Issue 198, Fall 2011

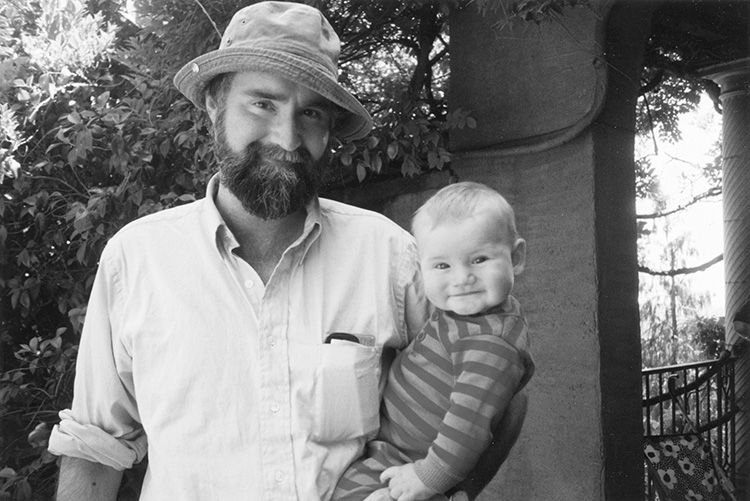

Nicholson Baker with his son, Elias, in Berkeley in 1994.

Nicholson Baker with his son, Elias, in Berkeley in 1994.

Nicholson Baker loves artificial constraints: the clarity they bring to a project, the odd angles and tones they inspire. The entirety of his first novel, The Mezzanine, takes place during a single escalator ride; his most recent work of nonfiction, Human Smoke, pieces together a history of World War II almost exclusively from snippets of contemporary accounts (newspapers, magazines, and diaries). So it was no surprise when Baker—sitting at his kitchen table, eating a tomato-and-cheese-and-cucumber sandwich—proposed a constraint for our interview. He asked—shyly, apologetically, but seriously—if we could somehow manage to conduct the entire thing without ever mentioning any of his books. Talking about them, he said, gives him a “cringe-y” feeling.

That constraint, fortunately, turned out to be impossible. To talk about Baker’s life is, inevitably, to talk about his work; the membrane separating the two is unusually thin. If Baker is not exactly one of his own protagonists, he is a close cousin, or a fraternal twin. He and they inhabit the same world—one of odd enthusiasms (Wikipedia, singing poems), microscopically observed mechanisms (pencil sharpeners, windshield wipers), onomatopoeic noises (clonk, kashoonk), and quotidian anthropology (few other authors would notice, as Baker did in The Mezzanine, that late-twentieth-century American men trying to pass through a door at the same time always say “oop” to each other instead of “oops”). Occasionally during our conversations, Baker would recall a specific memory from his childhood—say, the pleasure of listening to music through headphones in the dark—and end up describing, exactly, a scene he’d already described as the childhood memory of one of his characters.

Baker’s thirteen books divide roughly into three disparate categories: slim novels filled with idle thoughts about the trivia of daily life (The Mezzanine, Room Temperature, A Box of Matches); nonfictional polemics (Double Fold, Human Smoke); and wild sex fantasies (Vox, The Fermata, and, most recently, House of Holes). The books that don’t fit into those categories often manage to combine them. Checkpoint, a novel-in-dialogue about a man who wants to assassinate the president, is a wild polemical fantasy. In The Anthologist, a novel about a poet struggling to write the introduction to a poetry anthology, the trivia of daily life competes with a polemic for the hero’s attention and our own.

After some twenty-five years of writing, Baker’s reputation is as unusual as his work. He has been praised, widely and enthusiastically, for his style, humor, originality, and empathy. (As Martin Amis once put it, “Throughout his corpus there is barely an ordinary sentence or an ungenerous thought.”) At the same time, some critics have very publicly loathed a handful of his books, most vociferously Vox (“tedious”), The Fermata (“repellent”), Checkpoint(“scummy”), and Human Smoke (“childish”). Many of Baker’s talents are self-consciously small: meticulously inventive phrasemaking, a masterfully intimate tone, and a superhuman gift for observation. He has a Dutch-painterly reverence for everyday rituals and objects—a belief that they will start to glow with significance if we only pay close enough attention. This has left Baker open to the charge that the work itself is trivial, quaint—a bubble of old-fashioned belletrism floating through a harsh modern world. (Leon Wieseltier, writing in The New York Times, once called Baker’s novels “creepy hermeneutical toys.”)

What’s disguised by Baker’s cheerful tone, however, is his passionately sustained conviction that we should honor the details of our lives rather than getting carried away by projections and abstractions. In this quest, Baker has seemed continually willing to risk puzzling his fans and inflaming critics; he has shown an indifference to publishing fashions that few authors could have sustained. One index of this independence is that, although Baker has been published for his entire career in magazines such as The New Yorker and The Atlantic, he has never held a staff position. “I felt I had to be someone who would leap in from outside,” he told me, “and do some nutty thing and then run away cackling.”

Baker is fifty-four years old, but you can still see the teenager in him: he is self-consciously tall and shy, and his face turned red, often, when we talked about his books. He lives in a rambling eighteenth-century house on the border of Maine and New Hampshire. We spoke there for several hours, first in the kitchen and then in the living room, next to the fireplace in front of which he wrote A Box of Matches. Later, Baker drove me to a restaurant in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where, as we entered, a man exiting at the same time very distinctly said, “Oop!”

