Issue 135, Summer 1995

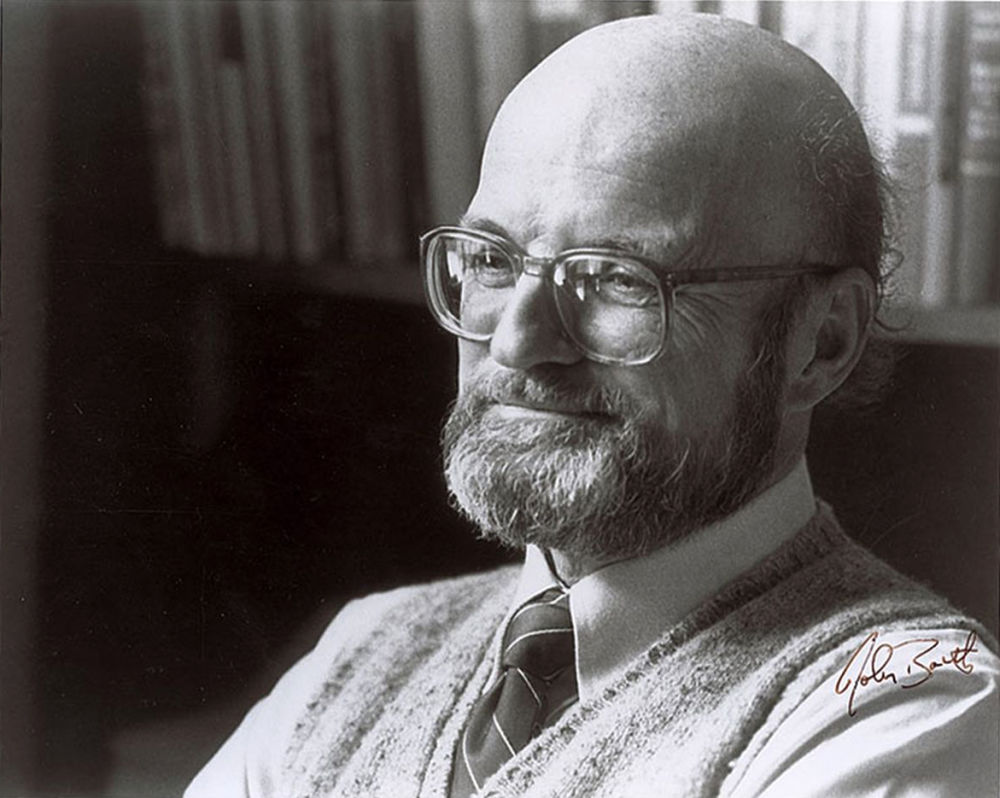

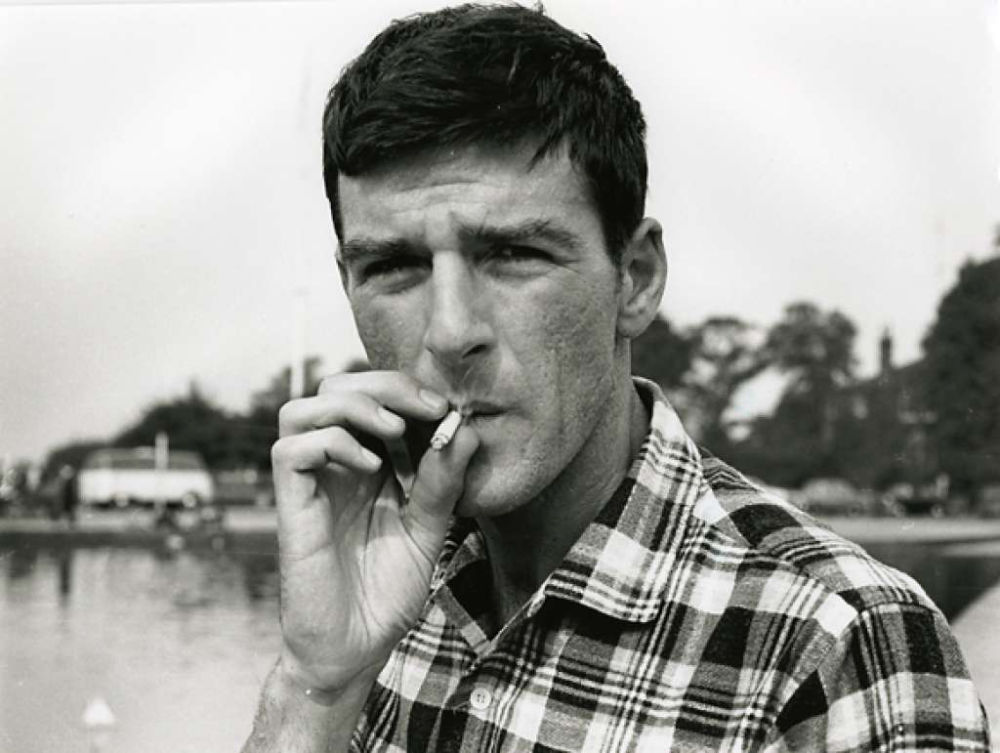

Thom Gunn 1960 Hampstead-White Stone Pond.

