunting season, and his friends, painter Russell Chatham and writer Guy de la Valdene, were staying with the Harrisons, as they have every fall for the past thirteen years. Harrison chose this particular time for the interview because it was essentially his only free time of the year, and because, as he put it, it is a time when he “tends to be intensely voluble and cheerful.” Both Harrison and his wife of twenty-seven years, Linda, are accomplished cooks, as are Chatham and de la Valdene, and this is also, it must be said, a fattening time. An enormous portion of each day is devoted to planning, shopping for, preparing, discussing, and finally eating one breathtaking meal after another, at the end of which preliminary discussions and preparations for the next meal begin almost immediately.

A threatening sign outside—DO NOT ENTER THIS DRIVEWAY UNLESS YOU HAVE CALLED FIRST. THIS MEANS YOU—is belied by the inside of the farmhouse, a hospitable home with bookcases lining the walls, dogs and cats comfortably reclined on the furniture. I arrived in the evening, just in time to participate in a dinner party for twelve, so there was even more activity in the kitchen—the soul of the house—than usual; a lot of tasting from saucepans by guests and chefs alike, a certain amount of pilferage off the butcher block countertops by the pets, and much good-natured squabbling, giving of orders, and unsolicited cooking advice, mostly ignored. There is a brief uproar when Harrison discovers that someone has tampered with his game sauce; he demands to know who and why. For dinner we are being served an appetizer of woodcock, with grouse as an entree, as well as sundry side dishes, including marvelous garlic mashed potatoes, for which Linda has poached thirty cloves of garlic in butter.

Jim Harrison is a dark-skinned, robust man, with a Pancho Villa–style moustache—oddly Latin in appearance, although he is of Scandinavian heritage. He’s been described as looking like a block layer (which he indeed was), a beer salesman, and a sumo wrestler; he bears himself with a most unique kind of physical grace, indescribable except to say that it has something to do with a style of movement that is not precisely linear. His eye—blinded in a childhood accident—is sighted off on a different plane, increasing the feeling that Harrison is a man with his own unique sense of balance.

Harrison is the author of seven books of fiction, including the novels Dalva (1988), Sundog (1984), and Wolf (1971), and the collection of novellas Legends of the Fall (1979); but he began writing as a poet, and has published six collections of poetry, most recently The Theory and Practice of Rivers and Other Poems (1986).

Because he prefers to be on the move, out of a total of almost fifteen hours of taped conversation only about two hours’ worth was conducted in any kind of a formal interview fashion—seated in Harrison’s office, a converted granary near the house, or at my room in a nearby lodge on Lake Michigan, a room in which he had written much of Legends of the Fall. The rest was conducted informally, in conversation with the tape recorder running while touring the northern Michigan countryside in his car, or walking through the woods and fields with his bird dogs. Sometimes he carried a shotgun, although considerably more talking was done than hunting.

Conversing with the poet-novelist is somehow akin to watching his dogs work the cover for birds. They race off on tangents, describing broad loops and arcs, or tight circles, always returning in a controlled, if circuitous, pattern that is at once instinct, training, ritual, and play.

Harrison is a man of prodigious memory and free-wheeling brilliance and erudition, as well as great spirit and generosity, lightness and humor; so the reader should imagine wild giggles and laughter throughout, and supply them even when they seem inappropriate—especially when they seem inappropriate. Imagine, too, the sounds and the textures in the background of the tapes: the easy talk of friends and hunting cronies; the light, cold drizzle of the wettest fall in Michigan history; sodden leaves and branches underfoot; and always the ringing of the dogs’ bells, sometimes nearby, sometimes barely discernible, fading into the woods.

A final editing of this interview was accomplished over a two-day period at his publisher’s house in Key West, Florida, where Harrison, with his family, was taking a much-needed ten-day break from work on his novel Dalva.

