Issue 121, Winter 1991

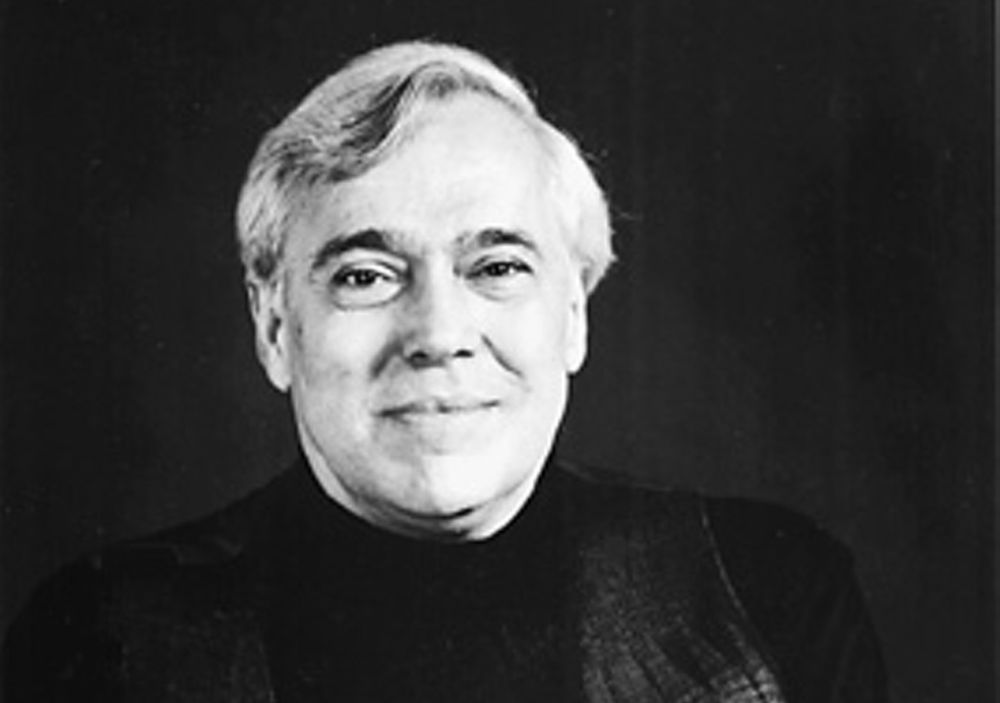

“Cities are the least permanent things in our civilization,” according to Reynolds Price, who has centered both his life and his literary work around the rural and small-town culture of the American South. Born in Macon, North Carolina in 1933, he has spent most of his life in his home state, though he has traveled widely. He studied at Duke University as an undergraduate and earned his B. Litt. at Oxford’s Merton College after winning a Rhodes scholarship. In 1958 he returned to Duke to join the faculty of the English department, becoming in 1977 James B. Duke Professor of English. Except for temporary posts as writer in residence at other universities, Price has remained at Duke, where he currently teaches for one semester each year.

In the thirty years of his literary career, Price—as novelist, short-story writer, poet, playwright, essayist and translator— has published twenty-one books, twenty with Atheneum, the publisher of his highly acclaimed first novel, A Long and Happy Life (1962), winner of the William Faulkner and Sir Walter Raleigh awards. Among the novels for which Price is best known are The Surface of Earth (1975), which won the Lillian Smith Award, and Kate Vaiden(1986), for which he was awarded the National Book Critics Circle Award. His short stories have been included in Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards and The Best American Short Stories. He has held Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, and in 1988 became a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

This interview was conducted on November 19, 1990 at the 92nd Street YM-YWHA in New York City in front of a large audience. Though Price has been confined to a wheelchair since 1984, when he underwent the first of three operations for spinal cancer, he is still a muscular, energetic man. As an artist he has remained unfettered and is, if anything, more prolific now than ever. (A novel Blue Calhoun and a collection of short stories are forthcoming in 1992 and 1993.) After the interview, Price read from his poems and new fiction. The atmosphere was warm, even familial. At the end of the reading he lifted himself up on the arms of his wheelchair and, on locked elbows, bowed to acknowledge the applause.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s start with the recent and important past. In 1984 you fought an astrocytoma in your spinal cord. Since then you have rolled on to produce the following: Kate Vaiden, The Laws of Ice, A Common Room, Good Hearts, Clear Pictures, The Tongues of Angels, New Music, and The Use of Fire. You have published poems, essays, plays, novels, novellas, translations. Can you talk about your extraordinary prolificness?

