Issue 164, Winter 2002-2003

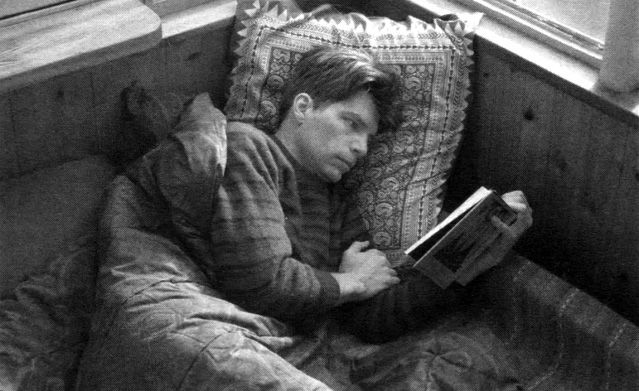

Until Richard Powers traveled to bookstores across the United States in 1998 to promote his sixth novel, Gain, he was as mysterious, having always spurned interviews, as he was revered. His cult of readers consumed, analyzed, and puzzled over his stereoscopic novels—steeped in art, genetics, medicine, artificial intelligence—but the curious who turned out to see the private author in bookstores were greeted not by a grave intellectual hooded with worry, but a tall, boyish man, as gentle and ingratiating as an old friend.

Powers was born on June 18, 1957 in Evanston, Illinois, the fourth of five children. His father was a junior-high-school principal, his mother a homemaker. He was raised on the north side of Chicago until he was eleven, when his family moved to Bangkok, where his father ran an international school for five years.

At the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Powers studied physics, rhetoric, and literature as an undergraduate, and earned a master’s degree in English in 1979. Having consumed the great modernists—Joyce, Mann, Kafka, and Musil—he decided, in his spare time, to teach himself computer programming.

Powers moved to Boston to work as a programmer, but soon quit to write his first novel. A venturesome reflection on photography, memory, and war, Three Farmers on Their Way to a Dance was published in 1985 and nominated for a National Book Critics Circle Award. With a garland of glowing reviews for his debut, Powers returned to Urbana, where he began his second novel, Prisoner’s Dilemma (1988), “my memorial to a sick father.” The book alternates between a bittersweet depiction of a Midwestern family coming apart at the seams and a funny, poignant portrayal of America during World War II, including a fantasy sequence of Walt Disney making a propaganda movie in a Japanese-American internment camp.

While writing Prisoner’s Dilemma, Powers moved to southern Holland. There, he wrote The Gold Bug Variations, supported by a MacArthur “genius” grant. Inspired by Edgar Allen Poe’s short story, “The Gold Bug,” and Bach’s Goldberg Variations, the novel braids the lives of a research librarian (based in part on Powers’s sister), a wayward painter, and a maverick geneticist into a six-hundred-and-forty-page meditation on the infinite mutation of genes, music, and love. It too was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award.

Powers moved back to Urbana in 1992 and finished his dire novel about history’s lost children, Operation Wandering Soul, published the following year and nominated for a National Book Award. Set in a pediatric ward in “Angel City,” Powers modeled the perpetually exhausted protagonist, Dr. Kraft, on his older brother, who was a surgeon at Martin Luther King Hospital in the Watts district of Los Angeles in the eighties.

In 1995, Powers experienced nearly unanimous critical acclaim with Galatea 2.2, another National Book Critics Circle nominee. He pushed the boundaries of metafiction by calling his main character “Richard Powers,” a reclusive novelist who holes up in the Center for the Study of Advanced Sciences in a midwestern university called “U.,” where he falls under the cynical tutelage of a neuroscientist who insists he can teach a supercomputer to pass the master’s oral exam in literature. The zeitgeistian look at artificial intelligence, fused with the author’s very real vulnerability and pain over a broken love affair, earned him his widest readership to date.

As a writer-in-residence at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Powers taught creative-writing classes and wrote Gain. The novel movingly details a midwestern single mother dying of ovarian cancer as it chronicles the one-hundred-and-seventy-year history of the fictitious Clare and Chemical Company. Based in part on his own experiences in cancer wards caring for terminally ill friends, Powers’s portrayal of his protagonist’s chemotherapy treatments rings as true as his insights: “We must be mad; that’s the only possible explanation. Thinking we could housebreak life, beat the kinks out of it, teach it to behave. Complete, collective, species-wide insanity.”

A year later, Powers released Plowing the Dark, another dual narrative. The first follows a one-time latest-rage New York painter, recruited by a Seattle computer company to create a virtual-reality installation. The other story takes place in a prison cell in Beirut, where an English teacher is imprisoned by a radical Muslim sect for an offhand joke about spying made to his class. “The first rule of any classroom,” he reminds himself the first day in prison. “Never resort to irony.” The narrative threads weave into a single portrait when the painter learns that the computer code with which she has created her virtual-reality installation is the same language guiding the smart bombs in the Gulf War. Praising the novel, the critic John Leonard wrote, “Everybody else just talks about alienation, estrangement, and the unbearable lightness of being.” Powers “actually does something about them.”

What Powers does in The Time of Our Singing, published in January 2003, is to delve into nothing less than America’s dark history of racism. He explores it through the twentieth-century experiences of the Strom family. Born of a father who is a white Jewish physicist and a mother who is a black singer, the three Strom children—Jonah, Joey, and Ruth—chase dreams of transcendence through classical music and radical politics until their paths cross in the novel’s extraordinary denouement. The novel once again demonstrates Power’s incredible range as a writer, of which he himself is rightly proud. “One of my pleasures as an artist is to reinvent myself with each new book,” he says. “If you’re going to immerse yourself in a project for three years, why not stake out a chunk of the world that is completely alien to you and go traveling?”

