Issue 95, Spring 1985

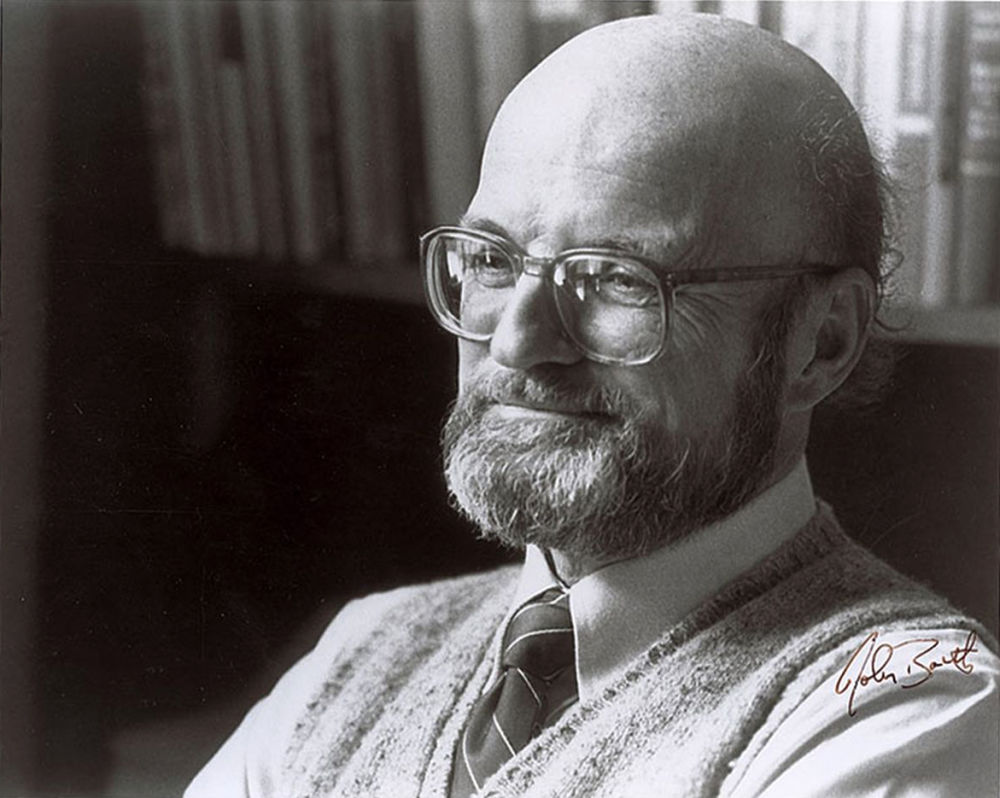

This interview with John Barth was conducted in the studios of KUHT in Houston, Texas, for a series entitled The Writer in Society. The stage set was made up to resemble a writer’s den—the decor including a small globe of the world, bronze Remington-like animal statuary, a stand-up bookshelf with glass shelves on which were placed some potted plants and a haphazard collection of books, a few volumes of the Reader’s Digest condensed novel series among them. Large pots of plants were set about. Barth sat amongst them in a cane chair. He is a tall man with a domed forehead; a pair of very large-rimmed spectacles give him a professorial, owlish look. He is a caricaturist’s delight. He sports a very wide and straight mustache. Recently he had grown a beard. In manner, Barth has been described as a combination of British officer and Southern gentleman.

“We’ll have to stick to the channel,” he wrote in his first novel, The Floating Opera, “and let the creeks and coves go by.” Every novel since then has been a refutation of this dictum of sticking to the main topic. He is especially influenced by the classical cyclical tales such as Burton’s Thousand and One Nights and the Gesta Romanorum, and by the complexities of such modern masters as Nabokov, Borges, and Beckett. For novels distinguished by a wide range of erudition, invention, wit, historical references, whimsy, bawdiness, and a great richness of image and style, Barth has been described as an “ecologist of information.”

Of his working habits Barth has said that he rises at six in the morning and puts an electric percolator in the kitchen so that during the course of sitting for six hours at his desk he has an excuse for the exercise of walking back and forth from his study to the kitchen for a cup of coffee. He speaks of measuring his work not by the day (as Hemingway did) but by the month and the year. “That way you don’t feel so terrible if you put in three days straight without turning up much of anything. You don’t feel blocked.”

This interview, being restricted to a half-hour’s conversation for a television audience, was thought to be a bit short by the usual standards of the magazine. It was assumed that Barth, being such a master of the prolix, would surely make some additions. Extra questions were sent him. The interview was returned to these offices with the questions unanswered, and the text of the interview edited and shortened. Perhaps Barth had not noticed the additional questions. This interview was sent back, this time with a small emolument attached for taking the trouble. The interview was returned once again, along with the uncashed check, with the following statement: “It doesn’t displease me to hear that our interview will be perhaps the shortest one you’ve run. In fact, it’s a bit shorter now than it was before (enclosed). Better not run it by me again!”

