Issue 124, Fall 1992

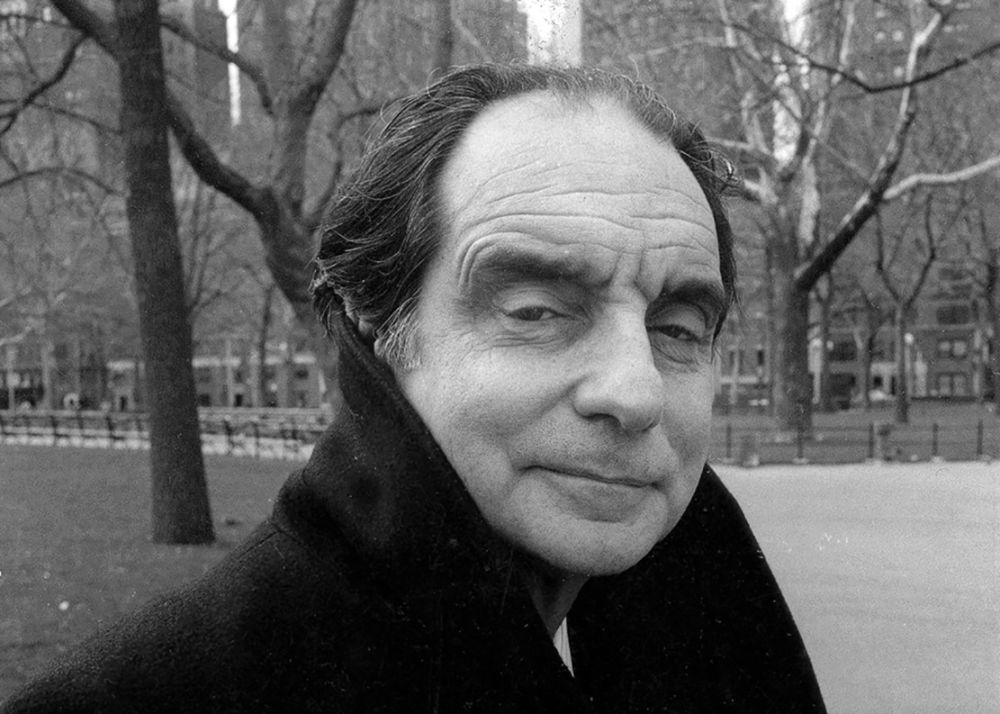

Upon hearing of Italo Calvino’s death in September of 1985, John Updike commented, “Calvino was a genial as well as brilliant writer. He took fiction into new places where it had never been before, and back into the fabulous and ancient sources of narrative.” At that time Calvino was the preeminent Italian writer, the influence of his fantastic novels and stories reaching far beyond the Mediterranean.