REYNOLDS PRICE

No, I can’t—not confidently. My mother had an all-purpose word for any mysterious anatomical reality. She called it an epizootic. So I always say that the X-ray treatments must have speeded up my epizootic, but that’s about all I can offer. One very practical thing that’s happened though is that I’ve had the enormous luck to have, since 1984, one reliable assistant at a time who has lived in my home and has done the kinds of daily chores that are no longer easy for me—groceries and mail and so forth. I’ve learned what an immense amount of human energy is eaten up by going to get the laundry, much less washing and folding it. I have that much more time available in the day now, but something much larger and stranger has also happened, and I can’t say what it is, though I’m grateful.

INTERVIEWER

It’s clearly not just opportunity. Are you compelled to write?

PRICE

I’m compelled in a very invigorating way to write. It’s not some Dostoyevskian ax-murderer compulsion to spend the day at the keyboard. No, I love to do it.

INTERVIEWER

You’re not just staying out of trouble?

PRICE

Not just that, by any means, though idleness quickly poisons me if I let it spread. You’ve mentioned the crisis of 1984 to 1986 when spinal cancer, three radical surgeries, and five weeks of withering radiation paralyzed my legs. In the first five months of that long dark night, I couldn’t write more than the odd short poem. My mind and hands just would not do it. I couldn’t even make myself read, not more than letters or magazines. I was, at first, deeply stunned and then intent in every cell on healing and lasting. Only when a friend, uncoached by me, commissioned me to write a play for a group of young actors, was I slowly able to guess that I was free again to focus my attention on something more than my own halved body and its secret inner guerrilla campaign to save what was left, then teach it a whole new life, strange as Mars. In slow motion I wrote a play called August Snow through the next two months; and that time warmed my engine enough to send me straight back to finish Kate Vaiden, which I’d abandoned at the end of part one, and then on through the eleven books I’ve started and finished in the past six years. Previously I’d averaged a book every two years at least, so I’d hardly been a great tree sloth; but I’d always said truthfully that writing was hard for me, very hard, and now it’s not.

INTERVIEWER

Are you having fun?

PRICE

At this instant?

INTERVIEWER

No! Are you having fun as a writer? Most writers would not admit that they are.

PRICE

Well, I don’t want to talk about “the joy of writing” as in “the joy of sex.” But it’s a deep joy, yes. I like it better than anything else I do except being with a small group of very dear friends, and sometimes I have to skedaddle from them and go back and write for a while.

INTERVIEWER

Let’s go back to when you were a very young child. You were a gifted artist using pen, pencil, and paint. In your recent novel, The Tongues of Angels, your narrator-hero is an artist. Seeing and turning what you see into something tangible is very important to you. How does the visual intermingle with your obvious love of language?

PRICE

First, my eyes are my primary teachers. And I assume that this is true for a vast percentage of the human race, certainly for the entire sighted portion. For us, the world enters there—it mainly enters my mind through my eyes, and I make of it what I will and can. The granary, the silo—my garnered experience—begins as stored visual observation. I tell my writing students constantly that roughly ninety-five percent of the human race is legally blind, and I mean it quite literally. You don’t have to be in New York to realize that Americans never see anything; you can go to a small country town and realize that an enormous number of the citizens simply don’t see anything at any given moment but what they are actually hoping to see.

For some reason or other I was born an avid observer and witness. Both my parents were tremendous watchers of the world. I can remember from my childhood that one of the things my mother loved most was just to drive downtown, park, and sit in the car watching people walk by. Europeans and Middle Easterners do that in their piazzas and souks. Of course, if we try it now in Bryant Park or Central Park, we’re dead by sundown. But I love to watch the world, and that visual experience becomes, in a way I couldn’t begin to chart or describe, the knowledge I possess; that knowledge produces whatever it is that I write. From the very beginning of my serious adult work, when I was a senior in college, my writing has emerged by a process over which I have almost no more conscious control than over the growth of my fingernails. The best I can do is to live as if I were training for the Olympics. I try to keep my mind, which is an organ of something called my body, in the best possible physical shape; if I do that, I find that it does my work for me. I think artists of almost all sorts would say that—from great athletes and dancers to poets and composers. There’s a huge amount of discipline and training and specific technique that can be learned; but ultimately it’s a matter of arriving each morning at the desk and finding that the cistern filled up in the night—or that it didn’t, which is mostly my fault.

INTERVIEWER

And that no one will rescue you from having to do something about it.

PRICE

Absolutely. Man the bilge pumps or dig for water!