Issue 93, Fall 1984

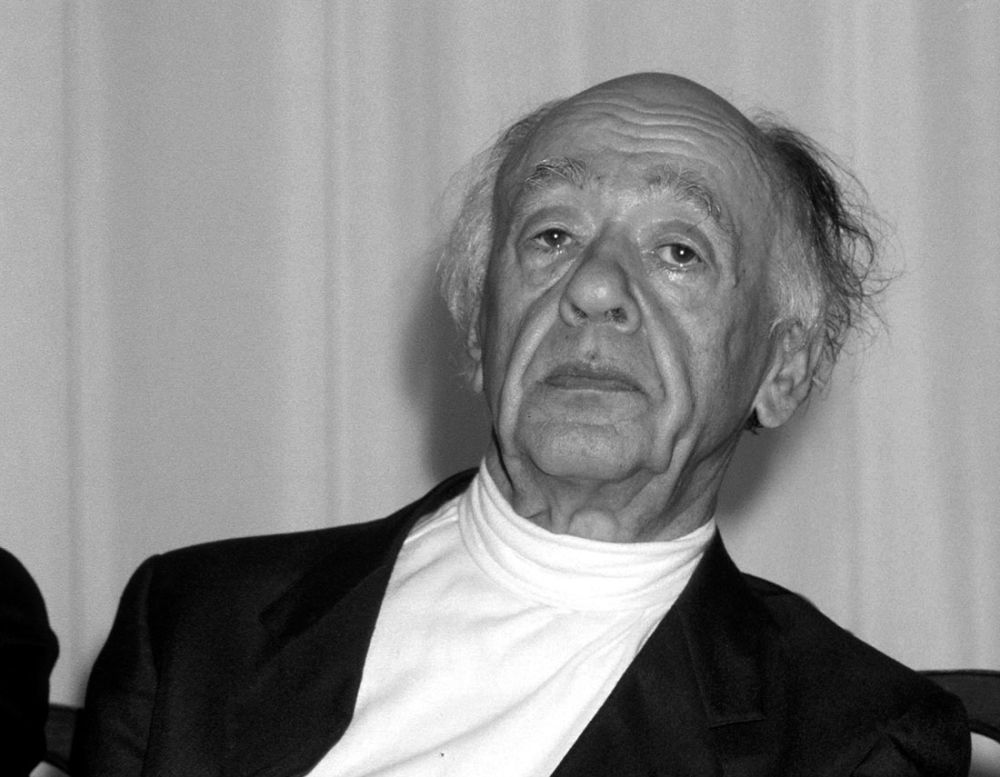

Eugene Ionesco, ca. 1985. Photograph by Eugene Ionesco

Eugene Ionesco, ca. 1985. Photograph by Eugene Ionesco

The last few years have been exceptionally busy for Eugène Ionesco. His seventieth birthday was celebrated in 1982 with a series of events, publications, and productions of his work, not only in France but worldwide. Hugoliades, Ionesco’s satirical portrait of Victor Hugo, which he wrote at the age of twenty, was newly published by Gallimard. In Lyons, Roger Planchon, the director of the Théâtre Nationale Populaire, staged Journey Among the Dead, a collage of Ionesco’s dreams, autobiographical writings, and extracts from his latest play, The Man with Suitcases. The show, which toured France to both critical and popular acclaim, was due to be staged at the Comédie Française in Paris. Recently, the cast of Ionesco’s two early plays The Bald Soprano and The Lesson gave a birthday party for the playwright which also celebrated both plays’ twenty-fifth year of uninterrupted runs at the Théâtre de la Huchette in Paris.