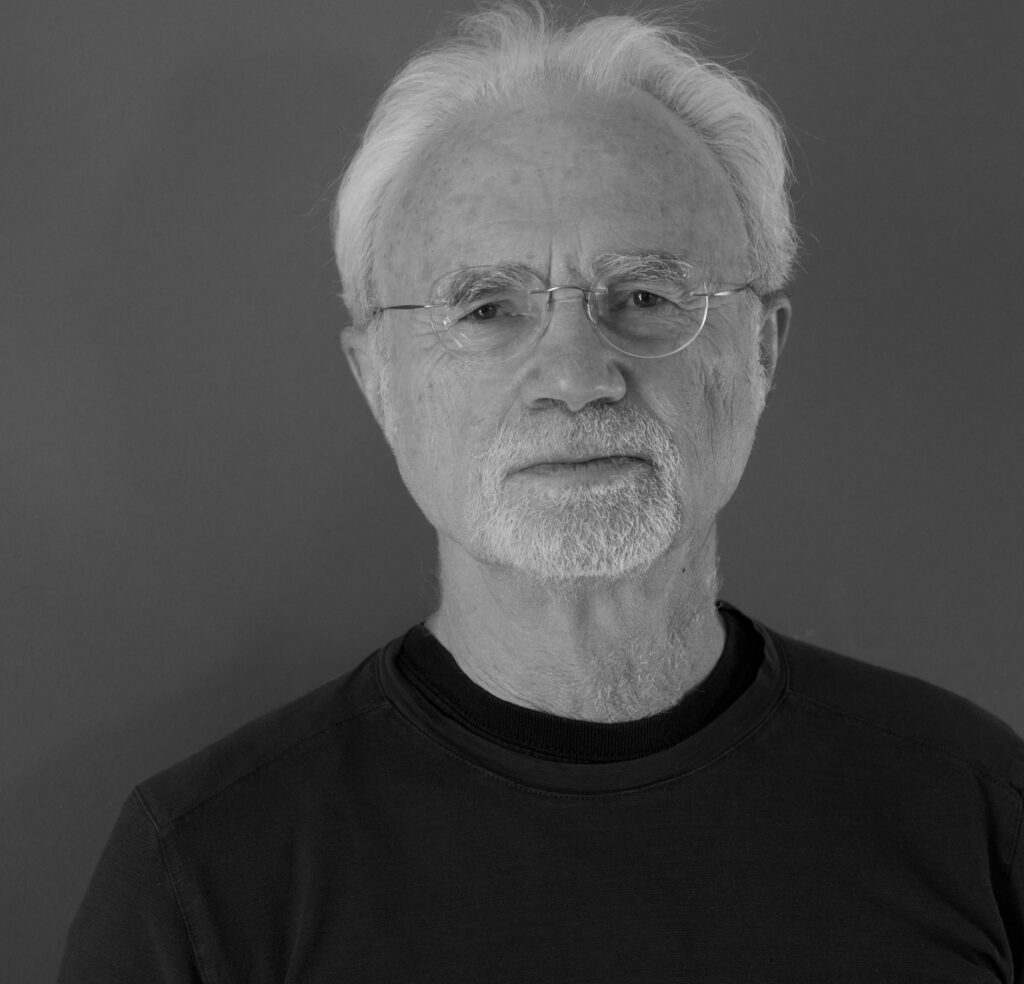

Two years before, The Paris Review had commissioned a Writers at Work interview with Calvino to be conducted by William Weaver, his longtime English translator. It was never completed, though Weaver later rewrote his introduction as a remembrance. Still later, The Paris Review purchased transcripts of a videotaped interview with Calvino (produced and directed by Damien Pettigrew and Gaspard Di Caro) and a memoir by Pietro Citati, the Italian critic. What follows—these three selections and a transcript of Calvino’s thoughts before being interviewed—is a collage, an oblique portrait.

—Rowan Gaither, 1992

Italo Calvino was born on October 15, 1923 in Santiago de Las Vegas, a suburb of Havana. His father Mario was an agronomist who had spent a number of years in tropical countries, mostly in Latin America. Calvino’s mother Eva, a native of Sardinia, was also a scientist, a botanist. Shortly after their son’s birth, the Calvinos returned to Italy and settled in Liguria, Professor Calvino’s native region. As Calvino grew up, he divided his time between the seaside town of San Remo, where his father directed an experimental floriculture station, and the family’s country house in the hills, where the senior Calvino pioneered the growing of grapefruit and avocados.

The future writer studied in San Remo and then enrolled in the agriculture department of the University of Turin, lasting there only until the first examinations. When the Germans occupied Liguria and the rest of northern Italy during World War II, Calvino and his sixteen-year-old brother evaded the Fascist draft and joined the partisans.

Afterward, Calvino began writing, chiefly about his wartime experiences. He published his first stories and at the same time resumed his university studies, transferring from agriculture to literature. During this time he wrote his first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders, which he submitted to a contest sponsored by the Mondadori publishing firm. The novel did not place in the competition, but the writer Cesare Pavese passed it on to the Turin publisher Giulio Einaudi who accepted it, establishing a relationship with Calvino that would continue throughout most of his life. When The Path to the Nest of Spiders appeared in 1947, the year that Calvino took his university degree, he had already started working for Einaudi.

