Issue 205, Summer 2013

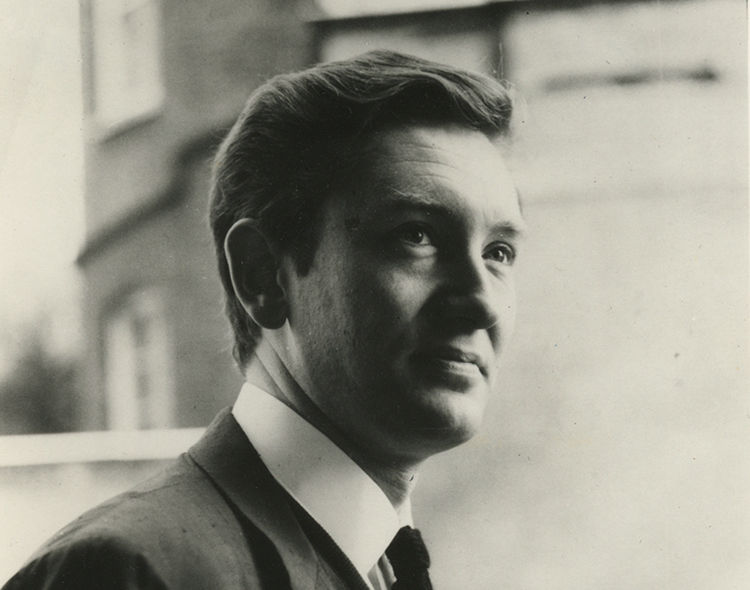

Holroyd, ca. 1965.

Holroyd, ca. 1965.

In an e-mail giving directions to his house, Michael Holroyd joked, “To help you I have arranged to have the front door painted red.” In fact, I knew I had reached the right house when I looked through the narrow window beside that vivid front door and saw a stack of books by Holroyd and by his wife, Margaret Drabble.

Michael de Courcy Fraser Holroyd was born in 1935 to an Anglo-Irish father and Swedish mother. He lived, after their divorce, with his paternal grandparents and an unmarried aunt in Maidenhead, outside London. In his memoir Basil Street Blues, which he has called a “prequel” to his biographies, he describes his solitary childhood and the atmosphere of eccentricity, acrimony, instability, and disappointment in which he grew up. He attended Eton College, was briefly and unhappily articled as a clerk in a law firm, and did his National Service. He and Drabble married in 1982.

Holroyd published his first book, a life of the novelist and biographer Hugh Kingsmill, in 1964, but it was his two-volume biography of Lytton Strachey (1967–68) that launched his career. In its frank and sympathetic treatment of Strachey’s love life, it also advanced the genre—much as Strachey’s compression and irreverent irony in Eminent Victorians had sixty years earlier. The book also benefited, as Holroyd has noted, from good timing: male homosexuality was decriminalized in England and Wales in 1967. And it was one of the first major studies of the Bloomsbury circle—indeed it helped to refocus interest on Strachey, Virginia Woolf, and their friends.

Two volumes on Augustus John followed, in 1974 and 1975, then the fifteen-year project that was his four-volume study of Bernard Shaw. His group portrait of the actors Henry Irving and Ellen Terry and their families, A Strange Eventful History, appeared in 2008. Holroyd has also published three autobiographical works, which he sees as a kind of trilogy—Basil Street Blues, Mosaic, and A Book of Secrets—and which are also meditations on biographical research and writing. There have been one-volume versions of each of his three major biographies; various edited books; and two collections of essays. He continues to write for the book section of the Guardian. Among many other honors, Holroyd was made a CBE in 1989 and was knighted in 2007 for “services to English literature.” In 2005 he received the David Cohen Prize for Literature, the first (and still only) time it has been given to a biographer.

Another e-mail before our first meeting suggested that we might “talk about you and not me.” Holroyd was witty and skilled at deflecting questions, but he was also generous and open. Our conversations took place over two extended afternoons in the summer of 2012.

—Lisa Cohen

INTERVIEWER

How do you choose your subjects?

HOLROYD

My very first subject, Hugh Kingsmill, was an accidental subject. I came across his writings and his books in a public library, which in a sense was my university. One reason he appealed to me is that he believed life was divided not between men and women, Tory and Labour, or one nationality and another, but between people of will and of imagination, all of whom sought a sort of unity. People of will often did so by force. Those of imagination detected a harmony underlying the discord of our lives. And that latter idea was very pleasant to me, because it appealed to my laziness. It meant I didn’t have to go out and fight, and, after having done National Service in the army, this was an attractive alternative. So I wrote about Kingsmill. I particularly liked his little book on the writer and editor Frank Harris, which seemed to me a wonderful mixture of irony and lyricism. And a minor subject in that book was Lytton Strachey, because Kingsmill was considered a follower of Strachey, who evolved into my next subject. That happened again with Augustus John, who appeared in Strachey, and then with Shaw, who appeared in Augustus John. And so it has gone on. It gives me the illusion of them choosing me, rather than me choosing them.

INTERVIEWER

What does it mean to you to be a biographer?

HOLROYD

I’ve always believed that there’s no such thing as a definitive biography and, particularly if you write about writers, that you are offering your subject the opportunity to write one more book, posthumously, of course, and in collaboration with you. Even if you and I were writing about the same subject, and even if our research were identical, we would produce different books. The dates and so on would be the same, but some themes would seem important to you and insignificant to me.

INTERVIEWER

You have written that you have “traded somewhat in invisibility as a biographer.”

HOLROYD

I believe that we are there between the lines, but most readers are not particularly aware of us.

INTERVIEWER

Are there subjects you considered but didn’t pursue?

HOLROYD

I thought a long time ago that Katherine Mansfield was a good subject. And I was asked to do one or two other books—Pamela Hansford Johnson, Stephen Spender—but I was always in the middle of something else. I was also asked to do a life of Jacqueline du Pré, whom I met, but I wasn’t competent to do it.

INTERVIEWER

Because you felt you didn’t know enough about music?

HOLROYD

Yes. It would have been interesting—in a way my subjects have been the tutors I never had, because I didn’t go to university. So I would have learned a lot. But it was difficult, too, because she was alive, and she suggested how I should do it, and I thought, This won’t work. I think it’s important to keep a distance from the person you’re trying to get close to.

INTERVIEWER

How do you negotiate that paradox?

HOLROYD

I don’t plot it. I do it instinctively, I enter the life. I do a lot of research and I believe in the magical as well as the meaningful—in seeing the actual documents, in one’s hand actually touching the paper. I can’t prove that it does something, but I hope that it gives one an extra sense of intimacy.

But I’m not the barrister for that person. Indeed, it’s not a courtroom case at all. Writing a biography has to do with trying to let the person live again, in a different time, for the reader. In a way, I don’t know what I do. It may also be connected to a wish to see what one has in common with someone who is completely different and of another time, but not completely out of reach. The person lives, in a sense, and you are involved with somebody you never knew. You haven’t had that life, but you know about it and are in it. That’s wonderful, to me.

INTERVIEWER

It strikes me that your earlier books were about men, whereas your focus has turned lately to women.

HOLROYD

In fact, quite often women have been my subjects. Even if the book has a single man on the title page, women have taken over the narrative for a long time. Carrington took over half of Lytton Strachey, and in translations they call it Carrington and not Strachey. And of course Christopher Hampton’s film based on it was called Carrington.