Thom Gunn 1960 Hampstead-White Stone Pond.

Thom Gunn was born in Gravesend, on the southern bank of the Thames estuary, in 1929. His childhood was spent mostly in that county, Kent, and in the affluent suburb of Hampstead in northwest London. A relatively happy boyhood was overshadowed first by his parents’ divorce when he was ten and then by his mother’s suicide when he was fifteen. In 1950, after two years’ national service in the army, he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study English. This was during the heyday of F. R. Leavis, whose lectures had a profound effect on Gunn’s early poetry.

It was in Cambridge that he discovered his homosexuality, falling in love with his lifelong partner, an American student named Mike Kitay. The wish to stay with Kitay led him to apply for American scholarships, and in 1954 he took up a creative writing fellowship at Stanford, where he studied with Yvor Winters. In 1960 he settled with Kitay in San Francisco and has lived there ever since, though longish spells have been passed in other places, notably London, where he lived on a travel grant from 1964 to 1965. For most of his time in California he has earned at least part of his income from the English Department at Berkeley, where he now teaches one semester a year.

His first book of poetry, Fighting Terms, written while he was at Cambridge, was published in 1954. Seven major collections have followed: The Sense of Movement (1957), My Sad Captains (1961), Touch (1967), Moly (1971), Jack Straw’s Castle (1976), The Passages of Joy(1982), and The Man with Night Sweats (1992). Other publications have included Positives(1967), a collection of verse captions to photographs by his brother Ander; editions of the work of Fulke Greville (1968) and Ben Jonson (1974); and a volume of critical and autobiographical prose, The Occasions of Poetry (1982). At the time of this interview he was assembling his Collected Poems (1994) and another volume of prose, Shelf Life (1993).

As a poet who lives in the United States yet is still thought of as an Englishman, Gunn is probably less widely read and discussed than his striking talent deserves. Nevertheless, he is much anthologized and has been the recipient of several literary prizes, the most recent being, in Britain, the first Forward Prize for Poetry (1992) and, in the U.S., a fellowship or “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation (1993).

There has always been a heroic edge to Thom Gunn’s poetry. That being the case, his appearance does not disappoint. He is tall and, for a man in his early sixties, remarkably lean and youthful. Tattooed arms and a single earring give him a faintly piratical air. In one of his poems he confesses to a liking for “loud music, bars, and boisterous men,” and a certain boisterous charm is one of his own most pleasing characteristics: as we talk, he laughs a great deal, very loudly, with rambunctious pleasure. He enjoys any hint of the vulgar or the tasteless, yet he is also a man of considerable refinement. Modest, considerate, and softly spoken, he was once described to me by one of his American friends as “the perfect English gentleman.”

Such complexities, even ambiguities, run deep. One of the most deeply erotic poets of our time, his style has often been praised for “chastity.” A celebrator of “the sense of movement,” he is strongly attached to his home and his routine. The occasion of this interview, for instance, is his first visit to his native country in thirteen years.

He was staying in his old university city of Cambridge and he visited my house every morning for three days. In all, we recorded three hours of conversation: we chatted with the tape on and stopped when we felt the talk beginning to flag. He was a relaxed interviewee, amusing and informative. He didn’t mind talking about personal matters, but he stopped well short of narcissism. What he said came across as spontaneous and yet one felt he was also well prepared. One was left with a sense of experience not easily translated into words.

INTERVIEWER

I wonder if we could begin with a brief description of how you live. I get the feeling, for instance, that you’re quite fond of routine.

THOM GUNN

Well, if you haven’t got a routine in your life by the age of sixty-two, you’re never going to get it. I spend half the year teaching and half the year on my own. I like the idea of scheduling my own life for half the year, but by the end of that time I’m really ready to teach again and have somebody else’s timetable imposed on me, because I’m chaotic enough that I just couldn’t be master of myself for the entire year. It would leave me too loose and unregulated. As I say, I’m eager to teach again in January and then, during the term, very often I’ll think of ideas for writing on but I usually don’t have time to work them out. By the time I can work them out at the end of the term, I’ve either lost them or else I’ve got them much more complex and intense, so that’s good too. I like the way my life has worked out very well. I live with some other men in a house in San Francisco. Somebody once said, Oh, you’ve got a gay commune. I said, No, it’s a queer household!—which I think was a satisfactory answer. Right now there’s only three of us there. There were five—one of them left and one of them died of AIDS. But we really fit in well together. We really do work as a family; we cook in turn, stuff like that. We do a lot of things together.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a writing routine?