INTERVIEWER

When were the first stirrings? When did you actually understand that writing was going to be your profession? Was there a moment?

JOHN BARTH

It seems to happen later in the lives of American writers than Europeans. American boys and girls don’t grow up thinking, “I’m going to be a writer,” the way we’re told Flaubert did; at about age twelve he decided he would be a great French writer and, by George, he turned out to be one. Writers in this country, particularly novelists, are likely to come to the medium through some back door. Nearly every writer I know was going to be something else, and then found himself writing by a kind of passionate default. In my case, I was going to be a musician. Then I found out that while I had an amateur’s flair, I did not have preprofessional talent. So I went on to Johns Hopkins University to find something else to do. There I found myself writing stories—making all the mistakes that new writers usually make. After I had written about a novel’s worth of bad pages, I understood that while I was not doing it well, that was the thing I was going to do. I don’t remember that realization coming as a swoop of insight, or as an exhilarating experience, but as a kind of absolute recognition that for well or for ill, that was the way I was going to spend my life. I had the advantage at Johns Hopkins of a splendid old Spanish poet-teacher, with whom I read Don Quixote. I can’t remember a thing he said about Don Quixote, but old Pedro Salinas, now dead, a refugee from Franco’s Spain, embodied to my innocent, ingenuous eyes, the possibility that a life devoted to the making of sentences and the telling of stories can be dignified and noble. Whether the works have turned out to be dignified and noble is another question, but I think that my experience is not uncommon: You decide to be a violinist, you decide to be a sculptor or a painter, but you find yourself being a novelist.

INTERVIEWER

What was the musical instrument you started out with?

BARTH

I played drums. What I hoped to be eventually was an orchestrator—what in those days was called an arranger. An arranger is a chap who takes someone else’s melody and turns it to his purpose. For better or worse, my career as a novelist has been that of an arranger. My imagination is most at ease with an old literary convention like the epistolary novel, or a classical myth—received melody lines, so to speak, which I then reorchestrate to my purpose.

INTERVIEWER

What’s first when you sit down to begin a novel? Is it the form, as in the epistolary novel, or character, or plot?

BARTH

Different books start in different ways. I sometimes wish that I were the kind of writer who begins with a passionate interest in a character and then, as I’ve heard other writers say, just gives that character elbowroom and sees what he or she wants to do. I’m not that kind of writer. Much more often I start with a shape or form, maybe an image. The floating showboat, for example, which became the central image in The Floating Opera, was a photograph of an actual showboat I remember seeing as a child. It happened to be named Captain Adams’ Original Unparalleled Floating Opera, and when nature, in her heavy-handed way, gives you an image like that, the only honorable thing to do is to make a novel out of it. This may not be the most elevated of approaches. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, for example, comes to the medium of fiction with a high moral purpose; he wants, literally, to try to change the world through the medium of the novel. I honor and admire that intention, but just as often a great writer will come to his novel with a much less elevated purpose than wanting to undermine the Soviet government. Henry James wanted to write a book in the shape of an hourglass. Flaubert wanted to write a novel about nothing. What I’ve learned is that the muses’ decision to sing or not to sing is not based on the elevation of your moral purpose—they will sing or not regardless.

INTERVIEWER

What was in your way that you had to get out of your way?

BARTH

What was in my way? Chekhov makes a remark to his brother, the brother he was always hectoring in letters, “What the aristocrats take for granted, we pay for with our youth.” I had to pay my tuition in literature that way. I came from a fairly unsophisticated family from the rural, southern Eastern Shore of Maryland—which is very “deep South” in its ethos. I went to a mediocre public high school (which I enjoyed), fell into a good university on a scholarship, and then had to learn, from scratch, that civilization existed, that literature had been going on. That kind of innocence is the reverse of the exquisite sophistication with which a writer like Vladimir Nabokov comes to the medium—knowing it already, as if he’s been in on the conversation since it began. Yet the innocence that writers like myself have to overcome, if it doesn’t ruin us altogether, can become a sort of strength. You’re not intimidated by your distinguished predecessors, the great literary dead. You have a chutzpah in your approach to the medium that may carry you through those apprentice days when nobody’s telling you you’re any good because you aren’t yet. Everything is a discovery. I read Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn when I was about twenty-five. If I had read it when I was nineteen, I might have been intimidated; the same with Dickens and other great novelists. In my position I remained armed with a kind of “invincible innocence”—I think that’s what the Catholics call it—that with the best of fortune can survive even later experience and sophistication and carry you right to the end of the story.