The following interview is the product of several meetings and conversations. The first came in the spring of 1998, when he was working on Plowing the Dark and living in a garage apartment near Stony Brook, Long Island. The conversation took place in a café; Powers arrived on a mountain bike with a quaint metal basket; at the time, he had never owned a car. The next interview unfolded during the following summer and stretched over two days at Powers’s small house in Urbana, surrounded by flowers, located on a leafy, tree-lined lane. Then, in December 2002, Powers talked on the phone from Urbana about The Time of Our Singing. While writing it, he said, something “so unexpectedly lucky happened at such a relatively late period in life” that he was able to tap a “new sense of stamina and sufficiency, of patience and confidence” to finish the book: he got married for the first time.

For all of his high-octane intellect, Powers remains charming and gracious in conversation, seriously and precisely elucidating his fiction with levity and laughter.

INTERVIEWER

When did you begin your writing career?

RICHARD POWERS

In the early eighties, I was living in the Fens in Boston right behind the Museum of Fine Arts. If you got there before noon on Saturdays, you could get into the museum for nothing. One weekend, they were having this exhibition of a German photographer I’d never heard of, who was August Sander. It was the first American retrospective of his work. I have a visceral memory of coming in the doorway, banking to the left, turning up, and seeing the first picture there. It was called Young Westerwald Farmers on Their Way to a Dance, 1914. I had this palpable sense of recognition, this feeling that I was walking into their gaze, and they’d been waiting seventy years for someone to return the gaze. I went up to the photograph and read the caption and had this instant realization that not only were they not on the way to the dance, but that somehow I had been reading about this moment for the last year and a half. Everything I read seemed to converge onto this act of looking, this birth of the twentieth century—the age of total war, the age of the apotheosis of the machine, the age of mechanical reproduction. That was a Saturday. On Monday I went in to my job and gave two weeks notice and started working on Three Farmers.

INTERVIEWER

What did you do for money?

POWERS

I had been working doing computer operations for a credit union. It was a terrific time to be a programmer because there was so much demand that you could make a living as a freelancer. You could pick up a six-week job, build a war chest, go write, and after a few months come crawling back out and look for another short-term job. Once I worked for an exiled Spanish prince. He was the grandson of the old king before Spain’s civil war, which I guess made him a cousin to Juan Carlos. He had been in line to head the restoration, and when it went against him he ended up in the United States as a trader. Here was this socialist royal trying to find out ways of building options spreads. So I wrote one of the very first real-time options-hedge trading programs.

INTERVIEWER

You should have stayed with it. You might have been a billionaire by now.

POWERS

I had a book to write.

INTERVIEWER

Where do your stories start?

POWERS

A stray account about the gold rush to crack the genetic code or meeting David Rumelhart, the father of neural networks, at a conference in Chicago and having him describe these bizarre machines to me years before the public ever heard about them. Plowing the Darkstarted when I heard a lecture by Terry Waite, who told about his five-year captivity in Beirut. After the lecture, he took questions from the audience and someone bluntly asked, What was the main thing you learned in being locked up for five years? In the moment after my stomach lurched at the question, I ran through all the possible answers: love life while you can; never take people for granted again. But his answer was shocking. He said, Contemporary humanity has lost the ability to engage in productive solitude.

INTERVIEWER

What do you think he meant by productive?

POWERS

He wasn’t using the term in the way late-capitalistic market society would mean productive. He wasn’t talking about General Motors’s definition of productivity. The currency he was speaking of is very much the care and tending of individual salvation.

To me, his comment legitimized the process of reading and writing. The thing that makes reading and writing suspect in the eyes of the market economy is that it’s not corrupted. It’s a threat to the GNP, to the gene engineer. It’s an invisible, sedate, almost inert process. Reading is the last act of secular prayer. Even if you’re reading in an airport, you’re making a womb unto yourself—you’re blocking the end results of information and communication long enough to be in a kind of stationary, meditative aspect. A book is a done deal and nothing you do is going to alter the content, and that’s antithetical to the idea that drives our society right now, which is about changing the future, being an agent, getting and taking charge of your destiny and altering it. The destiny of a written narrative is outside the realm of the time. For so long as you are reading, you are also outside the realm of the time. What Waite said seemed like a justification for this unjustifiable process that I’ve given my life to.

INTERVIEWER

There’s a great line in Galatea 2.2: “The loneliness of writing is that you baffle your friends and change the lives of strangers.”

POWERS

I think that quote sums up nicely the sort of paradoxical relationship that the fiction writer takes toward the world. You remove yourself from the world in order to have control over the ways of depicting it. And the crisis of representation is exactly that. Are you killing the thing by freezing it in the representation? I’m reminded of a line in Proust: “The hermit is the person to whom the judgment of a society matters the most.” And therefore he removes himself from the domain of the social in order to protect himself from that judgment.

What strikes me when you talk to writers about the writing process is the incredibly anxious and ongoing battle between the inside and the outside—the struggle to solve being in the world sufficiently to feel what’s really going on, and being out of the world sufficiently to be able to protect yourself from what’s going on. Then to be able to assemble it in a removed and protected and safe environment. You constantly hear these stories about people like Turgenev sitting by a window, which had to be closed, with his feet in hot water. It’s a very elaborate balancing act to find a necessary womb that isn’t so far removed from the world of stimuli that it gets choked off at the root, and yet isn’t in the maelstrom. You want to see and feel the maelstrom but not be buffeted by it.