Issue 195, Winter 2010

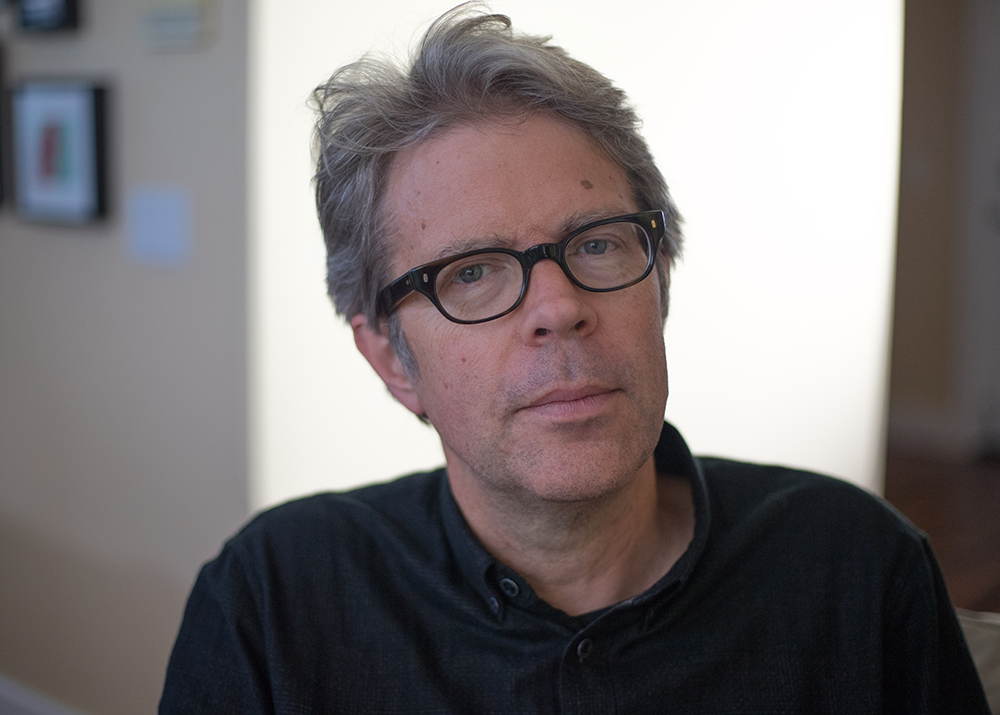

Photo by Shelby Graham, courtesy of Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Jonathan Franzen’s fiction bears the mark of a Midwest upbringing, his books preoccupied with quiet lives nurtured there and broken apart by contact with the rest of the world. But four long novels into an unusually public career, Franzen now moves about the country quite a bit, living most of the year in New York, where he writes in an office overlooking busy 125th Street, and some of it in a leafy community on the outskirts of Santa Cruz, where I met him just a few days before his most recent novel, Freedom, was released.

The scale of Freedom’s rapturous reception isn’t yet evident on the morning of our first conversation, though the book has already been called “the novel of the century,” and its author has just become the first writer in a decade to appear on the cover of Time magazine; a visit to the White House is soon to come. At the same time, two popular female novelists have been arguing, via Twitter, that Franzen owes his stature to the prejudices and gender asymmetries of book reviewing, and there are hints, too, that a broader backlash is brewing. (In London a few weeks later, he’ll have his glasses stolen by pranksters at a book party.) As we drive through the morning fog, Franzen recounts both sides to me as if he has no vested interest in either position—his stance is that of a detached, and slightly amused, observer.

Jonathan Franzen was born in 1959, in Western Springs, Illinois, and raised in Webster Groves, a suburb of St. Louis. The youngest of three children, Franzen grew up in a home dominated by pragmatic parents—his father an engineer, his mother a homemaker—who saw little value in the arts and who encouraged him to occupy himself instead with more practical subjects. A fascination with the sciences hangs over much of Franzen’s early writing, composed before his arrival at Swarthmore College. One unpublished story describes a visit from Pythagoras. An early play about Isaac Newton was championed by a physics teacher at Webster Groves High School.

Franzen describes his first book, The Twenty-Seventh City (1988), as a sci-fi novel that is all fi and no sci—a concept-driven omnibus fiction in which a group of influential and politically ambitious Indians, led by the former police commissioner of Bombay, infiltrate the bureaucracy of an unspectacular Midwestern town and terrorize its residents. The Twenty-Seventh City is set in his native St. Louis, but Franzen wrote the majority of the novel while employed as a research assistant at Harvard University’s Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, where he worked crunching data on seismic activity. This experience would enrich his second novel, Strong Motion (1992), an intimate depiction of a Massachusetts family whose emotional and economic lives are disrupted by a series of unexpected earthquakes in the Boston area.

Strong Motion signaled the start of a turbulent decade for Franzen, as he suffered personal losses—the death of his father; divorce from Valerie Cornell, his wife of fourteen years—and struggled to come to terms with the purpose of writing fiction after his first two novels won critical praise but dishearteningly few readers. Those struggles were the subject of much of the searching nonfiction he wrote during the nineties, and his midcareer masterpiece The Corrections (2001) was the outcome. The expansive saga of a disjointed Midwestern family, The Corrections won the National Book Award and the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, and introduced Franzen, then a relatively obscure author of ambitious fiction, to the broad audience of readers he had long been seeking—a broader audience than any literary novelist of his generation.

