Issue 93, Fall 1984

When Julio Cortázar died of cancer in February 1984 at the age of sixty-nine, the Madrid newspaper El Pais hailed him as one of Latin America’s greatest writers and over two days carried eleven full pages of tributes, reminiscences, and farewells.

Though Cortázar had lived in Paris since 1951, he visited his native Argentina regularly until he was officially exiled in the early 1970s by the Argentine junta, who had taken exception to several of his short stories. With the victory, last fall, of the democratically elected Alfonsín government, Cortázar was able to make one last visit to his home country. Alfonsín’s cultural minister chose to give him no official welcome, afraid that his political views were too far to the left, but the writer was nonetheless greeted as a returning hero. One night in Buenos Aires, coming out of a cinema after seeing the new film based on Osvaldo Soriano’s novel, No habra ni mas pena ni olvido, Cortázar and his friends ran into a student demonstration coming towards them, which instantly broke file on glimpsing the writer and crowded around him. The bookstores on the boulevards still being open, the students hurriedly bought up copies of Cortázar’s books so that he could sign them. A kiosk salesman, apologizing that he had no more of Cortázar’s books, held out a Carlos Fuentes novel for him to sign.

Cortázar was born in Brussels in 1914. When his family returned to Argentina after the war, he grew up in Banfield, not far from Buenos Aires. He took a degree as a schoolteacher and went to work in a town in the province of Buenos Aires until the early 1940s, writing for himself on the side. One of his first published stories, “House Taken Over,” which came to him in a dream, appeared in 1946 in a magazine edited by Jorge Luis Borges. It wasn’t until after Cortázar moved to Paris in 1951, however, that he began publishing in earnest. In Paris, he worked as a translator and interpreter for UNESCO and other organizations. Writers he translated included Poe, Defoe, and Marguerite Yourcenar. In 1963, his second novel Hopscotch—about an Argentine’s existential and metaphysical searches through the nightlife of Paris and Buenos Aires—really established Cortázar’s name.

Though he is known above all as a modern master of the short story, Cortázar’s four novels have demonstrated a ready innovation of form while, at the same time, exploring basic questions about man in society. These include The Winners (1960), 62: A Model Kit (1968), based in part on his experience as an interpreter, and A Manual for Manuel (1973), about the kidnapping of a Latin American diplomat. But it was Cortázar’s stories that most directly claimed his fascination with the fantastic. His most well-known story was the basis of Antonioni’s film by the same name, Blow-Up. Five collections of his stories have appeared in English to date, the most recent being We Love Glenda So Much. Just before he died, a travel journal was published, Los autonautas de la cosmopista, on which he collaborated with his wife, Carol Dunlop, during a voyage from Paris to Marseilles in a camping van. Published simultaneously in Spanish and French, Cortázar signed all author’s rights and royalties over to the Sandinista government in Nicaragua; the book has since become a best-seller. Two posthumous collections of his political articles on Nicaragua and on Argentina have also been published.

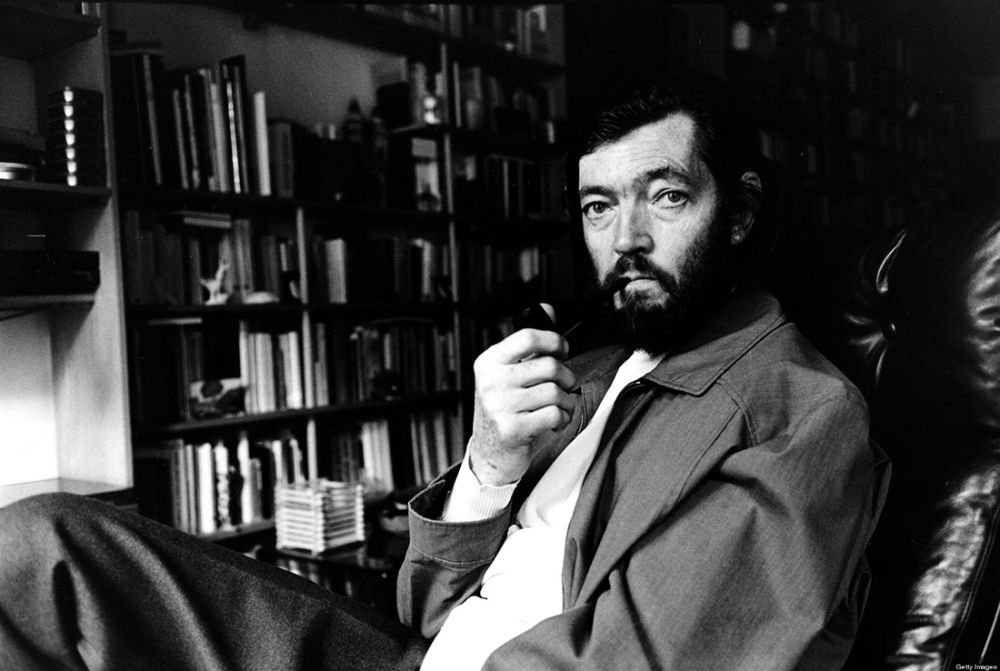

Throughout his expatriate years in Paris, Cortázar had lived in various neighborhoods. In the last decade, royalties from his books enabled him to buy his own apartment. The apartment, atop a building in a district of wholesalers and chinaware shops, might have been the setting for one of his stories: spacious, though crowded with books, its walls lined with paintings by friends.

