Issue 154, Spring 2000

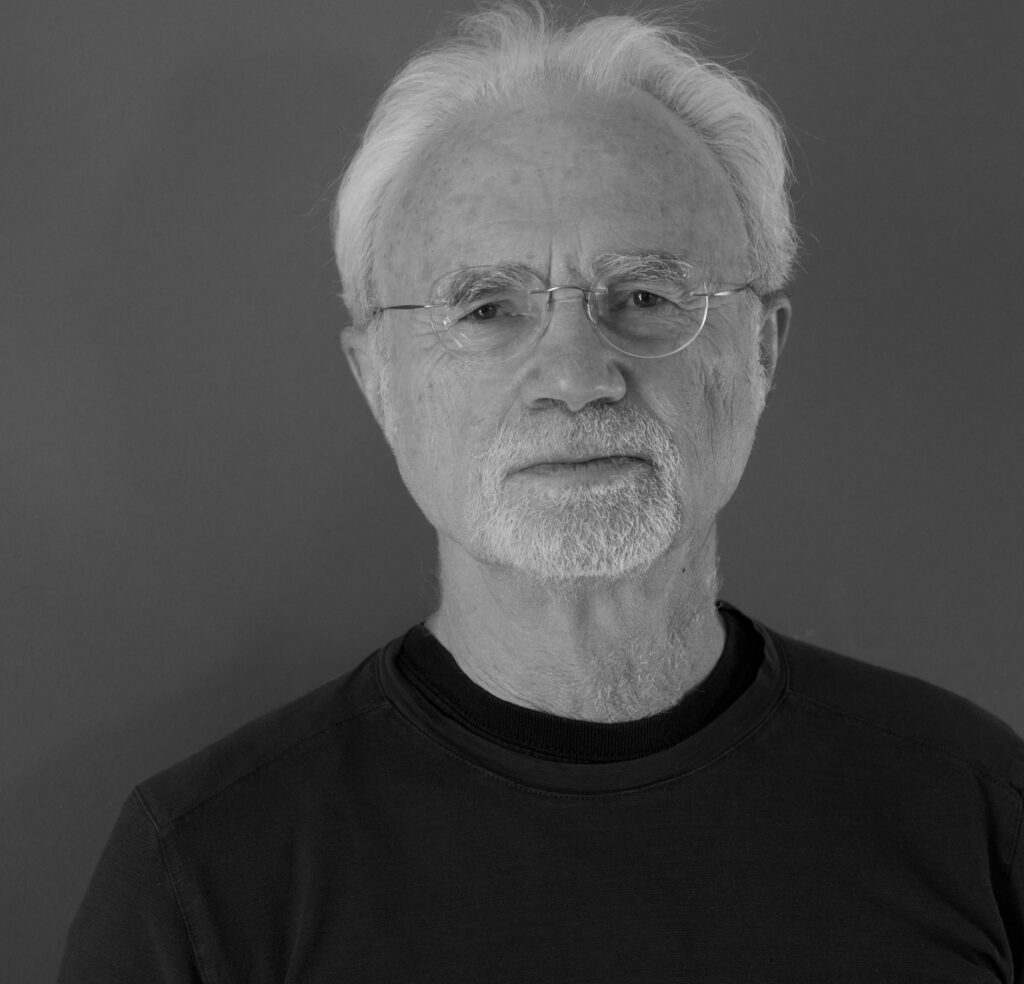

Geoffrey Hill was born in Worcestershire, England in 1932, where he grew up in constant view of the landscape that is Housman’s Shropshire. After earning a degree in English at Oxford, he taught for many years, first at the University of Leeds, then at Cambridge, before leaving for Boston University in 1988, where he remains on the faculty of the University Professors Program. Since 1998, he has also served as codirector of that university’s recently founded Editorial Institute. He makes his home in nearby Brookline, returning each summer to England, where he keeps a cottage in Lancashire.

