Issue 128, Fall 1993

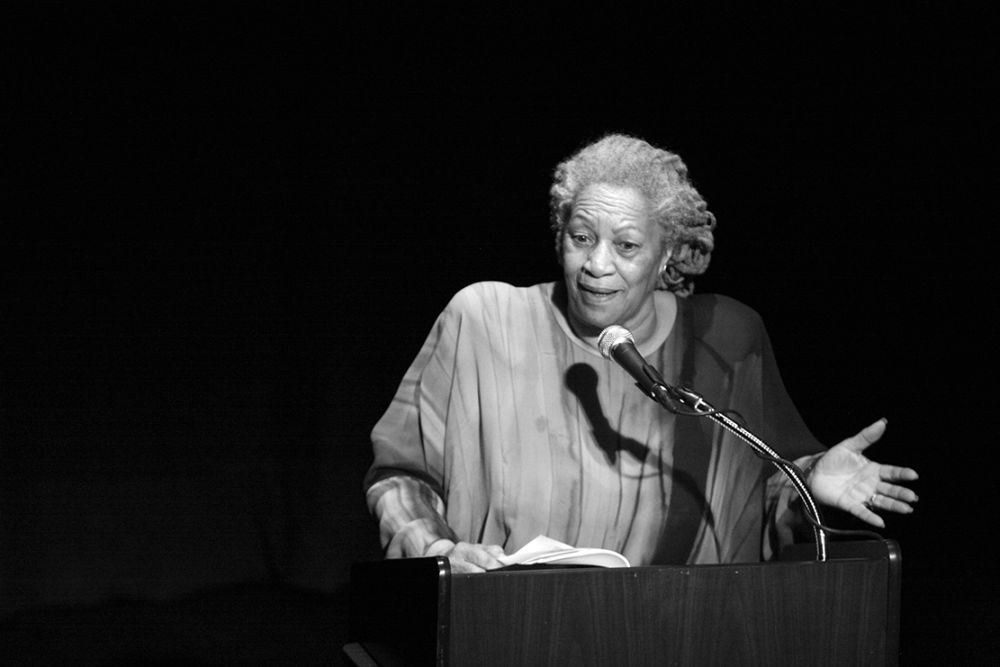

Toni Morrison, ca. 2008. Photograph by Angela Radulescu

Toni Morrison, ca. 2008. Photograph by Angela Radulescu

Toni Morrison detests being called a “poetic writer.” She seems to think that the attention that has been paid to the lyricism of her work marginalizes her talent and denies her stories their power and resonance. As one of the few novelists whose work is both popular and critically acclaimed, she can afford the luxury of choosing what praise to accept. But she does not reject all classifications, and, in fact, embraces the title “black woman writer.” Her ability to transform individuals into forces and idiosyncrasies into inevitabilities has led some critics to call her the “D. H. Lawrence of the black psyche.” She is also a master of the public novel, examining the relationships between the races and sexes and the struggle between civilization and nature, while at the same time combining myth and the fantastic with a deep political sensitivity.

We talked with Morrison one summer Sunday afternoon on the lush campus of Princeton University. The interview took place in her office, which is decorated with a large Helen Frankenthaler print, pen-and-ink drawings an architect did of all the houses that appear in her work, photographs, a few framed book-jacket covers, and an apology note to her from Hemingway—a forgery meant as a joke. On her desk is a blue glass teacup emblazoned with the likeness of Shirley Temple filled with the number two pencils that she uses to write her first drafts. Jade plants sit in a window and a few more potted plants hang above. A coffeemaker and cups are at the ready. Despite the high ceilings, the big desk, and the high-backed black rocking chairs, the room had the warm feeling of a kitchen, maybe because talking to Morrison about writing is the intimate kind of conversation that often seems to happen in kitchens; or perhaps it was the fact that as our energy started flagging she magically produced mugs of cranberry juice. We felt that she had allowed us to enter into a sanctuary, and that, however subtly, she was completely in control of the situation.