In the postwar period the Italian literary world was deeply committed to politics, and Turin, an industrial capital, was a focal point. Calvino joined the Italian Communist Party and reported on the Fiat company for the party’s daily newspaper.

After the publication of his first novel, Calvino made several stabs at writing a second, but it was not until 1952, five years later, that he published a novella, The Cloven Viscount. Sponsored by Elio Vittorini and published in a series of books by new writers called Tokens, it was immediately praised by reviewers, though its departure from the more realistic style of his first novel resulted in criticism from the party, from which he resigned in 1956 when Hungary was invaded by the Soviet Union.

In 1956 Calvino published a seminal collection of Italian folktales. The following year he brought out The Baron in the Trees, and in 1959 The Nonexistent Knight. These two stories, with The Cloven Viscount, have been collected in the volume Our Ancestors. In 1965 he published Cosmicomics, and in 1979 his novel (or antinovel) If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler appeared. The last works published during his lifetime were Mr. Palomar (1983), a novel, and Difficult Loves (1984), a collection of stories.

Calvino died on September 19, 1985 in a hospital in Siena, thirteen days after suffering a stroke.

I first met Italo Calvino in a bookshop in Rome, sometime in the spring of 1965—my memory-picture has us both wearing light suits. I had been living in Rome for well over a decade. Calvino had returned to the city only a short time before, after a long period in Paris. He asked me abruptly—he was never a man for idle circumlocution—if I would like to translate his latest book, Cosmicomics. Though I hadn’t read it, I immediately said yes. I picked up a copy before leaving the store and we arranged to get together a few days later.

He was living with his family in a small, recently modernized apartment in the medieval quarter of the city near the Tiber. Like Calvino houses that I was to know later, the apartment gave the impression of being sparsely furnished; I remember the stark white walls, the flooding sunlight. We talked about the book, which I had read in the meanwhile. I learned that he had already tried out—and flunked—one English translator, and I wanted to know the reason for my colleague’s dismissal. Indiscreetly, Calvino showed me the correspondence. One of the stories in the volume was called “Without Colors.” In an excess of misguided originality, the translator had entitled the piece “In Black and White.” Calvino’s letter of dismissal pointed out that black and white are colors. I signed on.

My first translation of Calvino had a difficult history. The American editor who commissioned it changed jobs just as I was finishing, and—on my unfortunate advice— Calvino followed him to his new firm. But then the editor committed suicide, the new house turned down Cosmicomics, the old house wouldn’t have us back, and the book was adrift. It was rejected by other publishers, until Helen Wolff at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich accepted it, beginning Calvino’s long association with that publishing house. The book received glowing reviews (and one fierce pan from, predictably, the first translator) and won the National Book Award for translation.

From 1966 until his death there was hardly a time when I wasn’t translating (or supposed to be translating) something by him. On occasion he would call up and ask me to translate a few pages of text at top speed—a statement he had to make for a Canadian television program or a little introduction to a book on conduits. He loved strange assignments: the wondrous Castle of Crossed Destinies (1969) was born as a commentary on a Renaissance deck of tarot cards.

With Calvino every word had to be weighed. I would hesitate for whole minutes over the simplest word—bello (beautiful) or cattivo (bad). Every word had to be tried out. When I was translating Invisible Cities, my weekend guests in the country always were made to listen to a city or two read aloud.

Writers do not necessarily cherish their translators, and I occasionally had the feeling that Calvino would have preferred to translate his books himself. In later years he liked to see the galleys of the translation; he would make changes—in his English. The changes were not necessarily corrections of the translation; more often they were revisions, alterations of his own text. Calvino’s English was more theoretical than idiomatic. He also had a way of falling in love with foreign words. With the Mr. Palomar translation he developed a crush on the word feedback. He kept inserting it in the text and I kept tactfully removing it. I couldn’t make it clear to him that, like charisma and input and bottom line, feedback, however beautiful it may sound to the Italian ear, was not appropriate in an English-language literary work.