Hill is the author of seven books of poems: For the Unfallen (1959), King Log (1968), Mercian Hymns (1971), Tenebrae (1978), The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Peguy(1983), Canaan (1997), and The Triumph of Love (1998). A new collection, Speech! Speech!, will be published this fall. He has also written two collections of essays, The Enemy’s Country: Words, Contexture, and Other Circumstances of Language (1984) and The Lords of Limit: Essays on Literature and Ideas (1991) and a version of Ibsen’s Brand, which was produced at the National Theatre in 1978. He is the recipient of awards that include the Hawthornden and Whitbread Prizes, as well as the Loines Award and a special citation for poetry from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters.

The interview was conducted at Hill’s home in Brookline over the course of two days in February of 1999, during and in the immediate wake of a blizzard that had hit Boston. During my drive up through the storm, I wondered what it would be like to interview my former teacher (I was a student of his at Boston University), and an initially rather formidable one at that? As it turns out, nothing would be as expected, starting with the house itself: from the outside, unassuming enough. To step into it, though, was to enter a number of seemingly disparate worlds: one part literal menagerie (two dogs, along with seven cats of varying degrees of forwardness); one part a kind of gallery—in the form of photographs on sideboards, walls, and mantles—of what is clearly central to Hill: family, ancestry, the need for the relationship between the living and the dead to be an active and ongoing one. Hill gave me a tour through them, now pointing out an infant cousin circa 1917, now his own parents, now his wife Alice Goodman, and their daughter Alberta, and now a friend riding her tractor through the Lancashire village streets.

When I first arrived, I was greeted by Alice (herself an intriguing mixture: the librettist for Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer, a translator of The Magic Flute for the Glyndebourne Opera, and a soon-to-be ordained Anglican priest). She led me into the living room where Hill arrived shortly, seating himself beside a life-sized dollhouse. We met in front of the fireplace, over whose mantle hung an amusing wedding gift: a copy of Hogarth’s The Distressed Poet. No way to explain it, exactly: I knew all would go well.

INTERVIEWER

The last time I saw you, you were admiring two very different types of art in the St. Louis Art Museum. One of them was Giovanni di Paulo’s St. Thomas Aquinas Confounding Averroes, and then there was the work of Anselm Kiefer. Ever since then I’ve been wondering whether you’d just discovered Kiefer that day, or not. And what was the attraction to two such very different types of art.

GEOFFREY HILL

I hadn’t heard of Kiefer until that day, and I was impressed by the physical presence, which was the same as a kind of spiritual aura, of his work. I bought the big book on Kiefer—lots of photographs—in the museum bookshop, and I have to say that I’m less gripped by them in this reduced form than I was with their actual presence. This may well be attributed to the judgment of the artist. There’s no reason why a work should accommodate itself to the kind of reproduction and reduction that our methods of communication and circulation require.

INTERVIEWER

And the di Paulo?

HILL

I was delighted by the difference between the little painting as the synopsis described it and what seemed to be the actual situation depicted. If I remember rightly, the synopsis said that St. Thomas is refuting Averroës, and that Averroës is writhing in pain and distress on the floor. Well, to me, he looked very peacefully asleep.

INTERVIEWER

I know you once found Averroës sympathetic, and then changed your mind—the notion of a single ruling intellect . . .

HILL

From which we emerge at birth, and into which we all become reabsorbed.

INTERVIEWER

Yes. And which also manages to absolve us in some way.

HILL

From our original sin, yes. And individual culpability. Yes, that was immediately attractive. Then as I thought more about it, it seemed scary as much as attractive.

INTERVIEWER

What comes up often in reviews of your work is the idea of an overly intellectual bent; in recent reviews of The Triumph of Love, often the word difficult comes up. People mention that it’s worth going through or it isn’t worth going through.

