Issue 198, Fall 2011

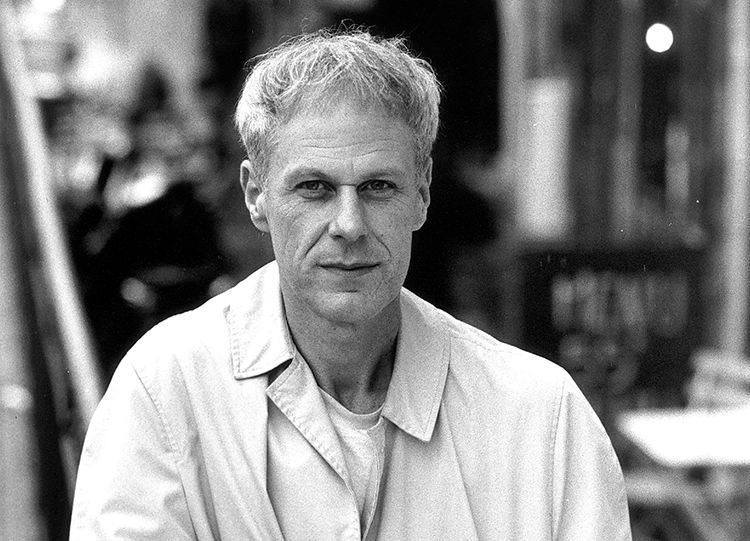

Dennis Cooper in Paris in 2005.

Dennis Cooper in Paris in 2005.

Brest sits at the westernmost point of France, and the TGV train from Paris makes the trip in just over four hours. I joined Dennis Cooper there last February. He was in Brest to oversee the premiere of his performance work, Last Spring: A Prequel—one of his collaborations with French director and puppeteer Gisèle Vienne. During Last Spring, Cooper watched quietly as a life-size boy robot named Charles pleaded for its life with the glove puppet he wore on his hand. “I don’t know how I’m here with you,” Charles says to the audience, “but I swear to fucking God, I am real. And scared shitless. Can’t you see that?! Can’t you tell?!”

Although he has lived in Paris for the past six years, Cooper was born in Pasadena, in 1953, and has spent most of his life in Los Angeles. In the mid-seventies, he made his way from the San Gabriel Valley to West Los Angeles. He became involved with the Beyond Baroque Literary/Arts Center in Venice Beach, and served as director of programming from 1979 to 1983, hosting readings and performances by Amy Gerstler, Mike Kelley, Jessica Hagedorn, Eric Bogosian, and others. He founded the literary journal Little Caesar Magazine in 1976 and, two years later, Little Caesar Press.

Cooper’s first collections of poetry, published in the seventies and early eighties by small California presses, were inspired by young male celebrities like David Cassidy and the young John Kennedy, Jr., and by high-school classmates, who loomed godlike as characters in this early work. His first book of fiction, the novella Safe, was published in 1984. That same year, he began work on the five novels that make up the George Miles Cycle. The first book of the cycle, Closer, published in 1989, earned Cooper a reputation as an important yet challenging new writer. Thomas Edwards, in The New York Review of Books, called it “a work of considerable courage.” Writing in The Washington Post Book World, the poet John Ash deemed it “a minor classic.”

Since then, Cooper’s fiction has often been associated with a generation of underground writers and artists, including Mary Gaitskill, Kathy Acker, Gary Indiana, Karen Finley, and David Wojnarowicz, known both for formal experimentation and frank treatments of sex. Although Cooper’s subject matter—in particular his interest in pornography, violent sex, and boys—has dominated American discussions of his work, the cycle, which he completed in 2000, reflects a fastidious formalism. He has found a more sympathetic reception in France, from both readers and critics, ever since his work was first translated in 1995. He is one of very few Americans published by P.O.L., a house that occupies a deeply respected place in French letters. In 2007, he became the first American to win the Prix Sade.

In the twenty-five years Cooper and I have known each other (I have been, at various times, his editor, publisher, and publicist and, since 1990, his literary agent), we have never discussed his work or life so deeply as in these conversations. We were both very nervous. We began our interview at the Hotel Vauban in Brest. We continued in Paris, in the lobby of the Relais Hotel Du Vieux Paris, once known as the Beat Hotel, haunt of Kerouac and Burroughs and Ginsberg. When we talked about his friend George Miles, Cooper broke into tears; it was the first time I had ever seen him cry.

—Ira Silverberg

INTERVIEWER

What did you read when you were a kid?

