Issue 137, Winter 1995

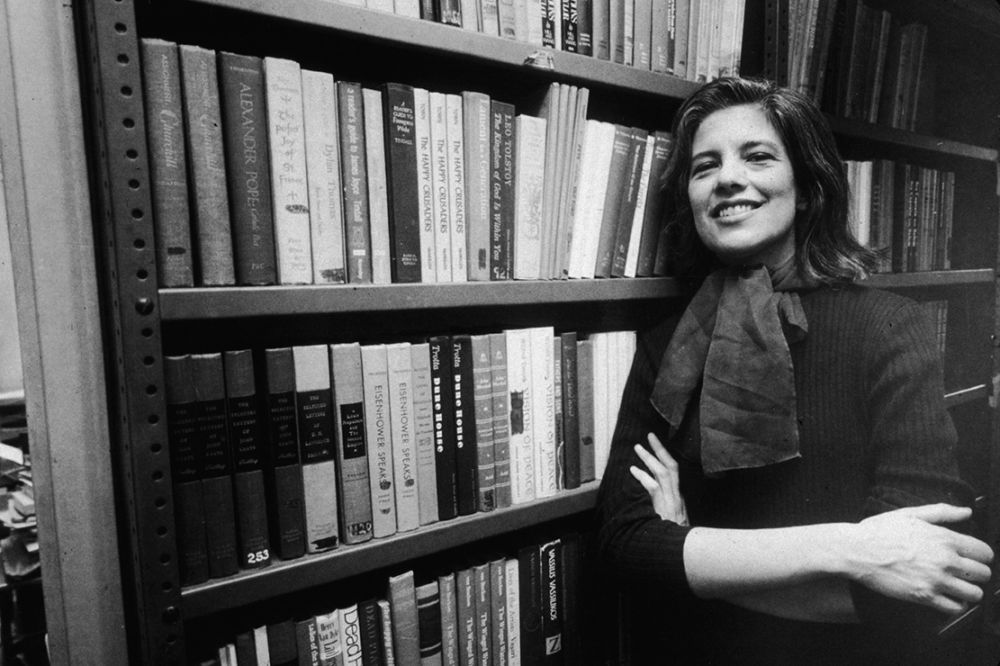

Susan Sontag lives in a sparsely furnished five-room apartment on the top floor of a building in Chelsea on the west side of Manhattan. Books—as many as fifteen thousand—and papers are everywhere. A lifetime could be spent browsing through the books on art and architecture, theater and dance, philosophy and psychiatry, the history of medicine, and the history of religion, photography, and opera—and so on. The various European literatures—French, German, Italian, Spanish, Russian, etcetera, as well as hundreds of books of Japanese literature and books on Japan—are arranged by language in a loosely chronological way. So is American literature as well as English literature, which runs from Beowulf to, say, James Fenton. Sontag is an inveterate clipper, and the books are filled with scraps of paper (“Each book is marked and filleted,” she says), the bookcases festooned with notes scrawled with the names of additional things to read.