Cortázar was a tall man, 6'4", though thinner than his photographs revealed. The last months before this interview had been particularly difficult for him, since his last wife, Carol, thirty years his junior, had recently died of cancer. In addition, his extensive travels, especially to Latin America, had obviously exhausted him. He had been home barely a week and was finally relaxing in his favorite chair, smoking a pipe as we talked.

INTERVIEWER

In some of the stories in your most recent book, Deshoras, the fantastic seems to encroach on the real world more than ever. Have you yourself felt as if the fantastic and the commonplace are becoming one?

JULIO CORTÁZAR

Yes, in these recent stories I have the feeling that there is less distance between what we call the fantastic and what we call the real. In my older stories, the distance was greater because the fantastic really was fantastic, and sometimes it touched on the supernatural. Of course, the fantastic takes on metamorphoses; it changes. The notion of the fantastic we had in the epoch of the gothic novels in England, for example, has absolutely nothing to do with our concept of it today. Now we laugh when we read Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto—the ghosts dressed in white, the skeletons that walk around making noises with their chains. These days, my notion of the fantastic is closer to what we call reality. Perhaps because reality approaches the fantastic more and more.

INTERVIEWER

Much more of your time in recent years has been spent in support of various liberation struggles in Latin America. Hasn’t that also helped bring the real and the fantastic closer for you, and made you more serious?

CORTÁZAR

Well, I don’t like the idea of “serious,” because I don’t think I am serious, at least not in the sense where one speaks of a serious man or a serious woman. But in these last few years, my efforts concerning certain Latin American regimes—Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, and now above all Nicaragua—have absorbed me to such a point that I have used the fantastic in certain stories to deal with this subject—in a way that’s very close to reality, in my opinion. So, I feel less free than before. That is, thirty years ago I was writing things that came into my head and I judged them only by aesthetic criteria. Now, though I continue to judge them by aesthetic criteria, first of all because I’m a writer—I’m now a writer who’s tormented, very preoccupied by the situation in Latin America; consequently that often slips into my writing, in a conscious or in an unconscious way. But despite the stories with very precise references to ideological and political questions, my stories, in essence, haven’t changed. They’re still stories of the fantastic.

The problem for an engagé writer, as they call them now, is to continue being a writer. If what he writes becomes simply literature with a political content, it can be very mediocre. That’s what has happened to a number of writers. So, the problem is one of balance. For me, what I do must always be literature, the highest I can do . . . to go beyond the possible. But, at the same time, to try to put in a mix of contemporary reality. And that’s a very difficult balance. In the story in Deshoras about the rats, “Satarsa”—which is an episode based on the struggle against the Argentine guerrillas—the temptation was to stick to the political level alone.

INTERVIEWER

What has been the response to such stories? Was there much difference in the response you got from literary people and that which you got from political ones?

CORTÁZAR

Of course. The bourgeois readers in Latin America who are indifferent to politics, or those who align themselves with the right wing, well, they don’t worry about the problems that worry me—the problems of exploitation, of oppression, and so on. Those people regret that my stories often take a political turn. Other readers, above all the young—who share my sentiments, my need to struggle, and who love literature—love these stories. The Cubans relish “Meeting.” “Apocalypse at Solentiname” is a story that Nicaraguans read and reread with great pleasure.

INTERVIEWER

What has determined your increased political involvement?

CORTÁZAR

The military in Latin America—they’re the ones who make me work harder. If they were removed, if there were a change, then I could rest a little and work on poems and stories that would be exclusively literary. But it’s they who give me work to do.

INTERVIEWER

You have said at various times that, for you, literature is like a game. In what ways?

CORTÁZAR

For me, literature is a form of play. But I’ve always added that there are two forms of play: football, for example, which is basically a game, and then games that are very profound and serious. When children play, though they’re amusing themselves, they take it very seriously. It’s important. It’s just as serious for them now as love will be ten years from now. I remember when I was little and my parents used to say, “Okay, you’ve played enough, come take a bath now.” I found that completely idiotic, because, for me, the bath was a silly matter. It had no importance whatsoever, while playing with my friends was something serious. Literature is like that—it’s a game, but it’s a game one can put one’s life into. One can do everything for that game.

INTERVIEWER

When did you become interested in the fantastic? Were you very young?

CORTÁZAR

It began in my childhood. Most of my young classmates had no sense of the fantastic. They took things as they were . . . this is a plant, that is an armchair. But for me, things were not that well defined. My mother, who’s still alive and is a very imaginative woman, encouraged me. Instead of saying, “No, no, you should be serious,” she was pleased that I was imaginative; when I turned towards the world of the fantastic, she helped by giving me books to read. I read Edgar Allan Poe for the first time when I was only nine. I stole the book to read because my mother didn’t want me to read it; she thought I was too young and she was right. The book scared me and I was ill for three months, because I believed in it . . . dur comme fer as the French say. For me, the fantastic was perfectly natural; I had no doubts at all. That’s the way things were. When I gave those kinds of books to my friends, they’d say, “But no, we prefer to read cowboy stories.” Cowboys were especially popular at the time. I didn’t understand that. I preferred the world of the supernatural, of the fantastic.