One August afternoon in 1982, I drove to Calvino’s summer house—a modern, roomy villa in a secluded residential complex at Roccamare on the Tuscan sea coast north of Grosseto. After exchanging greetings, we settled down in big comfortable chairs on the broad shaded terrace. The sea was not visible, but you could sense it through the pungent, pine-scented air.

Calvino most of the time was not a talkative man, never particularly sociable. He tended to see the same old friends, some of them associates from Einaudi. Though we had known each other for twenty years, went to each other’s houses, and worked together, we were never confidants. Indeed, until the early 1980s we addressed each other with the formal lei; I called him Signor Calvino and he called me Weaver, unaware how I hated being addressed by my surname, a reminder of my dread prep-school days. Even after we were on first-name terms, when he telephoned me I could sense a pause before his “Bill?” He was dying to call me Weaver as in the past.

I don’t want to give the impression that he couldn’t be friendly. Along with his silences, I remember his laughter, often sparked by some event in our work together. And I remember a present he gave me, an elegant little publication about a recently restored painting by Lorenzo Lotto of St. Jerome. Inside, Calvino wrote, “For Bill, the translator as saint.”

Still, thinking back on it, I always felt somewhat the intruder.

—William Weaver

Thoughts Before an Interview

Every morning I tell myself, Today has to be productive—and then something happens that prevents me from writing. Today . . . what is there that I have to do today? Oh yes, they are supposed to come interview me. I am afraid my novel will not move one single step forward. Something always happens. Each morning I already know I will be able to waste the whole day. There is always something to do: go to the bank, the post office, pay some bills . . . always some bureaucratic tangle I have to deal with. While I am out I also do errands such as the daily shopping: buying bread, meat, or fruit. First thing, I buy newspapers. Once one has bought them, one starts reading as soon as one is back home—or at least looking at the headlines to persuade oneself that there is nothing worth reading. Every day I tell myself that reading newspapers is a waste of time, but then . . . I cannot do without them. They are like a drug. In short, only in the afternoon do I sit at my desk, which is always submerged in letters that have been awaiting answers for I do not even know how long, and that is another obstacle to be overcome.

Eventually I get down to writing and then the real problems begin. If I start something from scratch, that is the most difficult moment, but even if it is something I started the day before, I always reach an impasse where a new obstacle needs to be overcome. And it is only in the late afternoon that I finally begin to write sentences, correct them, cover them with erasures, fill them with incidental clauses, and rewrite. At that very moment the telephone or doorbell usually rings and a friend, translator, or interviewer arrives. Speaking of which . . . this afternoon . . . the interviewers . . . I do not know if I will have the time to prepare. I could try to improvise but I believe an interview needs to be prepared ahead of time to sound spontaneous. Rarely does an interviewer ask questions you did not expect. I have given a lot of interviews and I have concluded that the questions always look alike. I could always give the same answers. But I believe I have to change my answers because with each interview something has changed either inside myself or in the world. An answer that was right the first time may not be right again the second. This could be the basis of a book. I am given a list of questions, always the same; every chapter would contain the answers I would give at different times. The changes would contain the answers I would give at different times. The changes would then become the itinerary, the story that the protagonist lives. Perhaps in this way I could discover some truths about myself.

But I must go home—the time approaches for the interviewers to arrive.

God help me!

—Italo Calvino

INTERVIEWER

What place, if any at all, does delirium have in your working life?

ITALO CALVINO

Delirium? . . . Let’s assume I answer, I am always rational. Whatever I say or write, everything is subject to reason, clarity, and logic. What would you think of me? You’d think I’m completely blind when it comes to myself, a sort of paranoiac. If on the other hand I were to answer, Oh, yes, I am really delirious; I always write as if I were in a trance, I don’t know how I write such crazy things, you’d think me a fake, playing a not-too-credible character. Maybe the question we should start from is what of myself do I put into what I write. My answer—I put my reason, my will, my taste, the culture I belong to, but at the same time I cannot control, shall we say, my neurosis or what we could call delirium.

INTERVIEWER

What is the nature of your dreams? Are you more interested in Jung than you are in Freud?

