Issue 135, Summer 1995

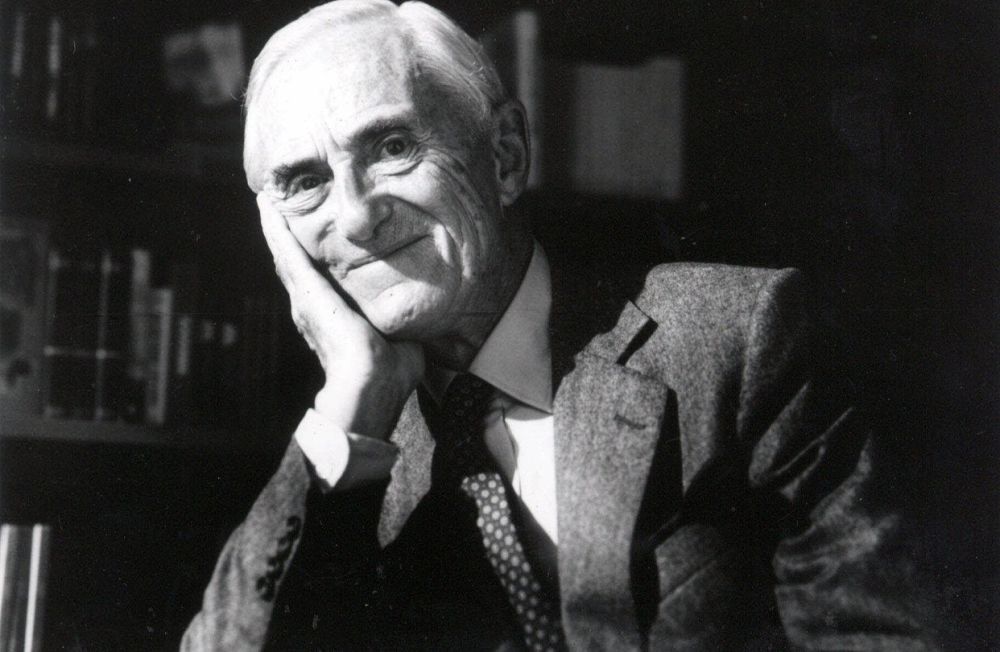

Patrick O'Brian. Photograph by Julio Nayan

Patrick O'Brian. Photograph by Julio Nayan

The serious American publication of Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin novels began in 1987. They were greeted with yelps and growls of satisfaction rising rapidly to a thunderous ovation as deserved as it was belated. But the earliest brilliant flicker of lightning dates back to 1952, when his first novel, Testimonies, appeared. Delmore Schwartz, in an omnibus review (which has lately become famous along with O’Brian) including novels by Hemingway, Steinbeck, Waugh, and Angus Wilson, gave O’Brian pride of place and praise.

Testimonies had been preceded by a collection of short stories, and was followed by novels, more stories, several poems, many translations from the French (including Papillon and most of Simone de Beauvoir’s books), more lately biographies of Joseph Banks and Picasso, a constant flow of book reviews, and of course the Aubrey-Maturin series, beginning with Master and Commander in 1969. Fifteen years earlier O’Brian had written The Golden Ocean, a cheerful fiction based on Anson’s expedition to the Pacific in 1740. (“I had been reading naval history for years and years, and I knew a fair amount about the sea: I wrote the tale in little more than a month, laughing most of the time.”) The novel is a lark, and had, as its author later noted, “pleasant consequences.” Among those are the now seventeen volumes of the Aubrey-Maturin series, which are in many languages, including Japanese, and are justly famed. O’Brian’s eloquent admirers include not merely distinguished critics and reviewers but noted novelists (Mary Renault wrote, “Master and Commander raised almost dangerously high expectations; Post Captain triumphantly surpasses them. Mr. O’Brian does not just have the chief qualifications of a first-class historical novelist, he has them all”), actors, judges, professors, reporters—and thousands upon thousands of fervent readers who thank the gods for him, quote him, thrust him confidently upon friends, and give whole sets for Christmas.

The young O’Brian spent long periods in England, “but it was Ireland and France that educated and formed me, in so far as I was educated and formed.” The reservation is too modest; he studied philosophy and the classics formally, and certainly has a way with languages. The young man met the sea, and canvas, with delight (“ . . . although I never became much of a topman, after a while I could hand, reef, and steer without disgrace, which allowed more ambitious sailoring later on”). During the war he and his wife drove ambulances and served in intelligence together. Afterward they lived briefly in Wales, but presently “sun and wine came to seem essential,” and they settled in a little fishing village in the Roussillon. O’Brian knew early that he was a writer, and seems never to have been tempted by other vocations. He is also a reader, of course, and the range of his knowledge is rather daunting, but the tact and skill with which he uses that knowledge are remarkable. He values privacy and dignity, loves his work and his home, resents interruptions but is unfailingly courteous. In our bizarre age of masquerade and mammon, of footlights and flashbulbs, of tabloids and television, O’Brian seems extraordinary: he is his own man, he does his work, he values history, the arts and sciences, morality. He lives on good terms with his neighbor and with Homer, with the birds in his garden and with Mozart, with his readers and with Linnaeus. He is surely “one of the best storytellers of the age,” as one eminent admirer put it, and his work accomplishes nobly the three grand purposes of art: to entertain, to edify, and to awe.

This interview took place by correspondence over a period of months in 1994.

INTERVIEWER

Delmore Schwartz wrote of Testimonies, “In O’Brian, as in Yeats, the most studied cultivation and knowledge bring into being literary works, which read as if they were prior to literature and conscious literary technique.” Homer and Hesiod come to mind. Are your “influences” all classical, or are there moderns as well among them?

