Issue 139, Summer 1996

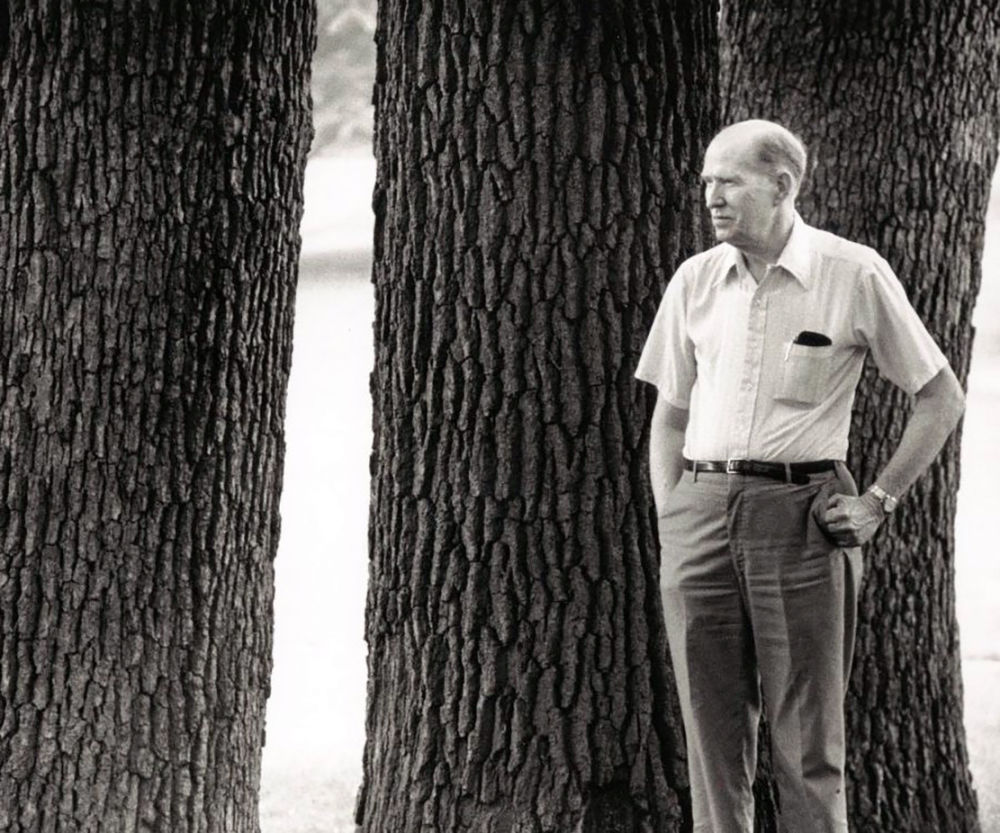

One day in the winter of 1987 Archie Ammons was driving north on the I-95 in Florida when a gigantic hill of rubble came into view. The sight sparked an epiphany: “I thought maybe that was the sacred image of our time,” the poet said. Upon his return to Ithaca, New York, where he is the Goldwin Smith Professor of Poetry at Cornell University, Ammons tried to write a long poem entitled Garbage. Nothing came of the first attempt. Two years later, however, the image returned and wouldn’t let him off so easily. He wrote the poem quickly, finished it in a season, then put it aside. A major medical predicament—a massive coronary in August 1989 and triple bypass surgery a year later—intervened. When Ammons returned to the poem, he was no longer sure of it, and when it was accepted by his publisher, he was surprised. Nobody else was when this extraordinary work went on to win the 1993 National Book Award in poetry, the second time Ammons has been so honored. Ammons received the Frost Medal from the Poetry Society of America in April 1994. Later that year, he and his wife, Phyllis, drove to Washington (the Ammonses do not believe in flying) to collect the Bobbitt Prize, which sounds like something a Court TV reporter made up but is actually an accolade bestowed by the Library of Congress.

Born in Whiteville, North Carolina, in 1926—“big, jaundiced and ugly,” in his words—Archie Randolph Ammons grew up on a family tobacco farm during the meanest years of the Great Depression. He had two sisters; one brother died as an infant, a loss mourned in his powerful poem “Easter Morning.” The hymns Archie heard every Sunday in church had their mostly unconscious influence on his poetry, which he began writing in the navy during World War II. Some of his first efforts were comic poems about shipmates aboard the destroyer escort on which he served in the South Pacific. Ammons recently wrote the poem “Ping Jockeys” when he found out that two pillars of the New York School of poets, James Schuyler and Frank O’Hara, had also been trained as sonar men on Key West, where Ammons learned “how to lay down depth-charge patterns on enemy bulks.”

Ammons got out of the navy in 1946. He was able to attend college thanks to that piece of enlightened social legislation, the G.I. Bill, which paid his way at Wake Forest College, where he began as a premed student. In a writing class taught by E. E. Folk, he learned his method of “the transforming idea”—how to organize materials gathered from disparate sources—which he has continued to use in his poems. Another course with a decisive impact on Ammons’s life was intermediate Spanish, which was taught by Phyllis Plumbo, a recent graduate of Douglass College, then the women’s division of Rutgers University. Archie walked her home one day, and the couple will soon celebrate their forty-seventh wedding anniversary.

Ammons did not enter the academic life until he was close to forty. In 1949, he became the principal of the tiny elementary school in the island village of Cape Hatteras. For most of the next decade he worked as a sales executive in his father-in-law’s biological glass company on the southern New Jersey shore. Ammons published Ommateum, his first book of poems, with Dorrance, a vanity press, in 1955; a mere sixteen copies were sold in the next five years. (A copy today would fetch two thousand dollars.) He joined the Cornell University faculty in 1964 and has taught there ever since.

