Issue 80, Summer 1981

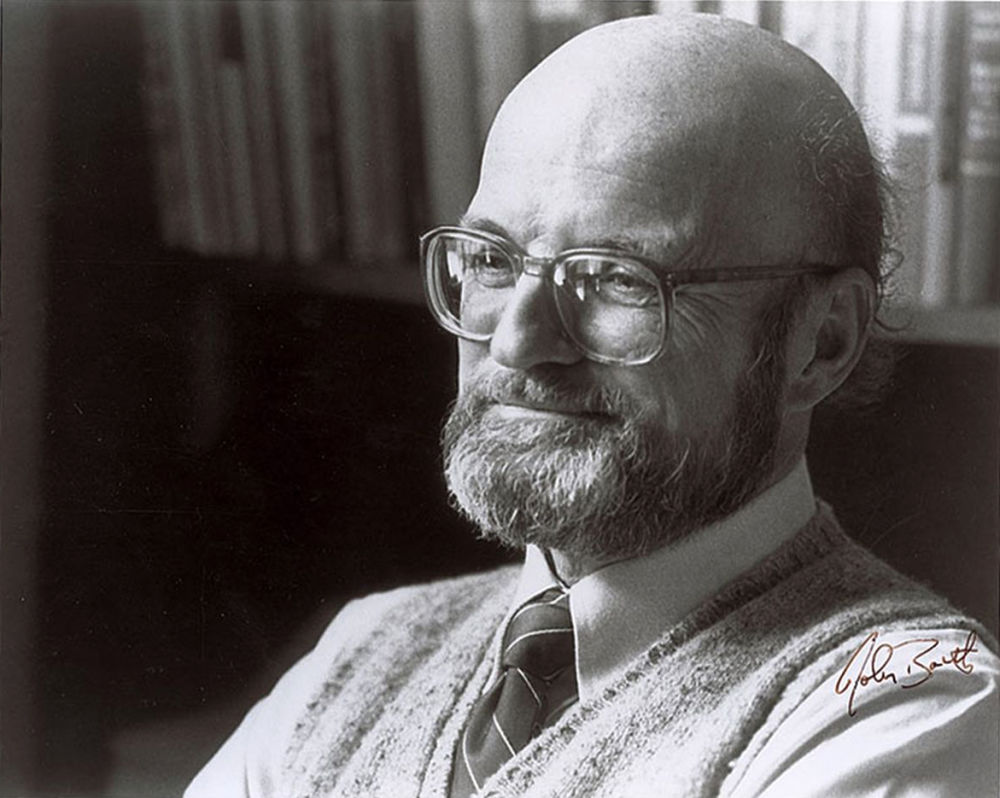

Donald Barthelme, Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Library

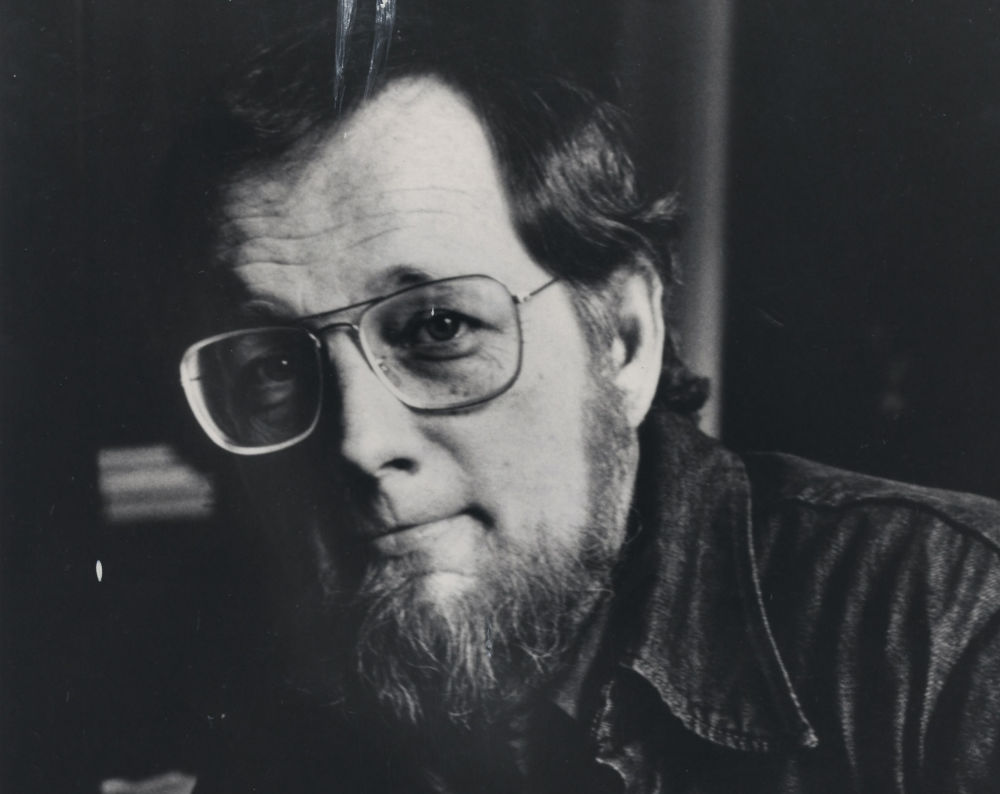

Donald Barthelme, Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Houston Library

Asked for his biography, Donald Barthelme said, “I don’t think it would sustain a person’s attention for a moment.” He was born, in Philadelphia, deep in the deep Depression (1931) and raised from it in Houston, Texas. There he endured a normal childhood, attended the University of Houston, studied philosophy under Maurice Natanson, and worked on a local newspaper. Then he was drafted, served in Korea, and returned to Houston, which he later left for New York City. There he did editorial work, especially for Location, and his odd short fictions made themselves known. Soon he became the most startling of the staid New Yorker’s regular contributors, and he still is.

