Issue 190, Fall 2009

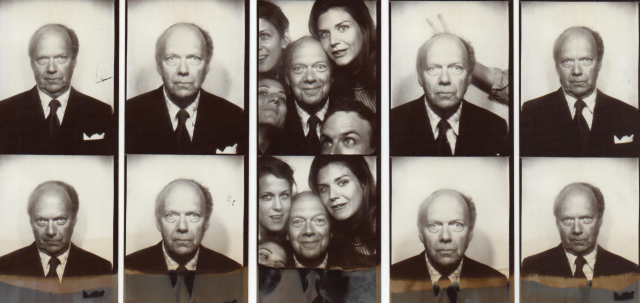

Frederick Seidel with friends, 2005.

Frederick Seidel with friends, 2005.

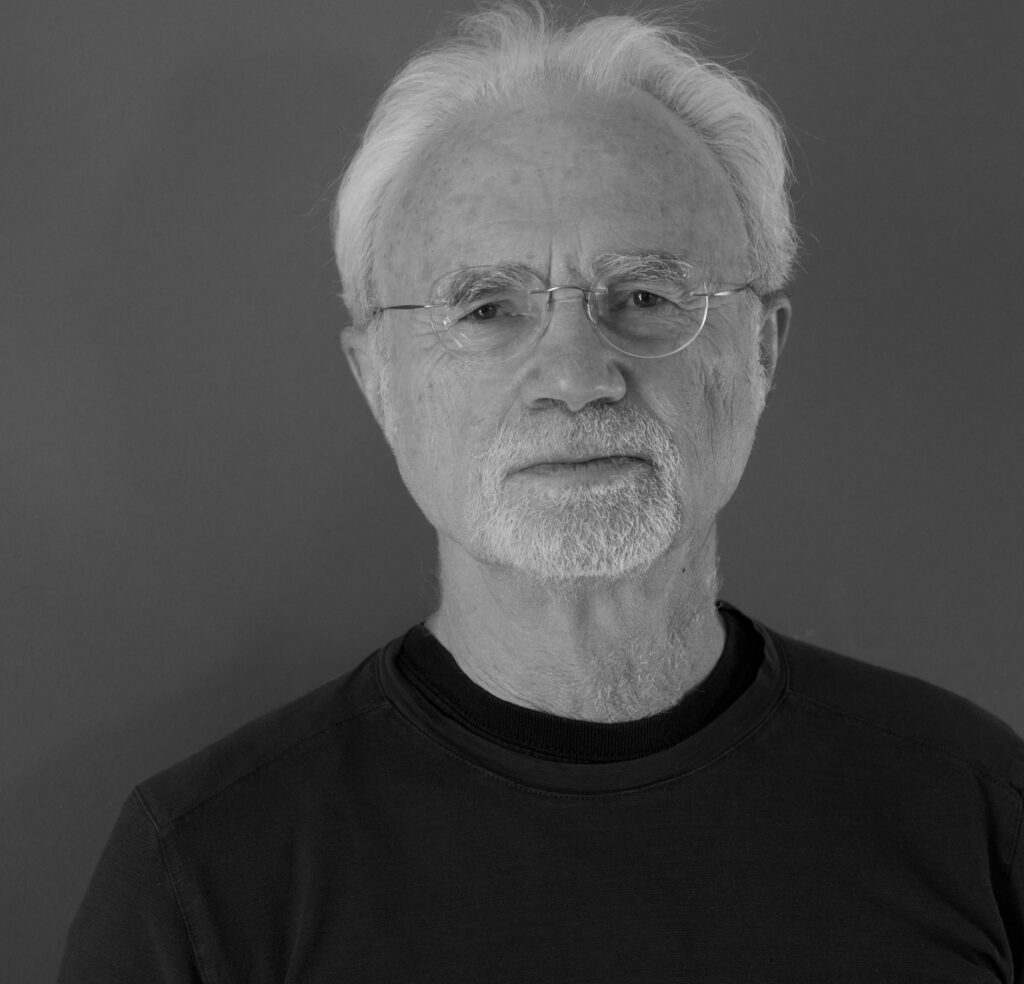

Frederick Seidel lives, as he has for several decades, in a rambling, light-filled apartment on New York’s Upper West Side. The place is comfortable and inviting, with paintings by friends on the walls and bibelots atop companionable, lived-with antique furniture. In the hallway is a life-size portrait by Alfred Eisenstaedt of the poet’s fellow St. Louisan T. S. Eliot, alongside another, of the Russian poet Osip Mandelstam. In contrast with the warm, stately order of the public rooms, the poet’s study at the end of the hall is a book-filled place of turbulent busyness, with an eagle’s-nest view down Broadway.

Seidel, who is seventy-three, speaks precisely, with what used to be called a Harvard accent. What can seem like hauteur gives way, on further acquaintance, to a genial sunniness; the poet’s conversation is often punctuated by peals of affectionate (or derisive) laughter. Seidel spends “gallons of time,” as he puts it, working at home. He is a dog lover, a motorcycle rider, an enthusiast of music and the movies—a solitary given to intimate sociability, an aficionado of the telephonic friendship.

