You know that expression “famous last words”? We are naturally curious about people’s last words, but it would be interesting to compile an exhaustive list of the first words—not just sounds, actual words—spoken in a film, run them through a computer, and subject the results to some kind of processing and analysis. In this film the first words are spoken by the wife and they are: “Why did you take my watch?” Yes, the film’s hardly started, she’s only just woken up, and, from a husbandly point of view, she’s already nagging. Nagging him and calling him a thief. No wonder he wants out. But of course we’re also getting the big theme introduced: time. Tarkovsky is saying to the audience: Forget about previous ideas of time. Stop looking at your watches, this is not going to proceed at the speed of Speed, but if you give yourself over to Tarkovsky time, then the helter-skelter mayhem of The Bourne Ultimatum will seem more tedious than L’Avventura. “I think that what a person normally goes to the cinema for is time,” Tarkovsky has said, “whether for time wasted, time lost, or time that is yet to be gained.” This sentiment is only a couple of words away from being in perfect accord with something even the most moronic cinemagoer would agree with. Those words are a good, as in “What people go to the cinema for is a good time, not to sit there waiting for something to happen.” (Some people lie outside any kind of consensus of why we go to the cinema. They don’t go to the cinema at all. For Strike, a character in Richard Price’s novel Clockers, a movie, any movie, is just “ninety minutes of sitting there”—a remark that could be taken as a negative endorsement of Tarkovsky’s claim.)

She expands on this notion of time—she’s lost her best years, has grown old—while the man is brushing his teeth. As she does so, you’re reminded again of Antonioni, because the plain truth is she’s no Monica Vitti. Frankly, the combination of nagging and permanently faded looks seems like a compelling incentive to leave. She lays a whole guilt trip on him, but the usual terms—you only think of yourself—are reversed, given a kind of Dostoyevskian twist: Even if you don’t think of yourself ...[3]

She begs him to stay but, as she does so, you can see that she knows it’s in vain, that he’s going—even though he’s not actually said where he’s going. She says he’ll end up in prison. He says that everywhere’s a prison. Good answer. But a bad sign, marriagewise. It would seem that their relationship has got to the point where the default mode of communication is to bicker, quarrel, and contradict each other. It’s not a lot of fun, this mode, but it’s easy to get the hang of and immensely difficult to get out of once you’re in it: a prison, in fact. One assumes the man’s answer is intended metaphorically but the film often makes us wonder about when and where it is set and what its relationship is to the world beyond the screen. Stalker was made in the late 1970s, not the thirties or the fifties when the Soviet Union was a vast prison camp, when, in prison-camp slang (as Anne Applebaum points out in Gulag), “the world outside the barbed wire was not referred to as ‘freedom,’ but as the bolshaya zona, the ‘big prison zone,’ larger and less deadly than the ‘small zone’ of the camp, but no more human—and certainly no more humane.” By the time of Stalker, Communism had become, in Tony Judt’s words, “a way of life to be endured” (which sounds, incidentally, like an alternative translation of koyaanisqatsi, the Hopi Indian word meaning—as anyone who has ever enjoyed a couple of bong hits already knows—“way of life needing change” or “life out of balance”). Stalker is not a film about the Gulag, but the absent and unmentioned Gulag is constantly suggested, either by Stalker’s zek haircut or by the overlapping vocabulary.

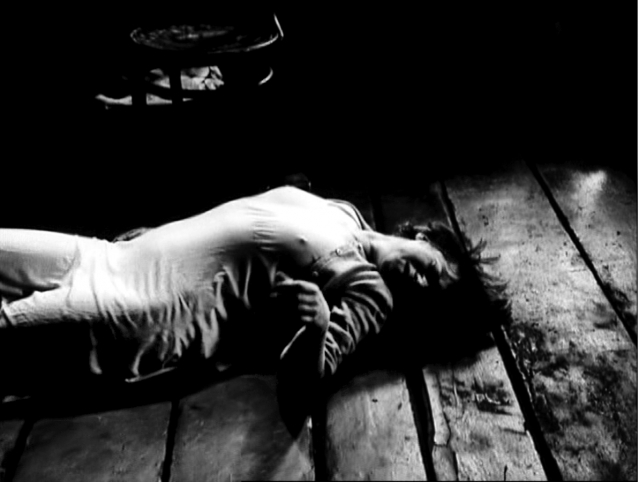

After Stalker leaves, his wife has one of those sexualized fits (nipples prominently erect), of which Tarkovsky seems to have been fond, writhing away on the hard floor in a climax of abandonment.[4]

He, on the other hand, like many men before and since, is on his way to the pub, making his way through railway sidings, beautifully desolate and puddly, in the postindustrial fog.

--

[3] Tarkovsky’s wife, Larissa, wanted this part and the director-husband was eager to give her the role. He was persuaded to drop her in favor of Alisa Freindlikh by other crew members, chief among them Georgy Rerberg, director of photography on Stalker—initially—and Tarkovsky’s previous film, Mirror. In making an enemy of Larissa, the seeds were perhaps sown for Rerberg’s later dismissal or departure—depending on whom you believe—from the film.

[4] Cf. The second resurrection of Hari, coming back to life, so to speak, in a see-through shorty nightie after drinking liquid oxygen in Solaris.