Issue 175, Fall/Winter 2005

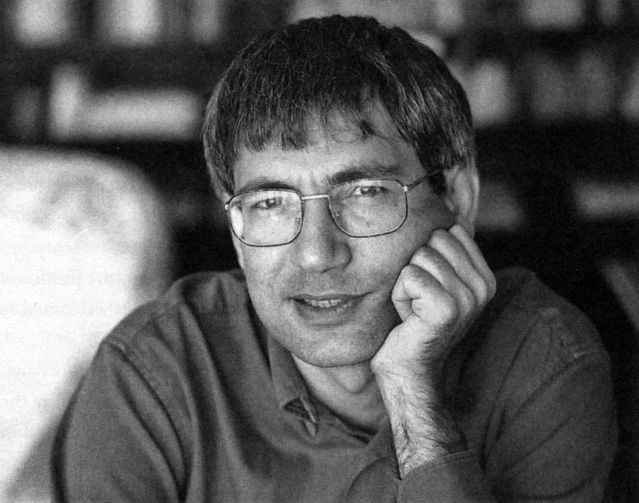

Pamuk in 1996. Photograph by Matthias Zeininger Berlin.

Pamuk in 1996. Photograph by Matthias Zeininger Berlin.

Orhan Pamuk was born in 1952 in Istanbul, where he continues to live. His family had made a fortune in railroad construction during the early days of the Turkish Republic and Pamuk attended Robert College, where the children of the city’s privileged elite received a secular, Western-style education. Early in life he developed a passion for the visual arts, but after enrolling in college to study architecture he decided he wanted to write. He is now Turkey’s most widely read author.

His first novel, Cevdet Bey and His Sons, was published in 1982 and was followed by The Silent House (1983), The White Castle (1985/1991 in English translation), The Black Book(1990/1994), and The New Life (1994/1997). In 2003 Pamuk received the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award for My Name Is Red (1998/2001), a murder mystery set in sixteenth-century Istanbul and narrated by multiple voices. The novel explores themes central to his fiction: the intricacies of identity in a country that straddles East and West, sibling rivalry, the existence of doubles, the value of beauty and originality, and the anxiety of cultural influence. Snow (2002/2004), which focuses on religious and political radicalism, was the first of his novels to confront political extremism in contemporary Turkey and it confirmed his standing abroad even as it divided opinion at home. Pamuk’s most recent book is Istanbul: Memories and the City (2003/2005), a double portrait of himself—in childhood and youth—and of the place he comes from.

This interview with Orhan Pamuk was conducted in two sustained sessions in London and by correspondence. The first conversation occurred in May of 2004 at the time of the British publication of Snow. A special room had been booked for the meeting—a fluorescent-lit, noisily air-conditioned corporate space in the hotel basement. Pamuk arrived, wearing a black corduroy jacket over a light-blue shirt and dark slacks, and observed, “We could die here and nobody would ever find us.” We retreated to a plush, quiet corner of the hotel lobby where we spoke for three hours, pausing only for coffee and a chicken sandwich.

In April of 2005 Pamuk returned to London for the publication of Istanbul and we settled into the same corner of the hotel lobby to speak for two hours. At first he seemed quite strained, and with reason. Two months earlier, in an interview with the Swiss newspaper Der Tages-Anzeiger, he had said of Turkey, “thirty thousand Kurds and a million Armenians were killed in these lands and nobody but me dares to talk about it.” This remark set off a relentless campaign against Pamuk in the Turkish nationalist press. After all, the Turkish government persists in denying the 1915 genocidal slaughter of Armenians in Turkey and has imposed laws severely restricting discussion of the ongoing Kurdish conflict. Pamuk declined to discuss the controversy for the public record in the hope that it would soon fade. In August, however, Pamuk’s remarks in the Swiss paper resulted in his being charged under Article 301/1 of the Turkish Penal Code with “public denigration” of Turkish identity—a crime punishable by up to three years in prison. Despite outraged international press coverage of his case, as well as vigorous protest to the Turkish government by members of the European Parliament and by International PEN, when this magazine went to press in mid-November Pamuk was still slated to stand trial on December 16, 2005.

