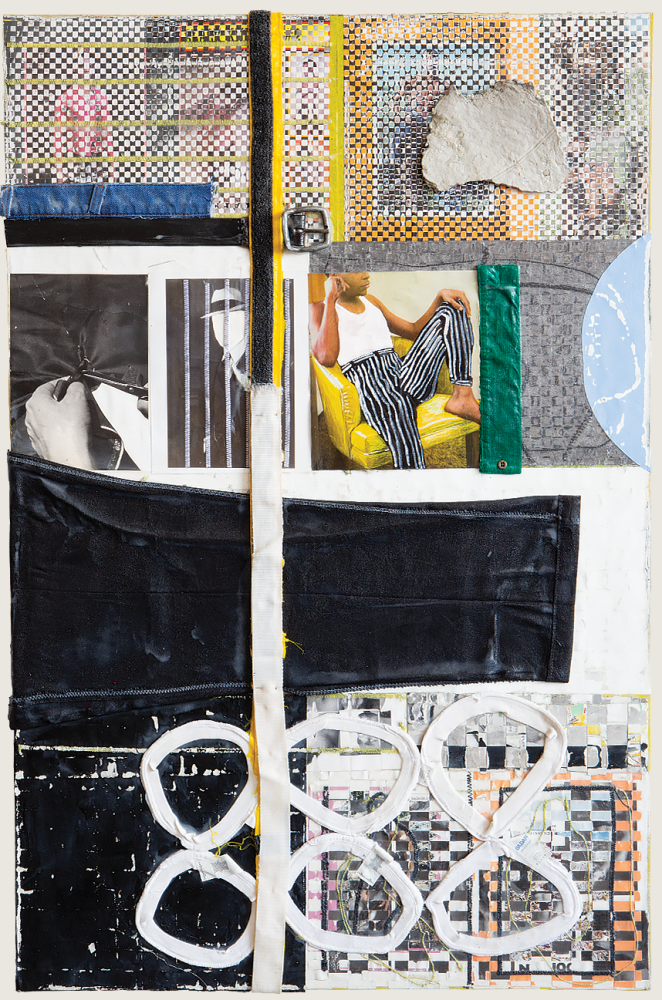

In the Margins, 2019, cut paper, polyester thread, papier-mâché, cut clothing, leather belt, fabric, tape, graphite, ink, colored pencil, acrylic, and woven paper on stretched linen, 48 x 33 x 1”.