Outside, high canopies of oak leaves filtered the sunlight, dappling her white office with pools of yellowy light. Morrison sat behind her big desk, which despite her apologies for the “disorder” appeared well organized. Stacks of books and piles of paper resided on a painted bench set against the wall. She is smaller than one might imagine, and her hair, gray and silver, is woven into thin steel-colored braids that hang just at shoulder length. Occasionally during the interview Morrison let her sonorous, deep voice break into rumbling laughter and punctuated certain statements with a flat smack of her hand on the desktop. At a moment’s notice she can switch from raging about violence in the United States to gleefully skewering the hosts of the trash TV talk shows through which she confesses to channel surfing sometimes late in the afternoon if her work is done.

INTERVIEWER

You have said that you begin to write before dawn. Did this habit begin for practical reasons, or was the early morning an especially fruitful time for you?

TONI MORRISON

Writing before dawn began as a necessity—I had small children when I first began to write and I needed to use the time before they said, Mama—and that was always around five in the morning. Many years later, after I stopped working at Random House, I just stayed at home for a couple of years. I discovered things about myself I had never thought about before. At first I didn’t know when I wanted to eat, because I had always eaten when it was lunchtime or dinnertime or breakfast time. Work and the children had driven all of my habits . . . I didn’t know the weekday sounds of my own house; it all made me feel a little giddy.

I was involved in writing Beloved at that time—this was in 1983—and eventually I realized that I was clearer-headed, more confident and generally more intelligent in the morning. The habit of getting up early, which I had formed when the children were young, now became my choice. I am not very bright or very witty or very inventive after the sun goes down.

Recently I was talking to a writer who described something she did whenever she moved to her writing table. I don’t remember exactly what the gesture was—there is something on her desk that she touches before she hits the computer keyboard—but we began to talk about little rituals that one goes through before beginning to write. I, at first, thought I didn’t have a ritual, but then I remembered that I always get up and make a cup of coffee while it is still dark—it must be dark—and then I drink the coffee and watch the light come. And she said, Well, that’s a ritual. And I realized that for me this ritual comprises my preparation to enter a space that I can only call nonsecular . . . Writers all devise ways to approach that place where they expect to make the contact, where they become the conduit, or where they engage in this mysterious process. For me, light is the signal in the transition. It’s not being in the light, it’s being there before it arrives. It enables me, in some sense.

I tell my students one of the most important things they need to know is when they are their best, creatively. They need to ask themselves, What does the ideal room look like? Is there music? Is there silence? Is there chaos outside or is there serenity outside? What do I need in order to release my imagination?

INTERVIEWER

What about your writing routine?

MORRISON

I have an ideal writing routine that I’ve never experienced, which is to have, say, nine uninterrupted days when I wouldn’t have to leave the house or take phone calls. And to have the space—a space where I have huge tables. I end up with this much space [she indicates a small square spot on her desk] everywhere I am, and I can’t beat my way out of it. I am reminded of that tiny desk that Emily Dickinson wrote on and I chuckle when I think, Sweet thing, there she was. But that is all any of us have: just this small space and no matter what the filing system or how often you clear it out—life, documents, letters, requests, invitations, invoices just keep going back in. I am not able to write regularly. I have never been able to do that—mostly because I have always had a nine-to-five job. I had to write either in between those hours, hurriedly, or spend a lot of weekend and predawn time.

INTERVIEWER

Could you write after work?

MORRISON

That was difficult. I’ve tried to overcome not having orderly spaces by substituting compulsion for discipline, so that when something is urgently there, urgently seen or understood, or the metaphor was powerful enough, then I would move everything aside and write for sustained periods of time. I’m talking to you about getting the first draft.

INTERVIEWER

You have to do it straight through?

MORRISON

I do. I don’t think it’s a law.

INTERVIEWER

Could you write on the bottom of a shoe while riding on a train like Robert Frost? Could you write on an airplane?

MORRISON

Sometimes something that I was having some trouble with falls into place, a word sequence, say, so I’ve written on scraps of paper, in hotels on hotel stationery, in automobiles. If it arrives you know. If you know it really has come, then you have to put it down.

INTERVIEWER

What is the physical act of writing like for you?

MORRISON

I write with a pencil.

INTERVIEWER

Would you ever work on a word processor?

MORRISON

Oh, I do that also, but that is much later when everything is put together. I type that into a computer and then I begin to revise. But everything I write for the first time is written with a pencil, maybe a ballpoint if I don’t have a pencil. I’m not picky, but my preference is for yellow legal pads and a nice number two pencil.