INTERVIEWER

How do you feel about giving interviews?

ORHAN PAMUK

I sometimes feel nervous because I give stupid answers to certain pointless questions. It happens in Turkish as much as in English. I speak bad Turkish and utter stupid sentences. I have been attacked in Turkey more for my interviews than for my books. Political polemicists and columnists do not read novels there.

INTERVIEWER

You’ve generally received a positive response to your books in Europe and the United States. What is your critical reception in Turkey?

PAMUK

The good years are over now. When I was publishing my first books, the previous generation of authors was fading away, so I was welcomed because I was a new author.

INTERVIEWER

When you say the previous generation, whom do you have in mind?

PAMUK

The authors who felt a social responsibility, authors who felt that literature serves morality and politics. They were flat realists, not experimental. Like authors in so many poor countries, they wasted their talent on trying to serve their nation. I did not want to be like them, because even in my youth I had enjoyed Faulkner, Virginia Woolf, Proust—I had never aspired to the social-realist model of Steinbeck and Gorky. The literature produced in the sixties and seventies was becoming outmoded, so I was welcomed as an author of the new generation.

After the mid-nineties, when my books began to sell in amounts that no one in Turkey had ever dreamed of, my honeymoon years with the Turkish press and intellectuals were over. From then on, critical reception was mostly a reaction to the publicity and sales, rather than the content of my books. Now, unfortunately, I am notorious for my political comments—most of which are picked up from international interviews and shamelessly manipulated by some Turkish nationalist journalists to make me look more radical and politically foolish than I really am.

INTERVIEWER

So there is a hostile reaction to your popularity?

PAMUK

My strong opinion is that it’s a sort of punishment for my sales figures and political comments. But I don’t want to continue saying this, because I sound defensive. I may be misrepresenting the whole picture.

INTERVIEWER

Where do you write?

PAMUK

I have always thought that the place where you sleep or the place you share with your partner should be separate from the place where you write. The domestic rituals and details somehow kill the imagination. They kill the demon in me. The domestic, tame daily routine makes the longing for the other world, which the imagination needs to operate, fade away. So for years I always had an office or a little place outside the house to work in. I always had different flats.

But once I spent half a semester in the U.S. while my ex-wife was taking her Ph.D. at Columbia University. We were living in an apartment for married students and didn’t have any space, so I had to sleep and write in the same place. Reminders of family life were all around. This upset me. In the mornings I used to say goodbye to my wife like someone going to work. I’d leave the house, walk around a few blocks, and come back like a person arriving at the office.

Ten years ago I found a flat overlooking the Bosphorus with a view of the old city. It has, perhaps, one of the best views of Istanbul. It is a twenty-five-minute walk from where I live. It is full of books and my desk looks out onto the view. Every day I spend, on average, some ten hours there.

INTERVIEWER

Ten hours a day?

PAMUK

Yes, I’m a hard worker. I enjoy it. People say I’m ambitious, and maybe there’s truth in that too. But I’m in love with what I do. I enjoy sitting at my desk like a child playing with his toys. It’s work, essentially, but it’s fun and games also.

INTERVIEWER

Orhan, your namesake and the narrator of Snow, describes himself as a clerk who sits down at the same time every day. Do you have the same discipline for writing?

PAMUK

I was underlining the clerical nature of the novelist as opposed to that of the poet, who has an immensely prestigious tradition in Turkey. To be a poet is a popular and respected thing. Most of the Ottoman sultans and statesmen were poets. But not in the way we understand poets now. For hundreds of years it was a way of establishing yourself as an intellectual. Most of these people used to collect their poems in manuscripts called divans. In fact, Ottoman court poetry is called divan poetry. Half of the Ottoman statesmen produced divans. It was a sophisticated and educated way of writing things, with many rules and rituals. Very conventional and very repetitive. After Western ideas came to Turkey, this legacy was combined with the romantic and modern idea of the poet as a person who burns for truth. It added extra weight to the prestige of the poet. On the other hand, a novelist is essentially a person who covers distance through his patience, slowly, like an ant. A novelist impresses us not by his demonic and romantic vision, but by his patience.