Mária Švarbová, Pool Only for Swimmers, 2016, digitally manipulated color photograph, 19 4/5 " x 19 4/5 ".

Mária Švarbová, Pool Only for Swimmers, 2016, digitally manipulated color photograph, 19 4/5 " x 19 4/5 ".

When I was little, I would paint water as a low blue stripe along the bottom of the paper. Not much different from the sky—a high blue stripe across the top. Maybe a darker blue. Then I learned how to swim and the waterline moved up, over my head. It became the whole page.

Here’s how my father taught me to swim: He would hold me, facing him, in the shallow end, then let go. He’d back away slowly, laughing and teasing as I tried to grab him. I would panic, inhale and swallow water, and laugh. It was horrible, like being tickled: alarming and exhilarating.

Water promises joy and fear. Looking at pictures of swimming is like looking at pictures of tenderness or violence—the body reacts, a sensibility beyond seeing. Some pictures evoke the smell of chlorine or the chill of water creeping up a rib cage, or rumbling bubbles underwater.

Like Narcissus, I see myself in swimmers. Narcissus fell in love with his reflection in a well and, according to some accounts, died when he dove into the water to embrace his own image. Other versions end with him starving to death at a pool’s edge.

My father took a picture of me when I was nine, in one of my first races. I’m not wearing a cap or goggles, my eyes are bloodshot, mouth gaping like a goldfish, I’m flinging my arms frantically as I near the cement edge of the pool. Later I learned I didn’t have to take my whole head out of the water to breathe. That I could carve a little eddy beside my shoulder with my bottom lip. That swimming is all exhaling.

I’ve always been unsettled by the Yeats poem “The Stolen Child” and

its refrain:

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

Not a poem about swimming, but about drowning.

Pictures of swimming have, suitably, an undercurrent. Of danger, of fun, of childhood, of being in over one’s head.

—Leanne Shapton

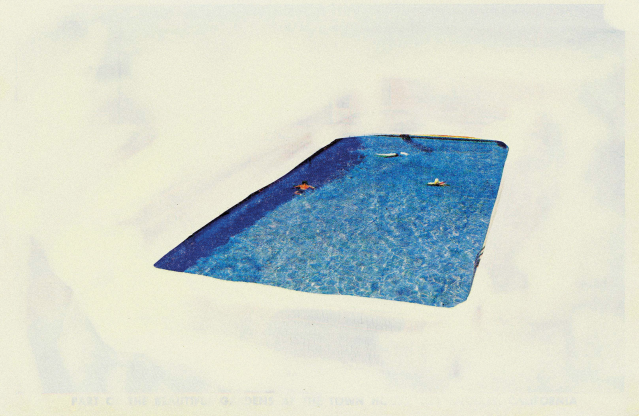

Leanne Shapton, The Castaways, Miami, 2012, house paint on paper, 3 1/2 " x 5 1/2 ".

Leanne Shapton, The Castaways, Miami, 2012, house paint on paper, 3 1/2 " x 5 1/2 ".

Leanne Shapton, Town House, LA, 2012, house paint on paper, 3 3/4 " x 5 1/2 ".

Leanne Shapton, Town House, LA, 2012, house paint on paper, 3 3/4 " x 5 1/2 ".

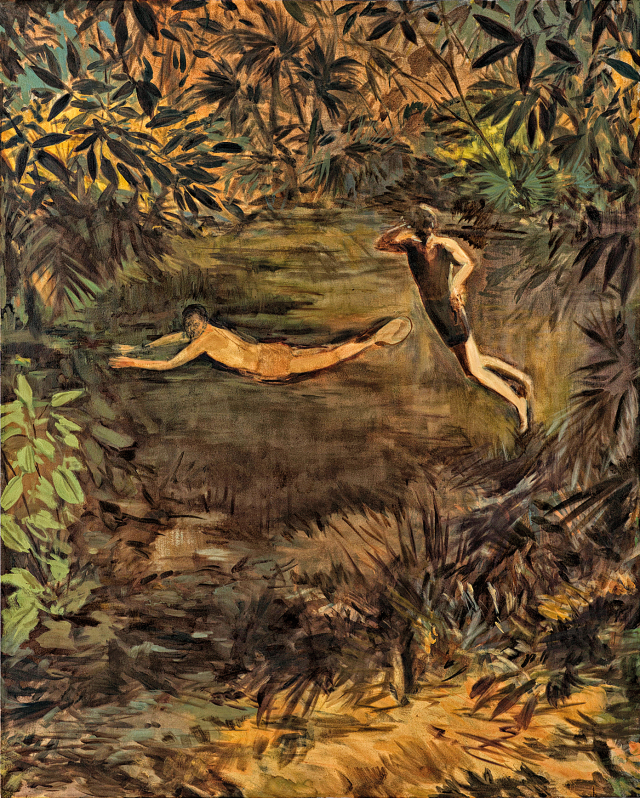

Jennifer Pochinski, The Big Swim, 2014, oil on canvas, 48 " x 52 ". Courtesy Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

