Helen Hennessy Vendler was born in Boston in 1933. She studied chemistry at Emmanuel College, a Roman Catholic school for women in Boston, and went to the University of Louvain after graduation on a Fulbright fellowship. She took her Ph.D. at Harvard in 1960 with a dissertation on Yeats, and the following year began teaching at Cornell. She later held regular appointments at Swarthmore, Haverford, Smith, and Boston University, as well as a Fulbright professorship at the University of Bordeaux. In 1981 she joined the faculty of Harvard. In 1990 she was given the title of Porter University Professor.

Vendler’s academic successes have been complemented by numerous appointments in non-university settings. She has been consultant poetry editor to The New York Times, president of the Modern Language Association, and since 1978, poetry critic for The New Yorker.

Vendler’s books include Yeats’s Vision and the Later Plays (1963), On Extended Wings: Wallace Stevens’s Longer Poems, which was awarded the James Russell Lowell Prize in 1969, The Poetry of George Herbert (1975), The Odes of John Keats (1983), Wallace Stevens: Words Chosen Out of Desire (1984), The Music of What Happens (1988), Soul Says (1995), The Given and the Made (1995), The Breaking of Style (1995) and Poems, Poets, Poetry(1995). She received the National Book Critics Circle Award for Criticism in 1981 for Part of Nature, Part of Us: Modern American Poets. She has edited two books: the Harvard Book of Contemporary American Poetry in 1985 and Voices and Visions: The Poet in America in 1987.