Over the past thirty years, Ionesco has been called a “tragic clown,” the “Shakespeare of the Absurd,” the “Enfant Terrible of the Avant-Garde,” and the “Inventor of the Metaphysical Farce”—epithets that point to his evolution from a young playwright at a tiny Left Bank theater to an esteemed member of the Académie Française. For the past forty-five years, Ionesco has been married to Rodika, his Romanian wife. They live in an exotic top-floor apartment on the Boulevard Montparnasse above La Coupole, surrounded by a collection of books and pictures by some of Ionesco’s oldest friends and colleagues, including Hemingway, Picasso, Sartre, and Henry Miller. Our interview took place in the drawing room, where Miró’s portraits, Max Ernst’s drawing of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros, and a selection of Romanian and Greek icons adorn the walls.

Ionesco, a small, bald man with sad, gentle eyes, seems quite fragile at first glance—an impression which is immediately belied by his mischievous sense of humor and his passionate speech. Beside him Rodika, also slight, with dark slanted eyes and an ivory complexion, looks like a placid oriental doll. During the course of the interview she brought us tea and frequently asked how we were getting on. The Ionescos’ steady exchange of endearments and their courtesy with one another reminded me of some of the wonderful old couples portrayed by Ionesco in many of his plays.

INTERVIEWER

You once wrote, “The story of my life is the story of a wandering.” Where and when did the wandering start?

EUGENE IONESCO

At the age of one. I was born near Bucharest, but my parents came to France a year later. We moved back to Romania when I was thirteen, and my world was shattered. I hated Bucharest, its society, and its mores—its anti-Semitism for example. I was not Jewish, but I pronounced my r’s as the French do and was often taken for a Jew, for which I was ruthlessly bullied. I worked hard to change my r’s and to sound Bourguignon! It was the time of the rise of Nazism and everyone was becoming pro-Nazi—writers, teachers, biologists, historians . . . Everyone read Chamberlain’s The Origins of the Twentieth Century and books by rightists like Charles Maurras and Léon Daudet. It was a plague! They despised France and England because they were yiddified and racially impure. On top of everything, my father remarried and his new wife’s family was very right-wing. I remember one day there was a military parade. A lieutenant was marching in front of the palace guards. I can still see him carrying the flag. I was standing beside a peasant with a big fur hat who was watching the parade, absolutely wide-eyed. Suddenly the lieutenant broke rank, rushed toward us, and slapped the peasant, saying, “Take off your hat when you see the flag!” I was horrified. My thoughts were not yet organized or coherent at that age, but I had feelings, a certain nascent humanism, and I found these things inadmissible. The worst thing of all, for an adolescent, was to be different from everyone else. Could I be right and the whole country wrong? Perhaps there were people like that in France—at the time of the Dreyfus trials, when Paul Déroulède, the chief of the anti-Dreyfussards, wrote “En Avant Soldat!”—but I had never known it. The France I knew was my childhood paradise. I had lost it, and I was inconsolable. So I planned to go back as soon as I could. But first, I had to get through school and university, and then get a grant.

INTERVIEWER

When did you become aware of your vocation as a writer?

IONESCO

I always had been. When I was nine, the teacher asked us to write a piece about our village fete. He read mine in class. I was encouraged and continued. I even wanted to write my memoirs at the age of ten. At twelve I wrote poetry, mostly about friendship—“Ode to Friendship.” Then my class wanted to make a film and one little boy suggested that I write the script. It was a story about some children who invite some other children to a party, and they end up throwing all the furniture and the parents out of the window. Then I wrote a patriotic play, Pro Patria. You see how I went for the grand titles!

INTERVIEWER

After these valiant childhood efforts you began to write in earnest. You wrote Hugoliades while you were still at university. What made you take on poor Hugo?

IONESCO

It was quite fashionable to poke fun at Hugo. You remember Gide’s “Victor Hugo is the greatest French poet, alas!” or Cocteau’s “Victor Hugo was a madman who thought he was Victor Hugo.” Anyway, I hated rhetoric and eloquence. I agreed with Verlaine, who said, “You have to get hold of eloquence and twist its neck off!” Nonetheless, it took some courage. Nowadays it is common to debunk great men, but it wasn’t then.