The following interview took place over two days in an office borrowed from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Situated amid redwoods on the mountain rim above Santa Cruz and Monterey Bay, the office would have offered an ocean view, but a makeshift arrangement of towels, bedsheets, and pillows had been engineered to block out the combined dangers of light and distraction. Improvised window treatments aside, Franzen prefers his work space to resemble Renée Seitchek’s house in Strong Motion—a “bare, clean place.” Aside from a laptop, the only personal items in the room were six books, arranged in a single pile: a study of William Faulkner, Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, and four works by John Steinbeck.

INTERVIEWER

Have you matured as a writer?

FRANZEN

When The Twenty-Seventh City was being misunderstood, and when Strong Motion was failing to find an audience, I assumed that the problem was not the writer but the wicked world. By the time I was working on Freedom, though, I could see that some of the contemporaneous criticisms of those books had probably been valid—that the first really was overdefended and inexplicably angry, and that the politics and thriller plotting (and, again, the inexplicable anger) of the second really were sometimes obtrusive. The writer’s life is a life of revisions, and I came to think that what needed revision were my own earlier books.

One of the great problems for the novelist who persists is the shortage of material. We all solve the problem in different ways; some people do voluminous research on nineteenth-century Peru. The literature I’m interested in and want to produce is about taking the cover off our superficial lives and delving into the hot stuff underneath. After The Corrections I found myself thinking, What is my hot material? My Midwestern childhood, my parents, their marriage, my own marriage—I’d already written two books about this stuff, but I’d been younger and scared and less skilled when I wrote them. So one of the many programs in Freedom was to revisit the old material and do a better job.

INTERVIEWER

Better how?

FRANZEN

I understand better how much of writing a novel is about self-examination, self-transformation. I spend vastly more time nowadays trying to figure out what’s stopping me from doing the work, trying to figure out how I can become the person who can do the work, investigating the shame and fear: the shame of self-exposure, the fear of ridicule or condemnation, the fear of causing pain or harm. That kind of self-analysis was entirely absent with The Twenty-Seventh City, and almost entirely absent with Strong Motion. It became necessary for the first time with The Corrections. And it became the central project with Freedom—so much so that the actual writing of pages was almost like a treat I was given after doing the real work.

INTERVIEWER

There was a nine-year interlude between those two novels.

FRANZEN

The Corrections cast a shadow. The methods I’d developed for it—the hypervivid characters, the interlocking-novellas structure, the leitmotifs and extended metaphors—I felt I’d exploited as far as they could be exploited. But that didn’t stop me from trying to write a Corrections-like book for several years and imagining that simply changing the structure or writing in the first person could spare me the work of becoming a different kind of writer. You always reach for the easy solution before you, in defeat, submit to the more difficult solution.

There certainly was no shortage of content by the middle of the last decade. The country was in the toilet, we’d become an international embarrassment, and those materialistic master languages that I’d mocked in The Corrections were becoming only more masterful. And I still had my own deep autobiographical material, which I’d employed in well-masked form in the first two novels. Eventually I realized that the only way forward was to go backward and engage again with certain very much unresolved moments in my earlier life. And that’s what the project then became: to invent characters enough unlike me to bear the weight of my material without collapsing into characters too much like me.

INTERVIEWER

Your first publication was a collaborative play called The Fig Connection, which you wrote in high school. What interested you about drama?

FRANZEN

I’m that oddity of a writer who had a good high-school experience, and I did a lot of acting in various plays. Theater for me was mainly a way of having fun in groups, as opposed to pairing off into couples who necked all night in a back seat. It was a kind of prolonged innocence. I wasn’t particularly in love with the theater, and the plays that my friends and I wrote weren’t literary. We were just making stuff up for fun. Until I was twenty-one, I had no concept of literature, really.

INTERVIEWER

Had your childhood been innocent, too?

FRANZEN

I always seemed to be the last person to find out about things that everybody else knew. I was literally still playing with building blocks, albeit artistically and with friends, during my senior year in high school.

INTERVIEWER

Was your writing encouraged at home?

FRANZEN

Mostly not, no. I hate the word creative, but it’s not a bad description of my personality type, and there was no place for that in my parents’ house. They considered art of all kinds, including creative writing, frivolous. Art was something I could do in my free time, and if I could get school credit for it, so much the better. But it was actively discouraged as a serious pursuit. My parents were dismayed and perplexed and angry when my older brother Tom stopped studying architecture and majored in film, and when he went to the Art Institute in Chicago and got an M.F.A. Tom was the only working artist I knew, and I idolized him and wanted to be like him, rather than like my parents. But I’d seen the grief he’d gotten from them, so I kept my own plans secret for as long as possible.

My dad, although he didn’t get a good formal education, was tremendously smart and curious. He read to me every night throughout my early childhood, always my dad, not my mom. Having grown up bathed nightly in his strong opinions, I became a fairly opinionated person myself and was happy to be able to keep him company. He read Time magazine cover to cover every week, and we talked about whatever was going on in the world. So, strangely, there was a lot of intellectual discussion in that otherwise unintellectual house. But there were no literary books on my parents’ shelves. I had no category for what I wanted to do, and this was the great excitement of writing The Fig Connection, seeing how well it worked as a student drama, and then, wonder of wonders, getting it published. This was the moment when a world of possibility opened up: I remember thinking, I’m actually good at writing—and isn’t this fun?