He lives in New York City—“I move around quite happily. Alertly, but happily”—in a second-floor apartment in the West Village, cannily located between St. Vincent’s Hospital and a self-confessedly famous pizza parlor. The typical Barthelme interview is terse if not abrupt, but to this one he devoted large chunks of a weekend. He began at a dinner with fellow writer Ann Beattie and others, continued for two days in his spacious living room, and ended symmetrically at an elegant dinner prepared by his wife, Marion.

The talk was continuous and preferably about someone other than himself. He praised many favorite writers, including Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Kleist, Kafka, Hemingway, S. J. Perelman, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, and Beckett. (“Beckett, I suppose, made it possible for me to write. . . .”) He spoke enthusiastically of philosophers and psychologists, and of many contemporary writers. He refused the role of esoteric writer addressing a coterie audience. (“I assume that they’re kind of worn-down people like you and me . . . plain walking-around citizens.”) And like all sensible artists he fudged the conceptualization of his story writing. (“All the magic comes from the unconscious. If there is any magic.”)

The transcribed interview, with traffic noises, the clinking of glasses, and Marion Barthelme’s cheery voice still echoing in the background, was sent dutifully to the author. Many moons later and after much brooding and revision, the following dialogue emerged, cleansed of mere actuality and posing its figures in no landscape. The Platonic idea of an interview. But one may still intuit the old knobkerrie meditatively rubbed on the sleeve of the rumpled tweed jacket, the smoky setter asleep before the faithful fire . . . and now the writer’s ascetic features, framed in a square Danish Calvinist’s beard, soften benignly as the interviewer ventures his first academic question:

INTERVIEWER

You’re often linked with Barth, Pynchon, Vonnegut, and others of that ilk. Does this seem to you inhuman bondage or is there reason in it?

BARTHELME

They’re all people I admire. I wouldn’t say we were alike as parking tickets. Some years ago the Times was fond of dividing writers into teams; there was an implication that the Times wanted to see gladiatorial combat, or at least a soccer game. I was always pleased with the team I was assigned to.

INTERVIEWER

Who are the people with whom you have close personal links?

BARTHELME

Well, Grace Paley, who lives across the street, and Kirk and Faith Sale, who live in this building—we have a little block association. Roger Angell, who’s my editor at the New Yorker, Harrison Starr, who’s a film producer, and my family. In the last few years several close friends have died.

INTERVIEWER

How do you feel about literary biography? Do you think your own biography would clarify the stories and novels?

BARTHELME

Not a great deal. There’s not a strong autobiographical strain in my fiction. A few bits of fact here and there. The passage in the story “See the Moon?” where the narrator compares the advent of a new baby to somebody giving him a battleship to wash and care for was written the night before my daughter was born, a biographical fact that illuminates not very much. My grandmother and grandfather make an appearance in a piece I did not long ago. He was a lumber dealer in Galveston and also had a ranch on the Guadalupe River not too far from San Antonio, a wonderful place to ride and hunt, talk to the catfish and try to make the windmill run backward. There are a few minnows from the Guadalupe in that story, which mostly accompanies the title character through a rather depressing New York day. But when it appeared I immediately began getting calls from friends, some of whom I hadn’t heard from in some time and all of whom were offering Tylenol and bandages. The assumption was that identification of the author with the character was not only permissible but invited. This astonished me. One uses one’s depressions as one uses everything else, but what I was doing was writing a story. Merrily merrily merrily merrily.

Overall, very little autobiography, I think.

INTERVIEWER

Was your childhood shaped in any particular way?

BARTHELME

I think it was colored to some extent by the fact that my father was an architect of a particular kind—we were enveloped in modernism. The house we lived in, which he’d designed, was modern and the furniture was modern and the pictures were modern and the books were modern. He gave me, when I was fourteen or fifteen, a copy of Marcel Raymond’s From Baudelaire to Surrealism, I think he’d come across it in the Wittenborn catalogue. The introduction is by Harold Rosenberg, whom I met and worked with sixteen or seventeen years later, when we did the magazine Location here in New York.

My mother studied English and drama at the University of Pennsylvania, where my father studied architecture. She was a great influence in all sorts of ways, a wicked wit.

INTERVIEWER

Music is one of the few areas of human activity that escapes distortion in your writing. An odd comparison: music is for you what animals were for Céline.

BARTHELME

There were a lot of classical records in the house. Outside, what the radio yielded when I was growing up was mostly Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys; I heard him so much that I failed to appreciate him, failed to appreciate country music in general. Now I’m very fond of it. I was interested in jazz and we used to go to black clubs to hear people like Erskine Hawkins who were touring—us poor little pale little white boys were offered a generous sufferance, tucked away in a small space behind the bandstand with an enormous black cop posted at the door. In other places you could hear people like the pianist Peck Kelley, a truly legendary figure, or Lionel Hampton or once in a great while Louis Armstrong or Woody Herman. I was sort of drenched in all this. After a time a sort of crazed scholarship overtakes you and you can recite band rosters for 1935 as others can list baseball teams for the same year.

INTERVIEWER

What did you learn from this, if anything?

BARTHELME

Maybe something about making a statement, about placing emphases within a statement or introducing variations. You’d hear some of these guys take a tired old tune like “Who’s Sorry Now?” and do the most incredible things with it, make it beautiful, literally make it new. The interest and the drama were in the formal manipulation of the rather slight material. And they were heroic figures, you know, very romantic. Hokie Mokie in “The King of Jazz” comes out of all that.