Issue 230, Fall 2019

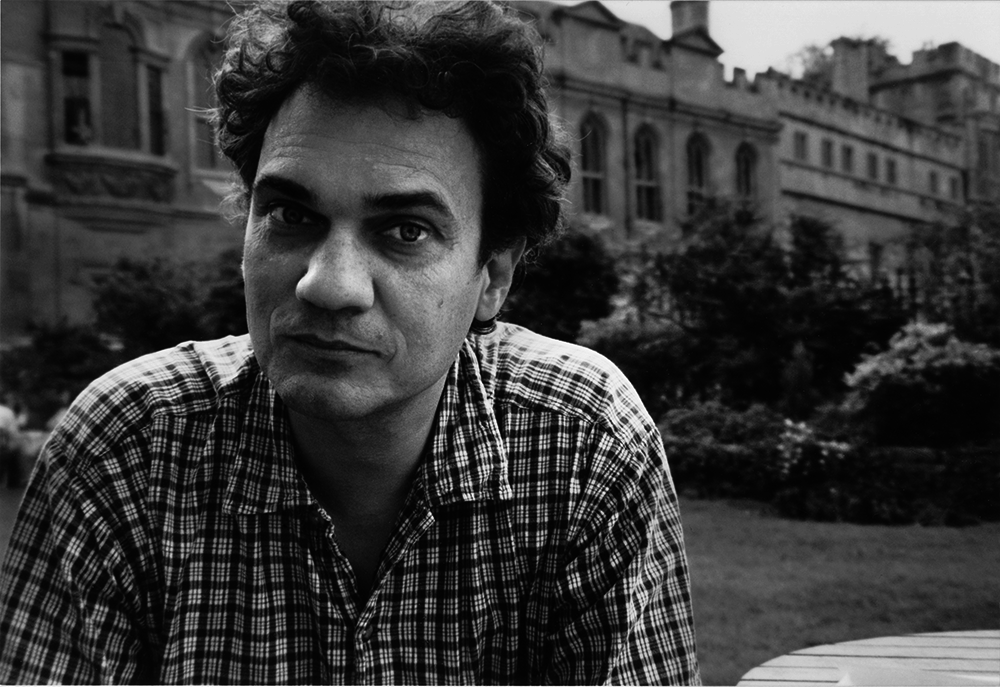

Photo courtesy of Barbara Hoffmeister

It’s a little strange to encounter Michael Hofmann in Gainesville. He has taught creative writing for over twenty years at the University of Florida, whose sprawling campus is dominated on its northern edge by a football stadium, the Swamp, where orange-and-blue Gators chomp their unlucky opponents. A short drive from there, you can pick your way past dozens of real gators, dusky green and preternaturally still, in the Paynes Prairie Preserve, which is also home to herds of wild horses and bison. How the bison got to Florida, and why they stayed, must be an interesting story. In one of Hofmann’s few Gainesville poems, “Freebird,” written after his first visit in 1990, he quotes D. H. Lawrence: “One forms not the faintest inward attachment, especially here in America.”

Hofmann’s native ground, in his translations as well as his poetry, is Europe: everywhere German is spoken, plus the seedier and derelict zones of Britain, where he arrived at the age of four and stayed for thirty years. Hofmann is the translator of over seventy books from the German—“a one-man Bibliothek,” in Adam Thirlwell’s words—ranging from the novels of Franz Kafka, Ernst Jünger, and Wolfgang Koeppen to the poetry of Gottfried Benn and Durs Grünbein. He is largely responsible for the rediscovery of the Austrian Jewish writer Joseph Roth, for a long time known to anglophone readers only for his historical novel Radetzky March. In one buoyant translation after another, Hofmann has brought out many other works—fables, novellas, realist fiction, sharp-eyed journalism—confirming Roth as one of the signal writers of the entre guerre period. Hofmann is also a prolific critic, whose reviews—stylish, unpredictable, occasionally ferocious, but just as often celebratory—have been collected in Behind the Lines (2002) and Where Have You Been? (2014).

Hofmann is the author of five books of poems, including Nights in the Iron Hotel (1983) and Acrimony (1986), which roam the wastelands of Thatcherism in a mood he calls “disconsolate punk.” The latter collection dissects his relationship with his father, the German writer Gert Hofmann, whose last three novels, The Film Explainer (1990, translation 1995), Luck (1992, 2002), and Lichtenberg and the Little Flower Girl (1994, 2004), Hofmann translated after Gert’s death in 1993. In 1990, the BBC made a documentary about Hofmann and his father, in which they travel from Bavaria across the newly opened border to Gert’s hometown of Limbach in the former East Germany. The father-son relationship, as depicted in the documentary, is full of silences and miscommunications; books and poems take the place of face-to-face exchanges. At one point we hear Hofmann reading a poem that evokes his father’s protagonists: “Maniacs, compulsive, virtuoso talkers, talkers for dear life, / talkers in soliloquies, notebooks, tape-recordings, last wills.”

Hofmann is not a virtuoso talker. His speech is soft and comes in short bursts, followed by intent silences. He rarely uses his hands, but his face is alive with an almost disconcerting variety of expressions, which an ideal transcription of our talk would have included. This interview took place over the course of two afternoons on the shady front porch of Hofmann’s small twenties brick house, a bike ride away from the university. Inside, papers and books, in German and in English, covered all the available surfaces. In the backyard were a grapefruit tree and a lemon tree, both heavy with fruit, in which Hofmann took obvious pleasure and a shy sort of pride.

INTERVIEWER

How did you discover Joseph Roth?

HOFMANN

The TLS assigned me a book of his in 1982, one of the first reviews I wrote. Weights and Measures. I liked it very much and said so. A bit later, I was asked to write an introduction to another one, Flight without End. Then John Hoare, his translator, died, and Chatto asked whether I’d do the next translation for them, which was The Legend of the Holy Drinker. They had heard that Ermanno Olmi was making a film of it, so they imagined there was a novel. Actually, it’s more like a parable. Twelve thousand words, something like that. When I delivered the translation, they went into a panic. How are we going to publish this?! They made me write a foreword. You couldn’t publish single novellas in English at that time. I felt I’d done something wicked.

INTERVIEWER

Did you feel right away that this was a writer you wanted to spend decades with?

HOFMANN

If I dared, yes. Even though everything seemed to have been done already, in the thirties, and then again in the seventies. But then we found more, and I redid some that had been done previously. I joke that I’ll end up redoing some of my own. Probably not a joke . . . I liked that he always seems to be in a hurry. Almost all the books are small—short and sweet and soon over. That’s agreeable for a translator. Even nicer is the speed at which things happen in the stories. A typical day’s work will include a marriage and a death and two murders. It keeps you interested. There’s so much glamour, so much drama, so much intensity, so much event. And a largely unfamiliar world. In the nineties, Eastern Europe was just coming out of the communist refrigerator where it had been since 1945. Suddenly, here you were reading about these towns and provinces that were once part of Austria-Hungary, which at the time seemed like an absurd construct. In the end I came around to thinking that what the world needs is Austria-Hungary. It was much better than our Common Market.