Issue 128, Fall 1993

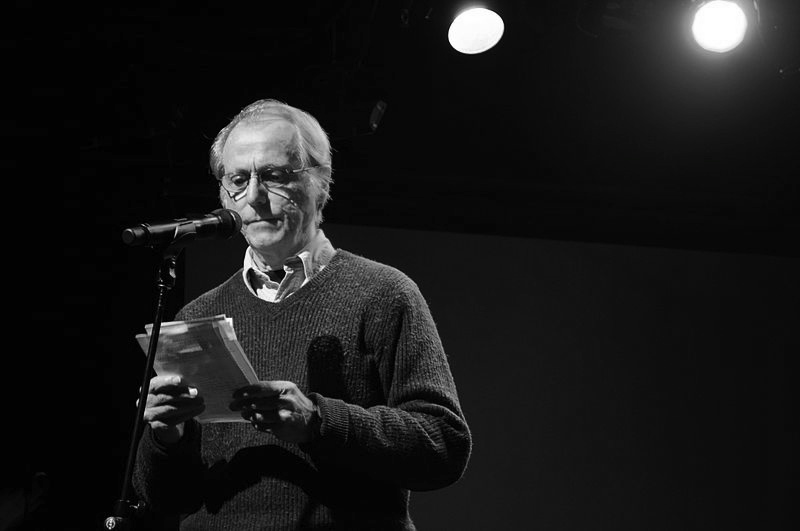

Don DeLillo, ca. 2011. Photograph by Thousandrobots

Don DeLillo, ca. 2011. Photograph by Thousandrobots

A man who’s been called “the chief shaman of the paranoid school of American fiction” can be expected to act a little nervous.

I met Don DeLillo for the first time in an Irish restaurant in Manhattan, for a conversation he said would be “deeply preliminary.” He is a slender man, gray haired, with boxy brown glasses. His eyes, magnified by thick lenses, are restless without being shifty. He looks to the right, to the left; he turns his head to see what’s behind him.

But his edgy manner has nothing to do with anxiety. He’s a disciplined observer searching for details. I also discovered after many hours of interviewing spread out over several days—a quick lunch, a visit some months later to a midtown gallery to see an Anselm Kiefer installation, followed by a drink at a comically posh bar—that DeLillo is a kind man, generous and thoughtful, qualities incompatible with the reflexive wariness of the paranoid. He is not scared; he is attentive. His smile is shy, his laugh sudden.

Don DeLillo’s parents came to America from Italy. He was born in the Bronx in 1936 and grew up there, in an Italian-American neighborhood. He attended Cardinal Hayes High School and Fordham University, where he majored in “communication arts,” and worked for a time as a copywriter at Ogilvy & Mather, an advertising agency. He now lives just outside New York City with his wife.

Americana, his first novel, was published in 1971. It took him about four years to write. At the time he was living in a small studio apartment in Manhattan. After Americana the novels poured out in a rush: five more in the next seven years. End Zone (1972), Great Jones Street(1973), Ratner’s Star (1976), Players (1977), and Running Dog (1978) all received enthusiastic reviews. They did not sell well. The books were known to a small but loyal following.

Things changed in the eighties. The Names (1982) was more prominently reviewed than any previous DeLillo novel. White Noise (1985) won the National Book Award. Libra (1988) was a bestseller. Mao II, his latest, won the 1992 PEN/Faulkner Award. He is currently at work on a novel, a portion of which appeared in Harper’s under the title “Pafko at the Wall.” He has written two plays, The Engineer of Moonlight (1979) and The Day Room (1986).

This interview began in the fall of 1992 as a series of tape-recorded conversations. Transcripts were made from eight hours of taped material. DeLillo returned the final, edited manuscript with a note that begins, “This is not only the meat but the potatoes.”

INTERVIEWER

Do you have any idea what made you a writer?

DON DeLILLO

I have an idea but I’m not sure I believe it. Maybe I wanted to learn how to think. Writing is a concentrated form of thinking. I don’t know what I think about certain subjects, even today, until I sit down and try to write about them. Maybe I wanted to find more rigorous ways of thinking. We’re talking now about the earliest writing I did and about the power of language to counteract the wallow of late adolescence, to define things, define muddled experience in economical ways. Let’s not forget that writing is convenient. It requires the simplest tools. A young writer sees that with words and sentences on a piece of paper that costs less than a penny he can place himself more clearly in the world. Words on a page, that’s all it takes to help him separate himself from the forces around him, streets and people and pressures and feelings. He learns to think about these things, to ride his own sentences into new perceptions. How much of this did I feel at the time? Maybe just an inkling, an instinct. Writing was mainly an unnameable urge, an urge partly propelled by the writers I was reading at the time.

INTERVIEWER

Did you read as a child?

DeLILLO

No, not at all. Comic books. This is probably why I don’t have a storytelling drive, a drive to follow a certain kind of narrative rhythm.