JIM HARRISON

I wrote this in my notebook: “My favorite moment in life is when I give my dog a fresh bone.” That comes from being the blinded seven year old hiding out in the shrubbery with his dog, whom he recognized as his true friend.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think your childhood accident when you lost sight in one eye gave you a different way of looking at things?

HARRISON

Probably. I understand they believe that in other cultures, especially when it’s the left eye.

INTERVIEWER

You seem to have a remarkable memory for the events of your childhood, which you use a lot in your work.

HARRISON

It’s nondiscriminate and that’s why you have to work hard at it. In terms of classic Freudianism, if you have a knot in your past that stops the flow of your life, it’s a psychic impediment. Your memories enlarge in ways proportionally to how willing you are to allow them to enlarge.

INTERVIEWER

Do you believe that a good memory is an essential attribute for a writer because it gives one a deeper well to draw from?

HARRISON

Sometimes I wish I could forget more things. I have to make a conscious effort to free my mind, open it again, because memory can be tremendously rapacious. Was it to you that I said jokingly that I had to go out and collect some new memories, I’m going dry? That’s why I like movement.

INTERVIEWER

This idea of movement and the metaphor of the river, seem to be central to your work.

HARRISON

It’s the origin of the thinking behind The Theory and Practice of Rivers. In a life properly lived, you’re a river. You touch things lightly or deeply; you move along because life herself moves, and you can’t stop it; you can’t figure out a banal game plan applicable to all situations; you just have to go with the “beingness” of life, as Rilke would have it. In Sundog, Strang says a dam doesn’t stop a river, it just controls the flow. Technically speaking, you can’t stop one at all.

INTERVIEWER

But you have to work at it, make a conscious effort so that your life flows like a river?

HARRISON

Antaeus magazine wanted me to write a piece for their issue about nature. I told them I couldn’t write about nature but that I’d write them a little piece about getting lost and all the profoundly good aspects of being lost—the immense fresh feeling of really being lost. I said there that my definition of magic in the human personality, in fiction and in poetry, is the ultimate level of attentiveness. Nearly everyone goes through life with the same potential perceptions and baggage, whether it’s marriage, children, education, or unhappy childhoods, whatever; and when I say attentiveness I don’t mean just to reality, but to what’s exponentially possible in reality. I don’t think, for instance, that Márquez is pushing it in One Hundred Years of Solitude—that was simply his sense of reality. The critics call this magic realism, but they don’t understand the Latin world at all. Just take a trip to Brazil. Go into the jungle and take a look around. This old Chippewa I know—he’s about seventy-five years old—said to me, “Did you know that there are people who don’t know that every tree is different from every other tree?” This amazed him. Or don’t know that a nation has a soul as well as a history, or that the ground has ghosts that stay in one area. All this is true, but why are people incapable of ascribing to the natural world the kind of mystery that they think they are somehow deserving of but have never reached? This attentiveness is your main tool in life, and in fiction, or else you’re going to be boring. As Rimbaud said, which I believed very much when I was nineteen and which now I’ve come back to, for our purposes as artists, everything we are taught is false—everything.

INTERVIEWER

How did you think at age fourteen that you might want to be a poet?

HARRISON

Those years—fourteen, fifteen, sixteen—are a vital time in anybody’s life, also a tormenting time. I wanted to be a preacher for a while, but then it seemed to me that whatever intelligence I had wouldn’t allow it. That again would be a question of leaving out the evidence. So I think all my religious passions adapted themselves to art as a religion.

INTERVIEWER

Did you always read a lot?

HARRISON

Yes. My father was a prodigious reader and passed on the habit. He was an agriculturist but he also read all of Hemingway and Faulkner and Erskine Caldwell. He read indiscriminately. Both my parents did.

INTERVIEWER

That had to have been valuable training for you.

HARRISON

A large part of writing is a recognition factor, to have read enough to know what good writing is. Finally, what Wallace Stevens said, which I love and which is hard to explain to younger writers, is that technique is the proof of your seriousness.