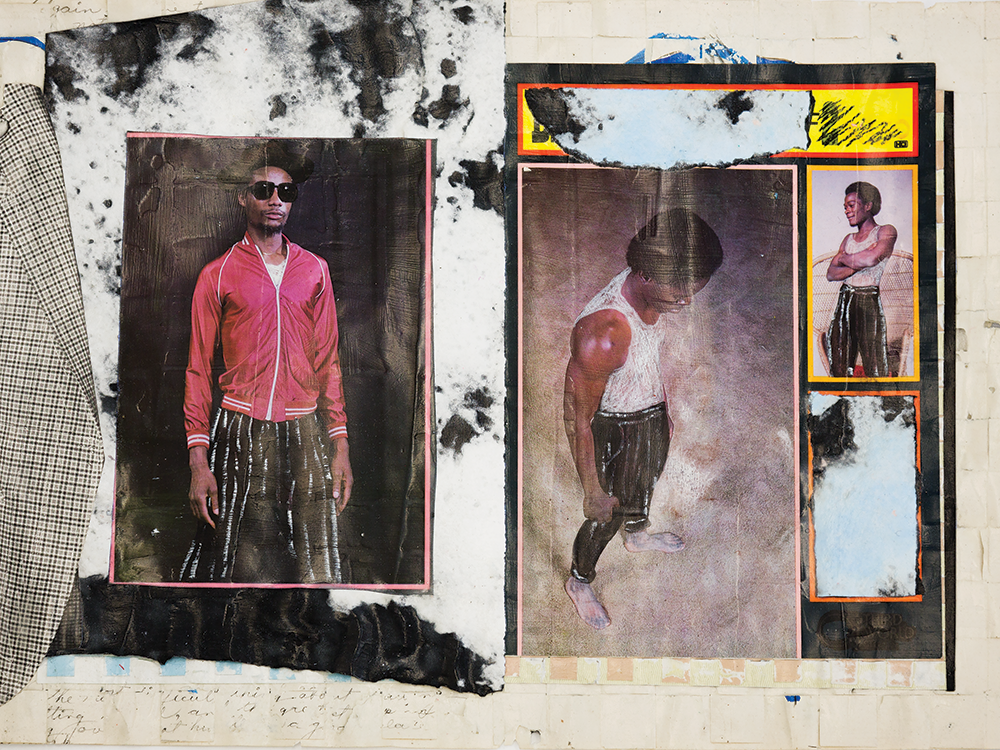

Interdisciplinary painter and collage artist Troy Michie (b. 1985) was raised in El Paso, Texas, and his work reflects the complexities of growing up multiracial along the U.S.-Mexico border. Michie began his formal training as a figurative painter and quickly brought collage elements onto his canvases. A central motif of these compositions is the Black male body—nude portraits, excised from vintage erotic magazines, appear frequently, often with clothes drawn onto them. A recent series examines the cultural history of the zoot suit in the Southwest, while other new pieces focus on the mysteries of the erotic male form: “There has to be something that isn’t totally easy to figure out,” Michie says. While the politics of representation of marginalized communities are a persistent theme, present, too, are formal considerations: many of Michie’s canvases rely on a nuanced approach to abstraction and color, and he relishes in the technical aspects of drawing, citing Mexican muralist José Clemente Orozco’s figurative work and Belgian painter René Magritte’s representational canvases as influences. Below, the artist speaks about his artistic development, in a conversation that has been edited.

—Emily Nemens

The atmosphere that I grew up in has played such a huge role in the way I see the world. When you grow up in a border community, it’s not abnormal to go to school with people from Mexico, or to speak Spanish, or to witness two cultures amalgamate, which ultimately I see as a collage.

I’ve been drawing since I was five. I was really interested in portraits, and I would draw my family, I would paint them. Meanwhile, a lot of my influences as a kid came from magazines—Lowrider and People—this was my view into popular culture. In undergrad it seemed like there was a division in disciplines, and I chose to become a painter. But I was always doing things to the paintings, which, I think, were notions of collage, I just didn’t know that could be an art form yet. It was seeing a piece by Frida Kahlo, who’s still one of my favorites, that opened my eyes. My Dress Hangs There (1933) features a clothesline with Frida’s Mexican dress. I remember seeing that the bottom portion was collaged with cutouts from newspapers, and thinking, Oh, I don’t have to just use paint. From there, artists like Mimmo Rotella and Jacques Villeglé introduced me to this idea of décollage. I was still making drawings, but then I’d glue them down to canvas and rip them off. There was something about adding my own history to the material and building up the layers over and over. It was liberating.

Many of my compositions seem a little formal, emphasizing geometric abstraction. I think a lot about delineation and boundaries. Oftentimes, when I’m crossing materials over another line or a grid that I’ve established, I’m considering the threshold of the border. But it’s important for me that it’s . . . I can’t really think of a better word than complicated. The work has always been related to portraiture, but recently the figure has come back into the foreground. For me, it’s a sort of a return to painting. There’s such an emphasis now on young Black painters painting Black figures—I’ve wanted to be included but still push up against and complicate that conversation.

Recently, my work has had an emphasis on the centerfold and woven pages, and I was searching for another compositional element. I’d never really worked with fabric before, other than gluing pieces into my assemblage works. While I’d been thinking about the possibility of stitching forever, I was just intimidated, mainly because I don’t know how to properly sew—I still don’t. A friend of mine had a machine, so I asked, Can you run this through the machine? And I was like, That’s it, that’s what has been missing in the work. It’s almost alchemical. Stitching is a way to bring in the language of drawing, to turn off the analytical side and draw some lines and make some marks. And there is also something poetic about it, in that the stitch is an attempt to bring something together. The stitch can be really strong, but it also falls apart all the time. It’s almost returning to this idea of the boundary—the created boundary—that is the Rio Grande, separating El Paso from Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. I think of this as another line, a stitch, a contour, a delineation, a boundary.

Three Men, 2019, cut paper, ink, and wax pencil on woven paper, 14 x 21 ¾ ”.