Seidel’s reserve has involved an absolute refusal to participate in the public life of poetry. He has never given a reading and, as this writer, who is also his publisher, can ruefully attest, he doesn’t lift a finger to make himself known. Nevertheless, his work has slowly gathered a remarkably intelligent body of critical recognition along with a growing following among younger readers, and there is now a broad consensus that this reclusive, proud writer of willfully “disagreeable” poems is one of the great living practitioners of his art.

The poet’s work has won notoriety for a stance of épater-le-bourgeois knowingness that asserts with a cool rhetorical elegance that Seidel is on speaking terms with the haut monde (which is true enough), and that at the same time he essentially belongs to a society of one. It is the classic antisocial pose of the dandy, ennobled by Baudelaire but notably absent from most of American poetry. Some readers have failed to see beyond the stylistic carapace into the passionate heart—fearful, courageous, and tender—that it conceals and protects. As Benjamin Kunkel observed in Harper’s Magazine: “the excellent table manners combined with a savage display of appetite: this is what everyone notices in Seidel. Yet he wouldn’t be so special or powerful a poet of what’s cruel, corrupt, and horrifying had he not also lately shown himself to be a great poet of innocence.”

The interview took place in the Seidel apartment over a number of sessions in the winter of 2009, with additional conversations held later on with Lorin Stein, the poet’s editor at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. On a typical day, Seidel was wearing gray wide-wale corduroys, a black knit shirt, and very shiny black patent-leather sneakers.

INTERVIEWER

When did you know you wanted to be a poet?

FREDERICK SEIDEL

In 1949, when I was thirteen, in the library of the Saint Louis Country Day School. I should have been doing my homework or reading a book, but instead I was reading Time magazine. I found an article about Ezra Pound’s Pisan Cantos winning the Bollingen Prize and the great ruckus that followed. The article quoted the “What thou lovest well remains” lyric. In reading that lyric I had a moment that’s stayed with me for a lifetime. Four years later, astonishingly, I was with Pound, in Washington, at St. Elizabeths Hospital, where he had been committed to spare him from having to stand trial for treason.

INTERVIEWER

How did you manage that?

SEIDEL

I left St. Louis for Harvard—and for good—in 1953. In the fall of my freshman year I sent Pound a poem and a note that said, If it’s worth your while, it’s certainly worth mine. Meaning, I’d like to visit you.

No reply, until one day there arrived at Wigglesworth Hall an airmail special-delivery postcard with an indecipherable scrawl, front and back. The post office had managed to make out my name, so it got to me. I finally figured out that it said on the back, “Call Overholser.” It took me a while to realize that “Overholser” must be the name of the man who ran the hospital. I called, got permission, and boarded a Greyhound bus for Washington just before Thanksgiving, intending to stay for the weekend. I ended up staying for a week. On my arrival I presented Pound with a set of proposed corrections to his translation of Confucius, The Unwobbling Pivot. I’d been studying Chinese on my own. Need I say I didn’t know any Chinese?

INTERVIEWER

What sorts of changes were you contemplating?

SEIDEL

Clarifications. Making the language simpler.

INTERVIEWER

And what was his reaction?

SEIDEL

He was appalled, clearly. He didn’t say anything. Took the page from me. But at the end of the week, as I was leaving, he handed me a piece of paper with some of the corrections that I’d proposed for me to pass on to Professor Achilles Fang—superb name—of the Yenching Institute at Harvard, Pound’s Chinese-language man.

While I was at Saint Elizabeths, I saw him every day. John Kasper, a notorious neo-Nazi, had been visiting him every day as well. At the end of my first visit I told Pound that I wouldn’t come again if Kasper was going to be there, and after that Kasper never came. I got Pound to recite poems by Arnaut Daniel and Guido Cavalcanti and Guido Guinizzelli. It was wonderful to see him tilt his head back and orate the poems in this very old-timey way. We got on very well.

INTERVIEWER

Did you ever see him again?

SEIDEL

I didn’t. He sent me back to Harvard with a note for Archibald MacLeish. The note was on a piece of paper that was folded over once, and so of course it fell open. On the note it said, “Wake up, Archie!” Pound was angry that the various efforts to get him released from St. Elizabeths had gotten nowhere. When I handed the note to MacLeish, he was not pleased.

It was Pound’s idea that it was up to me, personally, to save Harvard. Once he wrote to me saying, “Only you can save Harvard from that kikesucking Pusey,” referring to Nathan Pusey, who had become president of the university the fall I arrived.

INTERVIEWER

Do you still have those letters?

SEIDEL

Alas, I don’t. I’m very bad at saving things.

INTERVIEWER

You took a leave of absence from Harvard to go to Europe, which wasn’t easy to get permission to do in those days, was it?

SEIDEL

MacLeish arranged it for me. I went to Paris first, where I took a vow of silence, which I pretty much kept to for three months. I suppose I thought it might teach me something. Meanwhile, I read all of Freud in English, and walked the streets, and attended classes at the Sorbonne, which I did not like at all. I crossed the Channel to have a look at Oxford and Cambridge, which seemed to me even sillier than Harvard. So, a bit to my own surprise, I returned to Harvard.