PATRICK O’BRIAN

Before I comment on “influences” may I first take up Delmore Schwartz’s “conscious literary technique”? Since I grew up, I have never deliberately used any technique at all other than the physical shaping of my tale so that it more or less resembles what has been thought of as a novel for these last two hundred years. Earlier, in the wicious pride of my youth, I sometimes threw myself into postures, imitating writers I admired and producing a certain amount of Proust and water (the recipe for the Avignon lark pâté comes to mind: one lark, one horse) to Joyce and very small beer; but none of this survived the war, and by the time I was writing Testimonies, for example, I was setting down what I had to say in the words and with the rhythm that seemed right to what might perhaps be called my inner ear, and doing so without any immediate debt to anyone.

INTERVIEWER

Which does not mean that you were unaffected by literary predecessors. Just how do these influences operate? Can they teach you morality, or elegance, or plotting? Do you feel a special kinship to Smollett?

O’BRIAN

Of course deeper formative influences were there by the hundred, barely touching the conscious level: the obvious classics, together with a fair amount of Vulgate and later Latin, and people like Chaucer, the Elizabethans, Dryden, Pope, Johnson, Fielding, Jane Austen, as well as quantities of dear, somewhat out-of-the-way writers such as Camden, Selden, Burton, Isaac Disraeli, and by means of Waley, the Chinese poets. You mention Smollett. No, I feel little or no kinship with him. For although the influences that I have mentioned did not, as far as I know, teach me morality or elegance (can either be taught?) they did perhaps make me dislike a certain variety of coarseness that Smollett shares on occasion with Sterne, a kind of sniggering that calls for a complicity that I am unwilling to give, though I find Rabelais excellent company and laugh wholeheartedly with Chaucer when he is bawdy. “ ‘Te-hee!’ quod she, and clapt the window to” seems to me a splendid line.

INTERVIEWER

Along the same lines: your erudition, plotting, and style (to say nothing of Maturin’s quotations from a hundred classical authors, some indeed “out of the way”) seem not sudden ingenuities or laboriously prepared effects, but the products of habits of mind formed by long and serious reading. Which great literatures, which great writers, have taught you most? Do you reread them continually? Or is the past wholly incorporated, so to speak, so that rereading ceases to be a joy?

O’BRIAN

As for the point about prepared effects, they do not exist. Effects, in so far as there are any, either present themselves or they do not come at all. And if they do present themselves, it is because they rise from a fairly copious stirabout of reading in which countless books and pieces of books are merged, oddments coming to the surface either of their own volition or in response to some computer whose working is far beyond my reach.

Which great literature, which great writers have taught me most? An earnest and a solemn question, and it seems odiously flippant to say that all they have taught me is that writing (as Picasso said of painting) is not only but also. The eighteenth century had the notion that literature’s function was to encourage virtue and to lash vice; but that is scarcely a view shared by those who read for delight (or for pity and terror) rather than instruction, and although a man like Shakespeare may teach one respect, admiration, and humility to the point of putting down one’s pen, at least for a while, I do not believe he teaches anything else. Indeed, apart from the mechanical trades and the exact sciences, what of value can be taught? Taught directly? And where the heart of writing is concerned, if you have to ask, surely it ain’t no good.

Yet there are many who have certainly and directly taught me admiration, and yes, I do read them again and again. I have a Horace upstairs and a Horace down; last summer I read Homer right through in the warm evenings out of doors, with a female black redstart fluttering angrily about my head because I read under the light that was her usual perch; and indoors I have a set of Jane Austen, all early editions for the added delight of immediacy, that I very often consult and rarely put down in less than an hour. In all these and in the more glorious parts of Dickens, Boswell, Gibbon, and many more I continually find new joys. The same applies to very good painting: less so, alas, to top music other than plainchant.

INTERVIEWER

The Aubrey-Maturin series is shot through with the blissful sort of humor that cannot be invented or learned but must spring from deep within. Until The Golden Ocean, your work was not at all playful. Was it the sea that brought out your sunny side?

O’BRIAN

What you say about humor that “cannot be invented or learned but must spring from deep within” really applies to the rest of writing: le style c’est l’homme même, said Buffon, taking style in the broadest possible sense. But where the rest of your question is concerned fun came into my writing on the shores of the Mediterranean, with sea, wine, sun, and a happy marriage.

INTERVIEWER

Had you any formal training as a naturalist, biologist, taxonomist, or have you learned all that for the sheer joy of it? And medicine?

O’BRIAN

Science? What little I have was mostly acquired by osmosis: one relative was a bacteriologist, another a physicist who worked on radium with Rutherford and Louis de Broglie, another a geologist. Yet I was taught a certain amount of biology; and being very sick I necessarily learned a certain amount about medicine.

INTERVIEWER

Every now and then a Frenchly phrase pops up, e.g., “entered into the line of count.” Do you also read widely in French and hop from one language to the other all day?

O’BRIAN

Gallicisms: yes, they exist. My wife and I have spent most of our lives in France and we are both pretty well bilingual, my wife more purely than I, since as a little girl she went to school in French Switzerland. At one time we used them for fun, saying, for example, Foute it in the poubelle, and insensibly this has come to taint my English idiom. If I am suddenly asked my telephone number, I am sadly puzzled to say it in anything but French. Yet a slightly shaky idiom is a small price to pay for having the whole of French literature open to one; and French translations, too, for the great Russians, and how astonishingly good they are, are splendid in French, often ludicrous in English.

INTERVIEWER

The Russians: War and Peace is a “historical novel” (though Russia had not altered much in the interval), and many of its leading characters—even Platon—are aspects of Tolstoy or people he knew. Are Jack and Stephen aspects of you? Or do you think of them as friends? Or are they your creatures only?

O’BRIAN

I do not think they are. I am fond of them both, but I am in no way identified with either.