Jennifer Pochinski, The Big Swim, 2014, oil on canvas, 48 " x 52 ". Courtesy Dolby Chadwick Gallery.

Nicolas Burrows, Lido, 2012, giclée print, 9 1/2 " x 12 1/2 ".

Nicolas Burrows, Lido, 2012, giclée print, 9 1/2 " x 12 1/2 ".

Oliver Spies, Le Plongeoir, 2014, laser print on photo paper, 39 2/5 " x 27 1/5 ". www.oliverspies.com

Oliver Spies, Le Plongeoir, 2014, laser print on photo paper, 39 2/5 " x 27 1/5 ". www.oliverspies.com

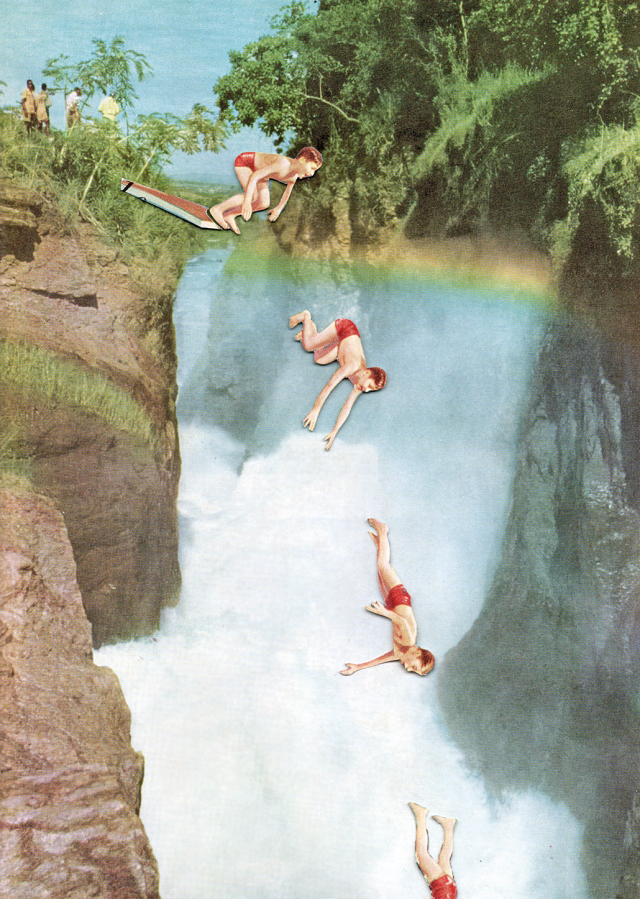

Randel Plowman, The Jump, 2014, collage, 4 3/4 " x 3 1/2 ".

Randel Plowman, The Jump, 2014, collage, 4 3/4 " x 3 1/2 ".

Marisa Keris, East of Eden, 2015, oil on canvas, 60 " x 48 ".

Marisa Keris, East of Eden, 2015, oil on canvas, 60 " x 48 ".

Amy Sherald, The Bathers, 2015, oil on canvas, 74 " x 72 ". Courtesy Monique Meloche Gallery.

Amy Sherald, The Bathers, 2015, oil on canvas, 74 " x 72 ". Courtesy Monique Meloche Gallery.

Joan Brown, The Bicentennial Champion, 1976, enamel on canvas, 96 " x 78 ". © Estate of Joan Brown. Image courtesy George Adams Gallery, New York. Photo Jay Oligny.

Joan Brown, The Bicentennial Champion, 1976, enamel on canvas, 96 " x 78 ". © Estate of Joan Brown. Image courtesy George Adams Gallery, New York. Photo Jay Oligny.

Ben Giles, Diving, 2012, collage, 10 " x 6 7/8 ".

Ben Giles, Diving, 2012, collage, 10 " x 6 7/8 ".

Rachel Levit Ruiz, Dancers, 2015, risograph, 4 1/8 " x 5 1/8 ".