CALVINO

Once after reading Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, I went to bed. I dreamt. The following morning I could remember perfectly my dream, so I was able to apply Freud’s method to my dream and explain it to the very last detail. At that moment I believed that a new era for me was about to begin; from that moment on my dreams would no longer keep any secrets from me. It didn’t happen. That was the only time Freud had ever lit the darkness of my subconscious. Since that time I have continued to dream as I did before. But I forget them, or if I’m able to remember them I don’t understand even the first things about them. To explain the nature of my dreams wouldn’t satisfy a Freudian analyst any more than a Jungian. I read Freud because I find him an excellent writer . . . a writer of police thrillers that can be followed with great passion. I also read Jung, who’s interested in things of great interest to a writer such as symbols and myths. Jung is not as good a writer as Freud. But, anyhow, I am interested in both of them.

INTERVIEWER

The images of fortuna and chance recur quite frequently in your fiction, from the shuffling of the tarot cards to the random distribution of manuscripts. Does the notion of chance play a role in the composition of your works?

CALVINO

My tarot book, The Castle of Crossed Destinies, is the most calculated of all I have written. Nothing in it is left to chance. I don’t believe chance can play a role in my literature.

INTERVIEWER

How do you write? How do you perform the physical act of writing?

CALVINO

I write by hand, making many, many corrections. I would say I cross out more than I write. I have to hunt for words when I speak, and I have the same difficulty when writing. Then I make a number of additions, interpolations, that I write in a very tiny hand. There comes a moment when I myself can’t read my handwriting, so I use a magnifying glass to figure out what I’ve written. I have two different handwritings. One is large with fairly big letters—the os and as have a big hole in the center. This is the hand I use when I’m copying or when I’m rather sure of what I’m writing. My other hand corresponds to a less confident mental state and is very small—the os are like dots. This is very hard to decipher, even for me.

My pages are always covered with canceling lines and revisions. There was a time when I made a number of handwritten drafts. Now, after the first draft, written by hand and completely scrawled over, I start typing it out, deciphering as I go. When I finally reread the typescript, I discover an entirely different text that I often revise further. Then I make more corrections. On each page I try first to make my corrections with a typewriter; I then correct some more by hand. Often the page becomes so unreadable that I type it over a second time. I envy those writers who can proceed without correcting.

INTERVIEWER

Do you work every day or only on certain days and at certain hours?

CALVINO

In theory I would like to work every day. But in the morning I invent every possible excuse not to work: I have to go out, make some purchases, buy the newspaper. As a rule, I manage to waste the morning, so I end up sitting down to write in the afternoon. I’m a daytime writer, but since I waste the morning I’ve become an afternoon writer. I could write at night, but when I do, I don’t sleep. So I try to avoid that.

INTERVIEWER

Do you always have a set task, something specific you decide to work on? Or do you have various things going on at once?

CALVINO

I always have a number of projects. I have a list of about twenty books I’d like to write, but then the moment comes when I decide I’m going to write that book. I’m only a novelist on occasion. Many of my books are made up of brief texts collected together, short stories, or else they are books that have an overall structure but are composed of various texts. Building a book around an idea is very important for me. I spend a lot of time constructing a book, making outlines that eventually prove to be of no use to me whatsoever. I throw them away. What determines the book is the writing, the material that’s actually on the page.

I’m very slow getting started. If I have an idea for a novel, I find every conceivable pretext to not work on it. If I’m doing a book of stories, short texts, each one has its own starting time. Even with articles I’m a slow starter. Even with articles for newspapers, every time I have the same trouble getting under way. Once I have started, then I can be quite fast. In other words, I write fast but I have huge blank periods. It’s a bit like the story of the great Chinese artist—the emperor asked him to draw a crab, and the artist answered, I need ten years, a great house, and twenty servants. The ten years went by, and the emperor asked him for the drawing of the crab. I need another two years, he said. Then he asked for a further week. And finally he picked up his pen and drew the crab in a moment, with a single, rapid gesture.

INTERVIEWER

Do you begin with a small group of unrelated ideas or a larger conception that you gradually fill in?

CALVINO

I start with a small, single image and then I enlarge it.