Issue 131, Summer 1994

Photo: George McClintock.

Photo: George McClintock.

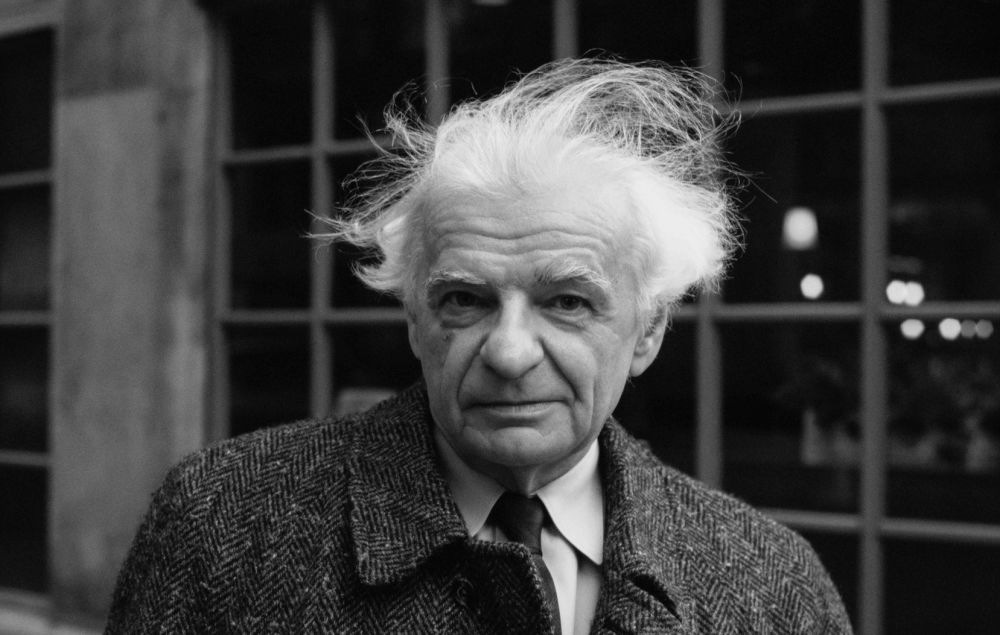

Yves Bonnefoy works in a tiny apartment in Montmartre, a few steps from where he lives. His windows at the back look over a small garden, one of the few remaining parts of Montemartre that has not been built upon—a huge maple tree shades the building and the rose-covered walls. The apartment is jam-packed with books and tables, the largest of which is the poet’s desk, so crowded that it hides him almost completely from view. A small, worm-eaten statue of Sainte Barbe, “early seventeenth-century”, a Giacometti lithograph of his wife Annette, an oil painting depicting Verlaine, Rimbaud, and Mathilde Mauté (Verlaine’s wife), and photographs of Rimbaud and Baudelaire somehow find space on the walls and in niches among the floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. “I cross the road every morning to try and work here quietly,” he explains.

Yves Bonnefoy was born on June 24, 1923 in Tours. He studied mathematics, the history of science, and philosophy at the University of Poitiers and the Sorbonne. Later he worked for three years at the National Center for Scientific Research before devoting himself completely to writing and lecturing.

Bonnefoy’s first book of poems, On the Motion and Immobility of Douve, was published in 1953 and won him immediate recognition as a new, major voice. Three other books appeared at irregular intervals and were collected in one volume under the title of Poèmes. In 1987 he published In the Shadow’s Light, followed by Début et fin de la neige in 1991. Today he is acknowledged as the most outstanding and influential poet in France today.

Since 1954 Bonnefoy has also produced many works of literary and art criticism—Rimbaud, Un rêve fait à Mantoue, Rome 1630, Entretiens sur la poésie (Dialogues on Poetry). His translations of Shakespeare’s plays are considered the best to date, and two years ago he published his translation of some fifty poems by Yeats.

Over the past thirty years Bonnefoy has been a regular visitor to universities in the United States as professor of literature and lecturer, while holding occasional teaching posts at French universities as well. Since 1981 he has been the professor of comparative poetics at the Collège de France. He is the director of the collection Idées et Recherches at Flammarion, and the editor of Mythologies, now published in English by the University of Chicago Press. He is married to American painter Lucy Vines, and they have one daughter, Mathilde.

Last fall the Bibliothèque Nationale honored the poet with a large comprehensive exhibition of his manuscripts, first editions, and pictures.

With characteristic generosity Yves Bonnefoy devoted many hours to the following interview, which took place in June of 1992 in his study. A year later another session, this time with a particular emphasis on his books written in collaborations with painters and on his writing about art, took place at the Château de Tours.

INTERVIEWER

You were born on midsummer night in Tours, where the most beautiful French is said to be spoken, in a region that was the birthplace of Ronsard, one of French poetry’s founding fathers. Did you ever live there?

YVES BONNEFOY

Yes, up to the age of twenty; then I hardly ever returned, except to visit my mother who lived there until her death. Lately I have had reasons to renew my visits.

INTERVIEWER

Your father was a railway man and your mother a schoolteacher. Were they interested in culture? Because the equivalent milieu in England is not.

BONNEFOY

Not especially. My father’s parents were innkeepers near the valley of the Lot River. Theirs was a little place near the railway station, with a few rooms they let. My grandmother cooked, and my grandfather looked after the clients. He also cut hair and made jackets. One day some priests were passing through the village, and they asked if anybody had a little boy whom they could take and educate well, and who would perhaps accept later to become a priest. My grandfather gave them my father, whom they took with them to the seminary at Rocamadour.