HILL

Like a Victorian wedding night, yes. Let’s take difficulty first. We are difficult. Human beings are difficult. We’re difficult to ourselves, we’re difficult to each other. And we are mysteries to ourselves, we are mysteries to each other. One encounters in any ordinary day far more real difficulty than one confronts in the most “intellectual” piece of work. Why is it believed that poetry, prose, painting, music should be less than we are? Why does music, why does poetry have to address us in simplified terms, when if such simplification were applied to a description of our own inner selves we would find it demeaning? I think art has a right—not an obligation—to be difficult if it wishes. And, since people generally go on from this to talk about elitism versus democracy, I would add that genuinely difficult art is truly democratic. And that tyranny requires simplification. This thought does not originate with me, it’s been far better expressed by others. I think immediately of the German classicist and Kierkegaardian scholar Theodor Haecker, who went into what was called “inner exile” in the Nazi period, and kept a very fine notebook throughout that period, which miraculously survived, though his house was destroyed by Allied bombing. Haecker argues, with specific reference to the Nazis, that one of the things the tyrant most cunningly engineers is the gross oversimplification of language, because propaganda requires that the minds of the collective respond primitively to slogans of incitement. And any complexity of language, any ambiguity, any ambivalence implies intelligence. Maybe an intelligence under threat, maybe an intelligence that is afraid of consequences, but nonetheless an intelligence working in qualifications and revelations . . . resisting, therefore, tyrannical simplification.

So much for difficulty. Now let’s take the other aspect—overintellectuality. I have said, almost to the point of boring myself and others, that I am as a poet simple, sensuous, and passionate. I’m quoting words of Milton, which were rediscovered and developed by Coleridge. Now, of course, in naming Milton and Coleridge, we were naming two interested parties, poets, thinkers, polemicists who are equally strong on sense and intellect. I would say confidently of Milton, slightly less confidently of Coleridge, that they recreate the sensuous intellect. The idea that the intellect is somehow alien to sensuousness, or vice versa, is one that I have never been able to connect with. I can accept that it is a prevalent belief, but it seems to me, nonetheless, a false notion. Ezra Pound defines logopaeia as “the dance of the intellect among words.” But elsewhere he changes intellect to intelligence. Logopaeia is the dance of the intelligence among words. I prefer intelligence to intellect here. I think we’re dealing with a phantom, or as Blake would say, a specter. The intellect—as the word is used generally—is a kind of specter, a false imagination, and it binds the majority with exactly the kind of mind-forged manacles that Blake so eloquently described. The intelligence is, I think, much more true, a true relation, a true accounting of what this elusive quality is. I think intelligence has a kind of range of sense and allows us to contemplate the coexistence of the conceptual aspect of thought and the emotional aspect of thought as ideally wedded, troth-plight, and the circumstances in which this troth-plight can be effected are to be found in the medium of language itself. I could speak about the thing more autobiographically; it’s the emphasis where one is most likely to be questioned, n’est-ce pas?

INTERVIEWER

Well, yes—go ahead.

HILL

Where my own poetry is concerned, I am to some extent an autodidact. And people say, Well, how can you possibly call yourself an autodidact? You went to Oxford, didn’t you? The syllabus I took for my B.A. in English at Oxford finished at 1832. It began with Anglo-Saxon—or Old English—moved through Middle English and finished with the second Reform Bill. Virtually all that has gone into my poetry, with the arguable exception of Mercian Hymns, has been the product of my own further reading and the kind of process of self-education, of fraternal and sororal education that one gets from one’s contemporaries: a decent enough form of education. The idea that you have here a scholar with superb, unarguable credentials, who as a kind of hobby enjoys turning his scholarship into rhyme and meter, is again I think totally alien to my own understanding of how the thing is done. All I can say is that it isn’t like that.

I’ll go further and say that I think men and women who write poetry or write music or paint are finally responsible for what they do. They are entitled to praise for any success they achieve and they should not complain of just criticism. I do stress that, just criticism. I do not think that poems and paintings and string quartets are created by currents of history. At the same time I think these individual men and women who are ultimately solely responsible for what they write and what they do as artists are very powerfully affected by contingent circumstance.