Expressions of Sea Level, Ammons’s second collection, came out in 1964 from Ohio State University Press and triggered the most prolific period in his career. He went rapidly from total obscurity to wide acclaim. His prematurely entitled Collected Poems 1951–1971 won the National Book Award in 1973. He won the coveted Bollingen Prize for his long poem Sphere(1974), in which the governing image was the earth as photographed from outer space. Ammons’s method for writing a long poem is, in a nutshell, finding “a single image that can sustain multiplicity.”

For a poet who believes in inspiration and spontaneity, Ammons is a creature of fixed habit. He begins his days having coffee in the Temple of Zeus, a coffee bar on the Cornell campus, with a handful of chums such as the Nobel Prize–winning chemist and poet Roald Hoffmann. (Hoffmann, who has written three books of poems, unabashedly calls Ammons his guru.) Archie professes to despise the poetry-writing industry and has a skeptical attitude on the whole question of whether poetry can be taught. Yet his own reputation among students past and present is high. A casual exchange of poems with Archie can turn into a memorable experience. “I have coffee sometimes in the morning for years with people,” Ammons says. “And then it may be five or ten years afterwards they will show me something they’ve written and I will suddenly feel that I know them better in that minute than I have known them through all the conversations that had taken place before.”

This interview was conducted by a variety of means. We began with two long sessions with a tape recorder in Ammons’s house in Ithaca. Briefer exchanges in person, on the phone, and by mail followed at regular intervals. It was as if we were continuing a conversation that had begun in 1976, when we met, and of which this interview is a sample and a distillation. We shelved it for a while while we worked together on The Best American Poetry 1994, for which Archie made the selections, and then we picked up where we had left off.

Ammons’s twenty-third book of poems, Brink Road, was published by Norton in the spring of 1996. Set in Motion, a gathering of his prose, will appear in the Poets on Poetry Series of the University of Michigan Press.

A. R. AMMONS

Aren’t you going to start with the typical Paris Review interview question, such as, “What do you write with or on?”

INTERVIEWER

All right. [Pause.] What do you write with or on?

AMMONS

My poems begin on the typewriter. If I’m home—and I rarely write anything elsewhere—I write on an Underwood standard upright, manual, not electric, which I bought used in Berkeley in 1951 or 1952. It had been broken and was rewelded. It’s worked without almost any attention for forty-four years. When I was away a few times, for a year or a summer, I wrote on similar typewriters. It’s hard now to find regular typewriter paper (as opposed to Xerox paper) and ribbons.

I sometimes scribble words or phrases or poems with a pen and pencil if I’m traveling or at work. But I like the typewriter because it allows me to set up the shapes and control the space. Though I don’t care for much formality (in fact, I hate ceremony), I need to lend a formal cast, at least, to the motions I so much love.

INTERVIEWER

When you begin a poem, do you have a specific source of inspiration, or do you start with words and push them around the page until they begin to take shape?

AMMONS

John Ashbery says that he would never begin to write a poem under the force of inspiration or with an idea already given. He prefers to wait until he has absolutely nothing to say, and then begins to find words and to sort them out and to associate with them. He likes to have the poem occur on the occasion of its occurrence rather than to be the result of some inspiration or imposition from the outside. Now I think that’s a brilliant point of view. That’s not the way I work. I’ve always been highly energized and have written poems in spurts. From the god-given first line right through the poem. And I don’t write two or three lines and then come back the next day and write two or three more; I write the whole poem at one sitting and then come back to it from time to time over the months or years and rework it.

INTERVIEWER

Did you write, say, “The City Limits” in one sitting?

AMMONS

Absolutely.

INTERVIEWER

The eighteen lines of that poem do seem to be a single outcry. Were there changes after you wrote it?

AMMONS

Hardly a one. I sent the poem to Harold Bloom, something I almost never had done, and he admired it and sent a note to me not to change a word.

INTERVIEWER

Bloom has been a longtime champion of your work. How long have you known him?

AMMONS

He was here for the year in 1968, and his children were the same age as my son John, and they became playmates. Harold and I became friends. I didn’t regularly send him my poems, and he never suggested how they be written. But I wrote “The City Limits” and I wanted to share it with him. It was not literary business. It was friendship business. That was in 1971.

INTERVIEWER

Does inspiration originate in nature, in external reality, or in the self?

AMMONS

I think it comes from anxiety. That is to say, either the mind or the body is already rather highly charged and in need of some kind of expression, some way to crystallize and relieve the pressure. And it seems to me that if you’re in that condition and an idea, an insight, an association occurs to you, then that energy is released through the expression of that insight or idea, and after the poem is written, you feel a certain resolution and calmness. Well, I won’t say a “momentary stay against confusion” (Robert Frost’s phrase) but that’s what I mean. I think it comes from that. You know, Bloom says somewhere that poetry is anxiety.

INTERVIEWER

Bloom talks about the anxiety of influence, but you talk about the influence of anxiety.

AMMONS

Absolutely. The invention of a poem frequently is how to find a way to resolve the complications that you’ve gotten yourself into. I have a little poem about this that says that the poem begins as life does, takes on complications as novels do, and at some point stops. Something has to be invented before you can work your way out of it, and that’s what happens at the very center of a poem.

INTERVIEWER

What poem are you referring to?

AMMONS

It’s called “The Swan Ritual.” It’s in the Collected Poems.

INTERVIEWER

I have this picture of you taking long walks along places mentioned in your poems, such as Cascadilla Falls here in Ithaca or Corsons Inlet on the New Jersey shore, and writing as you were walking, writing out something longhand.

AMMONS

Or memorizing it in your head.