INTERVIEWER

French poetry is rhetorical, except for a few exceptions like Villon, Louise Labé, and Baudelaire.

IONESCO

Ronsard isn’t. Nor are Gérard de Nerval and Rimbaud. But even Baudelaire sinks into rhetoric: “Je suis belle, O Mortelle . . . ” and then when you see the actual statue he’s referring to, it’s a pompous one! Or: “Mon enfant, ma soeur, songe à la douceur, d’aller là-bas vivre ensemble . . . ” It could be used for a brochure on exotic cruises for American millionaires.

INTERVIEWER

Come on! There were no American millionaires in those days.

IONESCO

Ah, but there were! I agree with Albert Béguin, a famous critic in the thirties [author of Dreams and the Romantics], who said that Hugo, Lamartine, Musset, et cetera . . . were not romantics, and that French romantic poetry really started with Nerval and Rimbaud. You see, the former produced versified rhetoric; they talked about death, even monologued on death. But from Nerval on, death became visceral and poetic. They didn’t speak of death, they died of death. That’s the difference.

INTERVIEWER

Baudelaire died of death, did he not?

IONESCO

All right then, you can have your Baudelaire. In the theater, the same thing happened with us—Beckett, Adamov, and myself. We were not far from Sartre and Camus—the Sartre of La Nausée, the Camus of L’Etranger—but they were thinkers who demonstrated their ideas, whereas with us, especially Beckett, death becomes a living evidence, like Giacometti, whose sculptures are walking skeletons. Beckett shows death; his people are in dustbins or waiting for God. (Beckett will be cross with me for mentioning God, but never mind.) Similarly, in my play The New Tenant, there is no speech, or rather, the speeches are given to the Janitor. The Tenant just suffocates beneath proliferating furniture and objects—which is a symbol of death. There were no longer words being spoken, but images being visualized. We achieved it above all by the dislocation of language. Do you remember the monologue in Waiting for Godot and the dialogue in The Bald Soprano? Beckett destroys language with silence. I do it with too much language, with characters talking at random, and by inventing words.

INTERVIEWER

Apart from the central theme of death and the black humor which you share with the other two dramatists, there is an important oneiric, or dreamlike, element in your work. Does this suggest the influence of surrealism and psychoanalysis?

IONESCO

None of us would have written as we do without surrealism and dadaism. By liberating the language, those movements paved the way for us. But Beckett’s work, especially his prose, was influenced above all by Joyce and the Irish Circus people. Whereas my theater was born in Bucharest. We had a French teacher who read us a poem by Tristan Tzara one day which started, “Sur une ride du soleil,” to demonstrate how ridiculous it was and what rubbish modern French poets were writing. It had the opposite effect. I was bowled over and immediately went and bought the book. Then I read all the other surrealists—André Breton, Robert Desnos . . . I loved the black humor. I met Tzara at the very end of his life. He, who had refused to speak Romanian all his life, suddenly started talking to me in that language, reminiscing about his childhood, his youth, and his loves. But you see, the most implacable enemies of culture—Rimbaud, Lautréamont, dadaism, surrealism—end up being assimilated and absorbed by it. They all wanted to destroy culture, at least organized culture, and now they’re part of our heritage. It’s culture and not the bourgeoisie, as has been alleged, that is capable of absorbing everything for its own nourishment. As for the oneiric element, that is due partly to surrealism, but to a larger extent due to personal taste and to Romanian folklore—werewolves and magical practices. For example, when someone is dying, women surround him and chant, “Be careful! Don’t tarry on the way! Don’t be afraid of the wolf; it is not a real wolf!”—exactly as in Exit the King. They do that so the dead man won’t stay in infernal regions. The same thing can be found in the Tibetan Book of the Dead, which had a great impact on me too. However, my deepest anxieties were awakened, or reactivated, through Kafka.