GUNN

When anybody says, Do you have a routine, I always say piously it’s very important to have one, but in fact I don’t. I write poetry when I can and when I can’t, I write reviews, which I figure at least is keeping my hand in, doing some kind of writing. Finally, however difficult it is, it does make me happy in some weird way to do the writing. It’s hard labor but it does satisfy something in me very deeply. Sometimes when I haven’t written in some time, I really decide I’m going to work toward getting the requisite fever, and this would involve, oh, reading a few favorite poets intensively: Hardy, for example, John Donne, Herbert, Basil Bunting—any one of a number of my favorites. I try to get their tunes going in my head so I get a tune of my own. Then I write lots of notes on possible subjects for poetry. Sometimes that works, sometimes it doesn’t. It’s been my experience that sometimes about ten poems will all come in about two months; other times it will be that one poem will take ages and ages to write.

INTERVIEWER

Do you tend to work very hard on poems—revising and so on?

GUNN

It depends on the poem. Some poems come out almost right on the first draft—you really have to make very few small alterations. Others you have to pull to pieces and put together again. Those are two extremes—it might be anything between them. For instance, I have a poem called “Nasturtium.” I worked at it for ages and then decided it was just terrible. I only kept about one line, but then I rewrote the poem from a slightly different idea—I don’t remember the difference between the two, but it was a completely different poem from the first draft, and I think it only has about one or two lines in common with it. Only the last two lines, I think.

INTERVIEWER

When you start writing a poem, do you ever have a form in your head before you write, or do you always discover the form in writing?

GUNN

Again, sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t. For example, a poem called “Street Song.” Part of the idea of that poem was to write a modern version of an Elizabethan or Jacobean street song. So of course I knew it was going to rhyme, that it might have some kind of refrain—it was going to be a particular kind of poem. Other poems I don’t really know what they’re going to be like and I will jot down my notes for them kind of higgledy-piggledy all over the page, so that when I look at what I’ve got maybe the form will be suggested by what I have there. That’s mostly what happens with me. I don’t start by writing a couplet or something, knowing the whole thing’s going to be in couplets—though even that has happened.

INTERVIEWER

I know that you quite consciously and deliberately draw on other writers and writings in your poems. Could you describe that process a little? Do you quite ruthlessly plagiarize or pilfer?

GUNN

Yes, yes, yes. Well, T. S. Eliot gave us a pleasing example, didn’t he, quoting from people without acknowledgment? I remember a line in Ash Wednesday that was an adaptation of “Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope.” When I was twenty, I thought that was the most terrific line I’d read in Eliot! I didn’t know that it was a line from Shakespeare’s sonnets. I don’t resent that in Eliot and I hope people don’t resent it in me. I don’t make such extensive use of unacknowledged quotation as Eliot does, but every now and again I’ll make a little reference. This is the kind of thing that poets have always done. On the first page of The Prelude, Wordsworth slightly rewrites a line from the end of Paradise Lost: “The earth is all before me” instead of “The world was all before them.” He was aware that many an educated reader would recognize that as being both a theft and an adaptation. He was also aware, I’m sure, that a great many of his readers wouldn’t know it was and would just think it was original. That’s part of the process of reading—you read a poem for what you can get out of it.

INTERVIEWER

Actually, though, what you do much more often is model your poems on other poems.

GUNN

Well, I grew up when New Criticism was at its height and I took some of the things the New Critics said very literally. When I read, let’s say, George Herbert, I really do think of him as being a kind of contemporary of mine. I don’t think of him as being separated from me by an impossible four hundred years of history. I feel that in an essential way this is a man with a very different mind-cast from mine, but I don’t feel myself badly separated from him. I feel that we’re like totally different people with different interests writing in the same room. And I feel that way of all the poets I like.

INTERVIEWER

Donald Davie says of you in Under Briggflatts that you don’t use literary reference, as Eliot does, “to judge the tawdry present.” He finds that refreshing.

GUNN

I don’t regret the present. I don’t feel it’s cheap and tawdry compared with the past. I think the past was cheap and tawdry too. One of the things I noticed very early on—and I probably got it from an essay by Eliot—was that the beginning of Pope’s “Verses to the Memory of an Unfortunate Lady” is virtually taken from the beginning of the “Elegie on the Lady Jane Pawlet” by Ben Jonson. Now I don’t think most of Pope’s readers would have realized that. I don’t think Jonson was that much read in Pope’s time. I may be wrong . . . So I figured that was a very interesting thing to be able to do. But no, I don’t do it in the way Eliot and Pound do—to show up the present. I do it much more in the way I’ve described Wordsworth or Pope as doing it.