COOPER

I was into artful, challenging music and movies from a young age, but with books, I mostly read junk. I loved novelizations of TV shows. They used to put out really crappy novels, usually in series, that milked the characters and story lines of popular TV shows of that era, like Batman and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Get Smart. I was obsessed with those books. In school, I almost never read the literature we were assigned. I’d usually skip or skim the books and stories, then fake it in discussions and written reports. But then, when I was fifteen, I read an interview with Bob Dylan, and he mentioned Rimbaud. So I bought one of Rimbaud’s books, and I was staggered. Everything changed. His poetry, his biography, the fact that he wrote such incredible things and was so ambitious when he was my age were hugely inspiring, and I just dove into French literature after that, looking for other writers like him.

INTERVIEWER

What did you find?

COOPER

I started with the poets—Baudelaire, Lautréamont, Apollinaire, Reverdy. Then I found my way into the French novelists who had been translated into English, and I started reading Genet, Céline, Gide, Roussel, and on and on. The giant discovery was Sade. I found The 120 Days of Sodom at fifteen, too, and suddenly my secret investigation of disturbing, sexually charged things and my confusing fantasies were legitimized.

INTERVIEWER

What fantasies?

COOPER

For reasons I don’t understand, I had been fascinated by the axis of sex and violence for as far back as my memories went. When I was a child, I had nightmares in which that combination of impulses was paramount, and when I hit puberty, those kinds of scenarios entered my fantasy life. I found them both extremely terrifying and very exciting in equal measure.

I was riveted by real-life crimes of that nature, both in history and in the world around me, and I would obsess over them in secret, recounting them in detail as well as trying to analyze my interest in them in diaries. My very rare attempts to talk about those things with my friends were met with disgusted reactions and accusations that I was weird and sick, so I basically hid that part of myself from everyone. When I found Sade, I realized that fiction was a place I could release and formulate and try to represent that part of me, that what I had thought was some horrible aspect of me that would isolate me from the world was in fact legitimate and even an important subject matter for literature. The Grove Press editions of Sade’s books that I read had super-heady essays on and in defense of Sade’s work by Beauvoir and Blanchot, so I knew what he was doing was serious literature. Between the double mindblows of Rimbaud and Sade, I found what I wanted to do with my life. I kept reading all the avant-garde fiction I could find.

INTERVIEWER

American avant-garde as well as French?

COOPER

The American stuff came later. In my high school years, experimental American fiction was considered very cool and fashionable, and my friends and I were reading Pynchon, Burroughs, Barth, Brautigan, Terry Southern, Ishmael Reed, Vonnegut, and others. Those books excited me, but they didn’t have the heavy impact the French writers had, because, with notable exceptions, avant-garde American fiction was very linear and reliant on standard narrative devices—playing with fiction’s conventions rather than trying to transcend them—whereas French writers like Genet and Céline and Bataille and Blanchot and so many others were working in a kind of visionary, poetic mode, and that approach appealed to me much more, probably in part because I was as enthralled by poetry as I was by fiction.

The next thing that really changed my world and thoroughly influenced my writing were the films of Robert Bresson. When I discovered them in the late seventies, I felt I had found the final ingredient I needed to write the fiction I wanted to write.

INTERVIEWER

What was the final ingredient?

COOPER

Recognizing that the films were entirely about emotion and, to me, profoundly moving while, at the same time, stylistically inexpressive and monotonic. On the surface, they were nothing but style, and the style was extremely rigorous to boot, but they seemed almost transparent and purely content driven. Bresson’s use of untrained nonactors influenced my concentration on characters who are amateurs or noncharacters or characters who are ill equipped to handle the job of manning a story line or holding the reader’s attention in a conventional way.

Altogether, I think Bresson’s films had the greatest influence on my work of any art I’ve ever encountered. In fact, the first fiction of mine that was ever published was a chapbook called Antoine Monnier, which was a god-awful, incompetent attempt to rewrite Bresson’s film Le diable probablement as a pornographic novella. So I came to writing novels through a channel that included experimental fiction, poetry, and nonliterary influences pretty much exclusively. I never read normal novels with any real interest or close attention.

INTERVIEWER

What are normal novels?

COOPER

Too much story, too much realism, too much overfamiliarity in general. They bought into the traditional, majority approach and opinion among American writers and arbiters of literature that life is most effectively depicted in fiction via one streamlined, time-proven method—the narrative arc, the sympathetic character, the snowballing plot, et cetera—and when I read work like that, all I saw were the writers’ slight variations on a central formula that seemed reductive and arbitrary and bogus.