After a couple of years my father, who did not like studying, ran away. His father was angry and said to him that if he didn’t want to study he should look after himself. So he left home and became an apprentice to a blacksmith relative. After his quite long military service he went to work in the workshop of the railways, building locomotives. He worked hard, especially during World War I, and was rather poor. I don’t think he had any time for culture.

My mother’s father was a schoolteacher. He did aspire to culture; he had built a little pinewood desk at which he wrote all sorts of books that he bound himself—a treatise on history, and one on morals—just for the pleasure of writing. Perhaps he had the illusion that he was a writer and one day would be published. I have kept some of his manuscripts. They contain a great variety of things, for example drawings of plants and flowers, and a study of geometrical perspective. He was not religious, yet he wrote a small book on religious instruction and sacred history, “Love of One’s Neighbor,” which I suppose was his way of accepting the priest who was his neighbor.

He wanted his two daughters to be schoolteachers. My aunt was rather intellectual and accepted, but my mother became seriously ill at fifteen, which interrupted her studies. So she decided to be a nurse, which was very frowned upon in those days. She worked as a nurse during the war, after having married my father and later became an institutrice—a primary school teacher.

My father died when I was thirteen. By then my grandfather was also dead, but the latter was certainly an important influence in my life—this old man who had books, who thought, read, and wrote, created an example and a reference for me. Today a child of such a milieu would perhaps not have the same access to culture and to cultivated society as I did; the education system was very good and efficient then—we had excellent state primary schools where we learned things, while today, especially in poor neighborhoods, it’s all rowdiness and heckling. My grandfather himself owed his career to the fact that school had become compulsory in his time, as his mother was an unmarried shepherdess who looked after pigs in the local oakwoods, and would have been unable to do anything for her son. But he got a prize because he received the best grades on his exams of the students in all the schools of the region, and then a grant to a teacher’s training college, and then became a teacher. One could say that he was “a son of the Rights of Man,” as Rimbaud said, which proclaims that all men have a right to education, therefore to primary school. After the school certificate I myself entered a competition and obtained a grant to continue studying at the Lycée Descartes in Tours. Today there are too many students in the classrooms, but then we learned Latin and read books.

INTERVIEWER

What did you do after the lycée?

BONNEFOY

I entered one of those special classes that prepare pupils for the entrance exam of the grandes écoles, scientific or literary. I chose the scientific alternative, while simultaneously doing a degree in mathematics at the University of Poitiers. Then I realized that the grandes écoles destined you for the sort of profession—engineering, mining, mathematics teaching—which I had no wish to pursue, for I already had an idea of what I did want to do with my life—to write. So I came up to Paris, supposedly to finish my degree in mathematics, but in fact to find the surrealist milieu. At the lycée in Tours I had learned about surrealism and read André Breton.

INTERVIEWER

When you decided to be a writer did you intend to be a poet?

BONNEFOY

I still have a little anthology of poems that my aunt gave me, perhaps for my seventh birthday, in which she has inscribed “to my godson—future poet.” There was no mystery: even before I learned to read and write I knew it was in order to write poetry. Why? Perhaps because of a feeling that I could not practice the professions I saw around me.

INTERVIEWER

During adolescence did you read much poetry? Or write any?

BONNEFOY

I started reading poetry in primary school—Victor Hugo, the romantics, and the Parnassians—they were part of the curriculum. In my grandfather’s library there were some anthologies of nineteenth-century poetry. Alfred de Vigny impressed me most; indeed I won a competition by reciting Vigny’s “Moses” with an enthusiasm that touched the examiner. In fact this poem and “La Maison du Berger” are among the most beautiful poems in the French language, unfairly neglected today.

INTERVIEWER

What about the Parnassians? Which ones impressed you?

BONNEFOY

I was not much taken by their poems, but I liked Leconte de Lisle’s translation of Homer, especially his Iliad, which brought me the classical world. I have often felt a great difference between myself and the next generation, those who were twenty in 1950, although it is only a few years, because I had read in my grandfather’s library books that were later less accessible. The next generation was reading Michaux, Prévert, Éluard—twentieth-century authors. I’m glad to have read the Greek classics, and French ones too—writers like Racine and Corneille.

INTERVIEWER

When did you read Baudelaire and Rimbaud—poets whose influence on your own work is strongly felt?

BONNEFOY

When you have only a few books, anthologies are in the forefront. When I was fourteen or fifteen I read Towards a Lyrical Alchemy, in which I found poems by Baudelaire, Nerval, Sainte-Beuve—the beautiful poems of early modernity. Later I read Valéry for a while. I was not the only one to be taken by Valéry—it was a phenomenon of the era. When I arrived in Paris in November of 1943 I rushed to hear Valéry’s lectures at the Collège de France. We were not many in the auditorium, and I did not know anyone. Later I discovered that Cioran and Roland Barthes were there too. We were all fascinated by Valéry, though he was not an interesting lecturer—perhaps because he was already rather worn out, ill, or perhaps because he was not interested in other poets’ works, though they’re rather useful if one has accepted the responsibility of twenty-six hours of teaching per year! One can’t speak that long about oneself, even if one is le témoin du moi [the witness to oneself], which he wanted to be. Still, I admired him, and I still love some of his poems, especially “Le Cimetière marin”, which is beautiful. Then I rebelled and wrote an incendiary essay about him, “Paul Valéry the Apostate”—meaning apostasy against poetry. It has been reprinted in my book of essays L’Improbable.

Cioran did the same thing a few years later when he was asked to write a preface for the American publication of The Collected Works of Paul Valéry, edited by Jackson Mathews. As he wrote he felt his anger growing, and the text was so vitriolic that of course the publishers rejected it.