INTERVIEWER

As a teenager?

DeLILLO

Not much at first. Dracula when I was fourteen. A spider eats a fly, and a rat eats the spider, and a cat eats the rat, and a dog eats the cat, and maybe somebody eats the dog. Did I miss one level of devouring? And yes, the Studs Lonigan trilogy, which showed me that my own life, or something like it, could be the subject of a writer’s scrutiny. This was an amazing thing to discover. Then, when I was eighteen, I got a summer job as a playground attendant—a parkie. And I was told to wear a white T-shirt and brown pants and brown shoes and a whistle around my neck—which they provided, the whistle. But I never acquired the rest of the outfit. I wore blue jeans and checkered shirts and kept the whistle in my pocket and just sat on a park bench disguised as an ordinary citizen. And this is where I read Faulkner, As I Lay Dying and Light in August. And got paid for it. And then James Joyce, and it was through Joyce that I learned to see something in language that carried a radiance, something that made me feel the beauty and fervor of words, the sense that a word has a life and a history. And I’d look at a sentence in Ulysses or in Moby-Dick or in Hemingway—maybe I hadn’t gotten to Ulysses at that point, it was Portrait of the Artist—but certainly Hemingway and the water that was clear and swiftly moving and the way the troops went marching down the road and raised dust that powdered the leaves of the trees. All this in a playground in the Bronx.

INTERVIEWER

Does the fact that you grew up in an Italian-American household translate in some way, does it show up in the novels you’ve published?

DeLILLO

It showed up in early short stories. I think it translates to the novels only in the sense that it gave me a perspective from which to see the larger environment. It’s no accident that my first novel was called Americana. This was a private declaration of independence, a statement of my intention to use the whole picture, the whole culture. America was and is the immigrant’s dream, and as the son of two immigrants I was attracted by the sense of possibility that had drawn my grandparents and parents. This was a subject that would allow me to develop a range I hadn’t shown in those early stories—a range and a freedom. And I was well into my twenties by this point and had long since left the streets where I’d grown up. Not left them forever—I do want to write about those years. It’s just a question of finding the right frame.

INTERVIEWER

What got you started on Americana?

DeLILLO

I don’t always know when or where an idea first hits the nervous system, but I remember Americana. I was sailing in Maine with two friends, and we put into a small harbor on Mt. Desert Island. And I was sitting on a railroad tie waiting to take a shower, and I had a glimpse of a street maybe fifty yards away and a sense of beautiful old houses and rows of elms and maples and a stillness and wistfulness—the street seemed to carry its own built-in longing. And I felt something, a pause, something opening up before me. It would be a month or two before I started writing the book and two or three years before I came up with the title Americana, but in fact it was all implicit in that moment—a moment in which nothing happened, nothing ostensibly changed, a moment in which I didn’t see anything I hadn’t seen before. But there was a pause in time, and I knew I had to write about a man who comes to a street like this or lives on a street like this. And whatever roads the novel eventually followed, I believe I maintained the idea of that quiet street if only as counterpoint, as lost innocence.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think it made a difference in your career that you started writing novels late, when you were approaching thirty?

DeLILLO

Well, I wish I had started earlier, but evidently I wasn’t ready. First, I lacked ambition. I may have had novels in my head but very little on paper and no personal goals, no burning desire to achieve some end. Second, I didn’t have a sense of what it takes to be a serious writer. It took me a long time to develop this. Even when I was well into my first novel I didn’t have a system for working, a dependable routine. I worked haphazardly, sometimes late at night, sometimes in the afternoon. I spent too much time doing other things or nothing at all. On humid summer nights I tracked horseflies through the apartment and killed them—not for the meat but because they were driving me crazy with their buzzing. I hadn’t developed a sense of the level of dedication that’s necessary to do this kind of work.

INTERVIEWER

What are your working habits now?

DeLILLO

I work in the morning at a manual typewriter. I do about four hours and then go running. This helps me shake off one world and enter another. Trees, birds, drizzle—it’s a nice kind of interlude. Then I work again, later afternoon, for two or three hours. Back into book time, which is transparent—you don’t know it’s passing. No snack food or coffee. No cigarettes—I stopped smoking a long time ago. The space is clear, the house is quiet. A writer takes earnest measures to secure his solitude and then finds endless ways to squander it. Looking out the window, reading random entries in the dictionary. To break the spell I look at a photograph of Borges, a great picture sent to me by the Irish writer Colm Tóibín. The face of Borges against a dark background—Borges fierce, blind, his nostrils gaping, his skin stretched taut, his mouth amazingly vivid; his mouth looks painted; he’s like a shaman painted for visions, and the whole face has a kind of steely rapture. I’ve read Borges of course, although not nearly all of it, and I don’t know anything about the way he worked—but the photograph shows us a writer who did not waste time at the window or anywhere else. So I’ve tried to make him my guide out of lethargy and drift, into the otherworld of magic, art, and divination.