—Sam Anderson

INTERVIEWER

Let’s start with a very basic question. How do you write? With a pen? A pencil?

BAKER

I edit with a pen, I write on a computer. I’ve always had trouble with pencils because they get dull so quickly, or they just break, and then there’s that awful shuddery feeling when you’re trying to write with a couple of scraps of wood poking out.

INTERVIEWER

What about a mechanical pencil?

BAKER

Sure, but the leads in mechanical pencils have the problem of bending. They give and then they snap. And they don’t offer the pleasures of sharpening. That was always a big moment for me in grade school, to walk to the side of the classroom where the pencil sharpener was mounted on the wall and imagine the two-geared cylinders going around, gnashing away at the cone of wood. The pencil sharpener was probably the best thing about school back then, actually—a little chrome invention under your control. It had a thundering sound, a throat-clearing sound, that I especially liked—Ticonderoga is almost onomatopoetic. And of course I oversharpened and broke the point, so I got to stand there for a while making that sound, ticonderoga … oga … oga.

Then there was a while, when I was starting out as a writer, when I really needed to have a certain kind of pen. It was before the golden age of rollerball pens and gel pens and pens with rubber grips—there’s such a bewildering array now. It had a red barrel and I can’t remember the name of the manufacturer, which troubles me. It had an unusually smooth, fine-point roller.

INTERVIEWER

So you would use that.

BAKER

That’s what I wrote with. And then I decided that a real writer typed his drafts. My mother had a Sears typewriter. Starting in seventh grade, I tried typing once in a while on that. I memorized the keys by taping over them with black electrician’s tape. Later, when my father dropped me off at college, he bought me this postmodern-looking, low to the ground, Italian-designed, beautifully minimalist typewriter, a black Olivetti electric, that had a deep hum. I took it to Paris with me, and I wrote a couple pieces on it that ended up being published. Once I’d been published, I thought, Okay, let’s get serious now, you’re going to have to write on a manual typewriter. So I bought a hundred-twenty-five-dollar green Olivetti manual, which was very light, and I carried that around with me in a zippered case.

When I moved to Boston, in 1983, I typed at night on my green Olivetti manual, and during the day I made a living as a word-processing operator. Somewhere along the way—I think it was 1985—I got a Kaypro, one of the first portable computers. You clamped the keyboard to the front and these little simple clips went clonk. It had two floppy drives and looked like a small, portable piece of medical equipment. It was really a lovely machine. Every so often it would make a little grinding sound, like worn brake pads. I wrote my first novel on it, The Mezzanine. I love typing, actually—the sensation of typing on a keyboard or on an old-fashioned typewriter.

INTERVIEWER

How did The Mezzanine come about?

BAKER

My twenties weren’t terribly productive. I wasted a lot of time. I had a mental deadline that I would finish a book by the time I turned thirty. I blew the deadline. I had a job doing technical writing, which was really consuming me. I wasn’t sleeping. So my wife and I figured out that we could live for six months, mostly with the money she had saved up. I quit the job and wrote as hard as I’ve ever written. I would get up at eight in the morning and write until seven at night.

My wife was working two days a week, so I would take care of our daughter, Alice, on those days, and she took care of Alice on the other days. When you have a child, you get a surge of ambition, or a surge of hormonal urgency, to get something done, something worthy of your new station in life. I gave myself a new deadline: Finish the novel while you’re still thirty. Do something your child might be able to read when she grows up.

My code name for the book was “Desperation.”

INTERVIEWER

What was the writing process like?

BAKER

It was totally absorbing, the feeling of being sunk in the midst of a big, warm, almost unmanageable pond. I could sense all these notes I had, all these observations I’d saved up to use, finally arranging themselves in relation to one other. Somewhere in chapter three, I thought, my God, it’s a genuine chapter! And then later I got to chapter eight and a few things had happened—not much had happened, but something had happened.

I retyped the whole book. I was always a believer, even with word processing, that there’s something useful about having to retrace your steps from the beginning. And you have to print it out, too—you only get so far if you work by staring at a screen, because the resolution of the paper page is much higher. Your eye actually takes in things on paper more efficiently. I can fiddle around with something on a screen for days and think I’m getting somewhere, and it won’t be right. Then I’ll print it out and take it to bed, and instantly it’s obvious what’s bad about it, and I’ll cross out, cross out, cross out.

INTERVIEWER

It’s an unusual book—especially for a debut. Was it easy to find a publisher?

BAKER

Publishers didn’t really get it. It was rejected a lot of times, by nine or ten publishers. They all said they thought it wasn’t a novel. They didn’t get the footnotes—nobody was doing footnotes back then.

INTERVIEWER

That must have been heartbreaking.

BAKER

Not really. I knew it was a book that was a little bit different from what was going on at the time—I had De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater in mind as I wrote, because of the way it swirls around and revels in its digressions. A piece of my book had already appeared in The New Yorker. I figured that at some point someone would publish it. Once it came out in hardcover, a paperback editor at Vintage, Marty Asher, read it and liked it. He brought it out as a Vintage Contemporary, and that was tremendously exciting. I felt like I had been accepted into some strange club. Bright Lights, Big City was a Vintage Contemporary at that same time, and A Fan’s Notes and The Sportswriter.