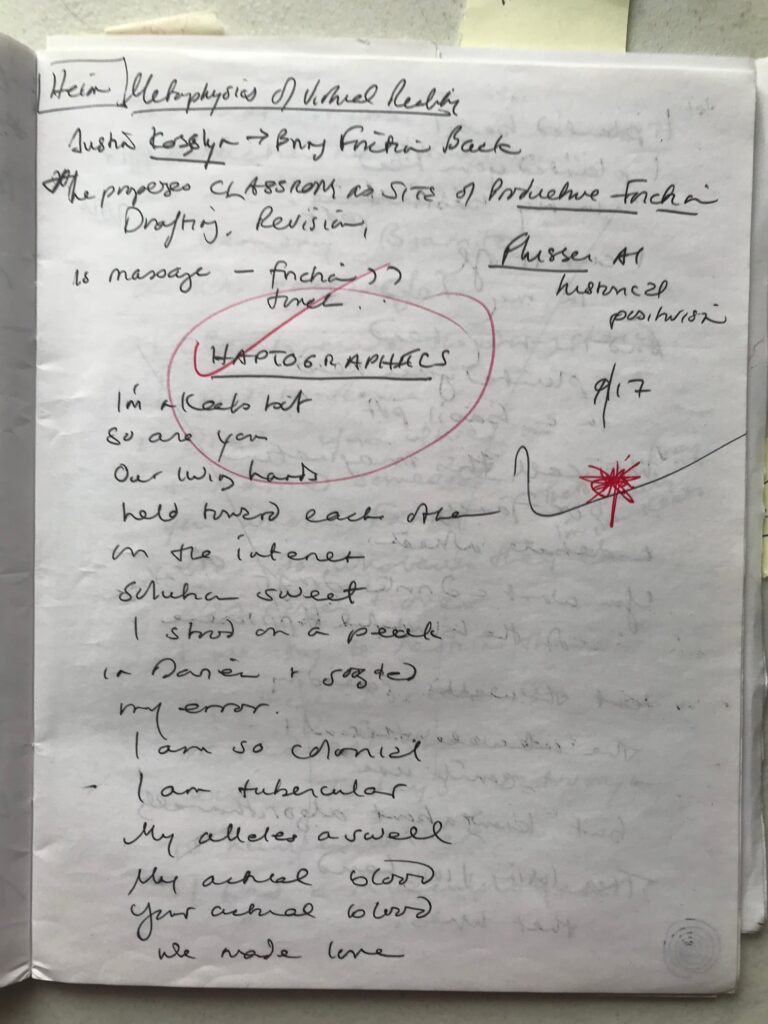

Sontag usually writes by hand on a low marble table in the living room. Small theme notebooks are filled with notes for her novel in progress, “In America.” An old book on Chopin sits atop a history of table manners. The room is lit by a lovely Fortuny lamp, or a replica of one. Piranesi prints decorate the wall (architectural prints are one of her passions).

Everything in Sontag’s apartment testifies to the range of her interests, but it is the work itself, like her conversation, that demonstrates the passionate nature of her commitments. She is eager to follow a subject wherever it leads, as far as it will go—and beyond. What she has said about Roland Barthes is true about her as well: “It was not a question of knowledge . . . but of alertness, a fastidious transcription of what could be thought about something, once it swam into the stream of attention.”

Sontag was interviewed in her Manhattan apartment on three blisteringly hot days in July of 1994. She had been traveling back and forth to Sarajevo, and it was gracious of her to set aside time for the interview. Sontag is a prodigious talker—candid, informal, learned, ardent—and each day at a wooden kitchen table held forth for seven- and eight-hour stretches. The kitchen is a mixed-use room, but the fax machine and the photocopier were silent; the telephone seldom rang. The conversation ranged over a vast array of subjects—later the texts would be scoured and revised—but always returned to the pleasures and distinctions of literature. Sontag is interested in all things concerning writing—from the mechanism of the process to the high nature of the calling. She has many missions, but foremost among them is the vocation of the writer.

INTERVIEWER

When did you begin writing?

SUSAN SONTAG

I’m not sure. But I know I was self-publishing when I was about nine; I started a four-page monthly newspaper, which I hectographed (a very primitive method of duplication) in about twenty copies and sold for five cents to the neighbors. The paper, which I kept going for several years, was filled with imitations of things I was reading. There were stories, poems and two plays that I remember, one inspired by ÄŒapek’s R.U.R., the other by Edna St. Vincent Millay’s Aria de Capo. And accounts of battles—Midway, Stalingrad, and so on; remember, this was 1942, 1943, 1944—dutifully condensed from articles in real newspapers.

INTERVIEWER

We’ve had to postpone this interview several times because of your frequent trips to Sarajevo that, you’ve told me, have been one of the most compelling experiences of your life. I was thinking how war recurs in your work and life.

SONTAG

It does. I made two trips to North Vietnam under American bombardment, the first of which I recounted in “Trip to Hanoi,” and when the Yom Kippur War started in 1973 I went to Israel to shoot a film, Promised Lands, on the front lines. Bosnia is actually my third war.

INTERVIEWER

There’s the denunciation of military metaphors in Illness as Metaphor. And the narrative climax of The Volcano Lover, a horrifying evocation of the viciousness of war. And when I asked you to contribute to a book I was editing, Transforming Vision: Writers on Art, the work you chose to write about was Goya’s The Disasters of War.

SONTAG

I suppose it could seem odd to travel to a war, and not just in one’s imagination—even if I do come from a family of travelers. My father, who was a fur trader in northern China, died there during the Japanese invasion—I was five. I remember hearing about “world war” in September 1939, entering elementary school, where my best friend in the class was a Spanish Civil War refugee. I remember panicking on December 7, 1941. And one of the first pieces of language I ever pondered over was “for the duration”—as in “there’s no butter for the duration.” I recall savoring the oddity, and the optimism, of that phrase.

INTERVIEWER

In “Writing Itself,” on Roland Barthes, you express surprise that Barthes, whose father was killed in one of the battles of the First World War (Barthes was an infant) and who, as a young man himself, lived through the Second World War—the Occupation—never once mentions the word war in any of his writings. But your work seems haunted by war.

SONTAG

I could answer that a writer is someone who pays attention to the world.

INTERVIEWER

You once wrote of Promised Lands: “My subject is war, and anything about any war that does not show the appalling concreteness of destruction and death is a dangerous lie.”

SONTAG

That prescriptive voice rather makes me cringe. But . . . yes.

INTERVIEWER

Are you writing about the siege of Sarajevo?

SONTAG

No. I mean, not yet, and probably not for a long time. And almost certainly not in the form of an essay or report. David Rieff, who is my son, and who started going to Sarajevo before I did, has published such an essay-report, a book called Slaughterhouse—and one book in the family on the Bosnian genocide is enough. So I’m not spending time in Sarajevo to write about it. For the moment it’s enough for me just to be there as much as I can—to witness, to lament, to offer a model of noncomplicity, to pitch in. The duties of a human being, one who believes in right action, not of a writer.