Rachel Levit Ruiz, Dancers, 2015, risograph, 4 1/8 " x 5 1/8 ".

Zoë Taylor, Swimmer, 2009, ink and acrylic on paper, 8 1/4 " x 6 ".

Zoë Taylor, Swimmer, 2009, ink and acrylic on paper, 8 1/4 " x 6 ".

Jamie Tobin, Swimmers, 2013, gouache, watercolor, and pencil on paper, 16 1/2 " x 11 4/5 ".

Jamie Tobin, Swimmers, 2013, gouache, watercolor, and pencil on paper, 16 1/2 " x 11 4/5 ".

Richard Brocken, Swim, 2014, digital, 23 3/5 " x 35 2/5 ".

Richard Brocken, Swim, 2014, digital, 23 3/5 " x 35 2/5 ".

Alex Beck, Board, 2015, oil on panel, 24" x 24”.

Alex Beck, Board, 2015, oil on panel, 24" x 24”.

Sammy Slabbinck, Seafood, 2013, collage, 8 " x 10 ".

Sammy Slabbinck, Seafood, 2013, collage, 8 " x 10 ".

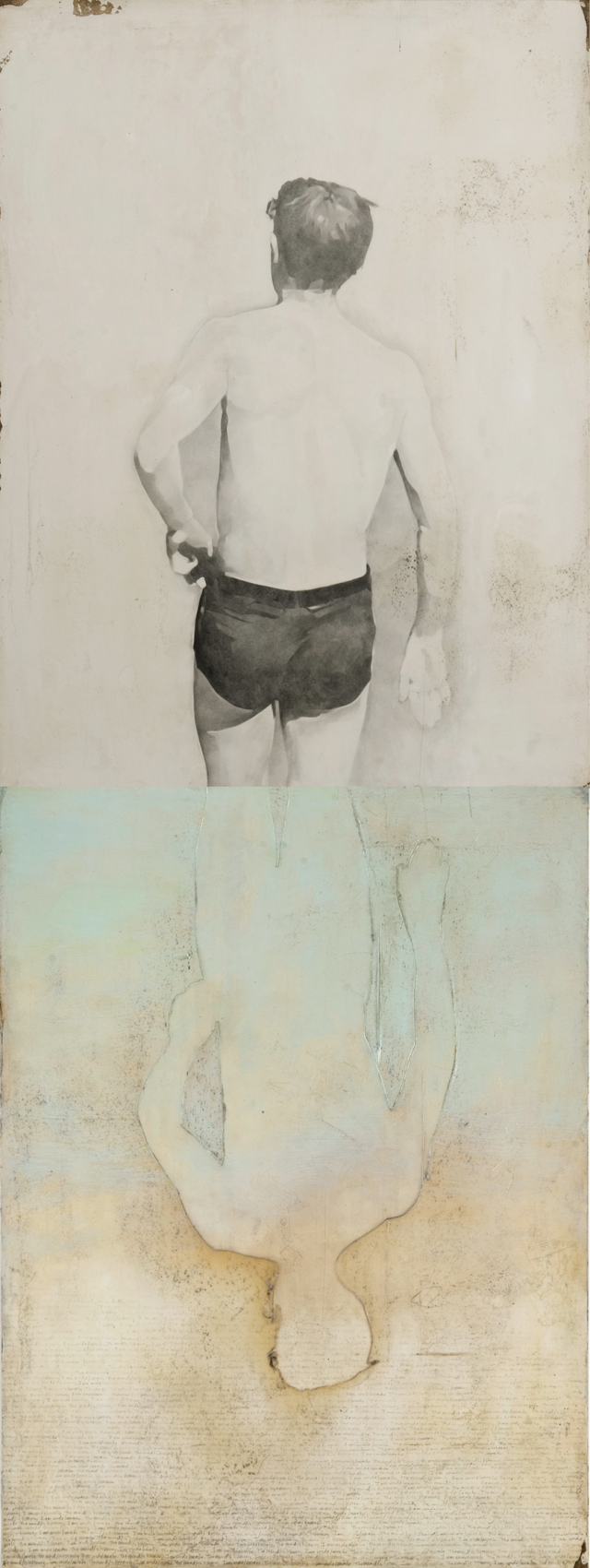

Jane Hambleton, Looking In, 2009, graphite, acrylic gel, acrylic, and oil on paper, 80 " x 30 ".

Jane Hambleton, Looking In, 2009, graphite, acrylic gel, acrylic, and oil on paper, 80 " x 30 ".