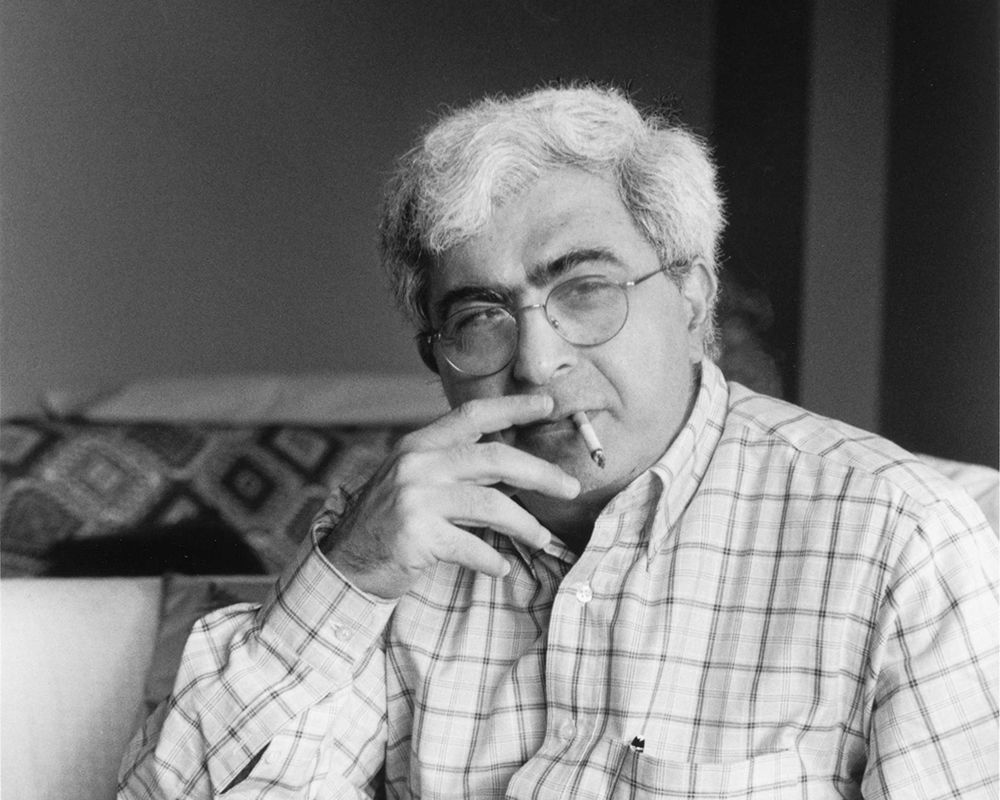

The following interview with Helen Vendler took place in the second-floor living room of her townhouse in Cambridge, a few blocks away from the Harvard English department. Mrs. Vendler wore a loose maroon sweater and black slacks. Around us were the mementos of a life devoted to poets and poetry. “Everything in this room was given to me,” she admitted. As we began our interview, Mrs. Vendler looked weary, but seemed to get a second wind as we continued. She’d awoken early that morning, worried about a meeting with her tax accountant. It was one of many appointments necessary before leaving for England, where she would be in residence at Magdalene College in Cambridge for the spring. After the interview we lingered on her stairwell, where many framed holographs and broadsides of poems—from A. R. Ammons, Frank Bidart, Seamus Heaney, Howard Nemerov, and Stephen Spender—were hung. There was also an occasional poem, a quatrain accompanying a stamped print of a peacock, received from James Merrill. And there was a poem, sent along with a dollsized gavel, from Elizabeth Bishop, when Mrs. Vendler was elected the second vice president of the Modern Language Association. An expression of anxiousness came over Mrs. Vendler’s face as we looked over this large wall of mementos, until she asked, like a concerned parent, if she had forgotten to mention anyone in her interview.

INTERVIEWER

Under the burden of manuscripts to read, letters of recommendation and endorsements of tenure to write, and student papers to grade, when do you find time to write?

HELEN VENDLER

I always write after I think for quite a long time, so the actual writing time is rather short. I think a lot of the work gets done when you have something on your mind while you’re doing many other things. Your unconscious mind is turning this over and over underneath, and then one morning you wake up with a whole lot of things formulated that you haven’t been consciously working on. At that point you can sit down and write. So, it’s not that it takes very long when I actually do it, but it takes quite a long time to work up to it.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think that your teaching has helped your criticism?

VENDLER

Oh, it would have to, if only because you learn more poems by heart every year from teaching them. They work on you then in a different way from the way they work on you when you’re reading them off the page. They live in you in different rhythms and come to mean more when you know them by heart.

INTERVIEWER

Do you write for a particular audience?

VENDLER

No, I write to explain things to myself.

INTERVIEWER

So your audience is yourself.

VENDLER

Well, I think of my audience in part as being the poet. What I would hope would be that if Keats read what I had written about the ode “To Autumn,” he would say, Yes, that is the way I wanted it to be thought of. And, Yes, you have unfolded what I had implied, or something like that. It would not strike the poet, I hope, that there was a discrepancy between my description of the work and the poet’s own conception of the work. I wouldn’t be very happy if a poet read what I had written and said, What a peculiar thing to say about this work of mine.

INTERVIEWER

No poet has ever done that?

VENDLER

No, not yet. I should add that they may have been too polite to say that.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think your criticism is hard to read?

VENDLER

I think that a lot of things are hard to read if you’re not in the vocabulary flow of that particular discourse. I sometimes forget that even though the words I’m using are fairly ordinary words, the concepts around which they cluster, which are the long concepts of literary tradition, may not be familiar to an audience. People who write about science for the general public also have to think a little about making certain concepts clear that would be second nature to anyone in their labs.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think of yourself as the heir to a particular critic? You worked on your Ph.D. with I. A. Richards, didn’t you?

VENDLER

No, I audited two classes of his when I was in graduate school at Harvard. The chairman would not permit me to take Richards’s class because Richards was based in the School of Education, not in the Department of English (Richards came to Harvard on a Carnegie Grant developing Basic English). His course was scratched off my program card by the chairman, and Chaucer was sternly substituted for it. Nothing daunted, I simply audited a course and a seminar from Richards. He certainly was the most important influence on me, except for John Kelleher. They were the two most indelible teachers that I had at Harvard—I. A. Richards because he gave full weight to every word in a poem and might track the history of a word back to Plato, taking it back through various philosophical and literary associations until the whole historical and cultural richness of the word was exposed. And John Kelleher, because he saw the human situation from which a given poem would arise; since he was an historian, he noted the political situation, or the social situation. In each case, in his class in Irish poetry, the poem was seen to spring out of the trial, struggle, relation of events in the history of Ireland. So in those two ways—both contextualizing ways, historically contextualizing in the case of Kelleher, and philosophically and literarily contextualizing in the case of Richards—they influenced me. They were both magnificent readers of poetry aloud.