Issue 10, Fall 1955

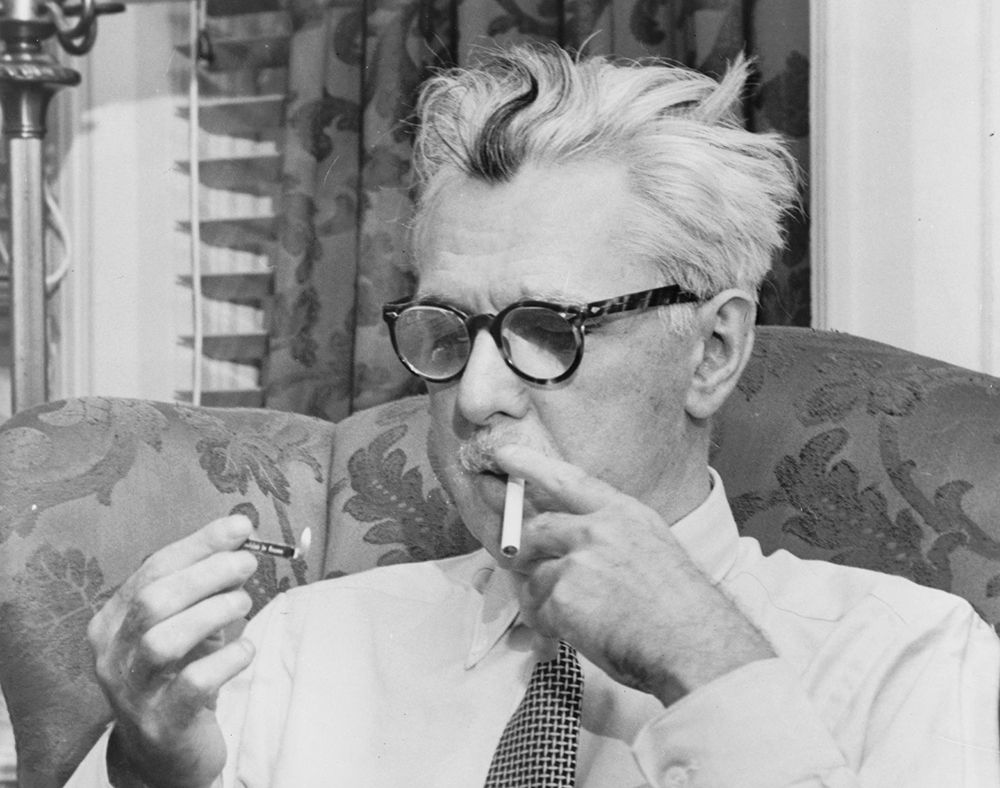

Photo by Fred Palumbo, Library of Congress

The Hôtel Continental, just down from the Place Vendôme on the Rue Castiglione. It is from here that Janet Flanner (Genêt) sends her Paris letter to The New Yorker, and it is here that the Thurbers usually stay while in Paris. “We like it because the service is first-rate without being snobbish.”

Thurber was standing to greet us in a small salon whose cold European formality had been somewhat softened and warmed by well-placed vases of flowers, by stacks and portable shelves of American novels in bright dust jackets, and by pads of yellow paper and bouquets of yellow pencils on the desk. Thurber impresses one immediately by his physical size. After years of delighting in the shy, trapped little man in the Thurber cartoons and the confused and bewildered man who has fumbled in and out of some of the funniest books written in this century, we, perhaps like many readers, were expecting to find the frightened little man in person. Not at all. Thurber, by his firm handgrip and confident voice, and by the way he lowered himself into his chair, gave the impression of outward calmness and assurance. Though his eyesight has almost failed him, it is not a disability which one is aware of for more than the opening minute, and if Thurber seems to be the most nervous person in the room, it is because he has learned to put his visitors so completely at ease.

He talks in a surprisingly boyish voice, which is flat with the accents of the Midwest where he was raised and, though slow in tempo, never dull. He is not an easy man to pin down with questions. He prefers to sidestep them and, rather than instructing, he entertains with a vivid series of anecdotes and reminiscences.

Opening the interview with a long history of the bloodhound, Thurber was only with some difficulty persuaded to shift to a discussion of his craft. Here again his manner was typical—the anecdotes, the reminiscences punctuated with direct quotes and factual data. His powers of memory are astounding. In quoting anyone—perhaps a conversation of a dozen years before—Thurber pauses slightly, his voice changes in tone, and you know what you’re hearing is exactly as it was said.

JAMES THURBER

Well, you know it’s a nuisance—to have memory like mine—as well as an advantage. It’s … well … like a whore’s top drawer. There’s so much else in there that’s junk—costume jewelry, unnecessary telephone numbers whose exchanges no longer exist. For instance, I can remember the birthday of anybody who’s ever told me his birthday. Dorothy Parker—August 22, Lewis Gannett—October 3, Andy White—July 9, Mrs. White—September 17. I can go on with about two hundred. So can my mother. She can tell you the birthday of the girl I was in love with in the third grade, in 1903. Offhand, just like that. I got my powers of memory from her. Sometimes it helps out in the most extraordinary way. You remember Robert M. Coates? Bob Coates? He is the author of The Eater of Darkness, which Ford Madox Ford called the first true Dadaist novel. Well, the week after Stephen Vincent Benét died—Coates and I had both known him—we were talking about Benét. Coates was trying to remember an argument he had had with Benét some fifteen years before. He couldn’t remember. I said, “I can.” Coates told me that was impossible since I hadn’t been there. “Well,” I said, “you happened to mention it in passing about twelve years ago. You were arguing about a play called Swords.” I was right, and Coates was able to take it up from there. But it’s strange to reach a position where your friends have to be supplied with their own memories. It’s bad enough dealing with your own.

INTERVIEWER

Still, it must be a great advantage for the writer. I don’t suppose you have to take notes.

THURBER

No. I don’t have to do the sort of thing Fitzgerald did with The Last Tycoon—the voluminous, the tiny and meticulous notes, the long descriptions of character. I can keep all these things in my mind. I wouldn’t have to write down “three roses in a vase” or something, or a man’s middle name. Henry James dictated notes just the way that I write. His note-writing was part of the creative act, which is why his prefaces are so good. He dictated notes to see what it was they might come to.

INTERVIEWER

Then you don’t spend much time prefiguring your work?

THURBER

No. I don’t bother with charts and so forth. Elliott Nugent, on the other hand, is a careful constructor. When we were working on The Male Animal together, he was constantly concerned with plotting the play. He could plot the thing from back to front—what was going to happen here, what sort of situation would end the first-act curtain, and so forth. I can’t work that way. Nugent would say, “Well, Thurber, we’ve got our problem, we’ve got all these people in the living room. Now what are we going to do with them?” I’d say that I didn’t know and couldn’t tell him until I’d sat down at the typewriter and found out. I don’t believe the writer should know too much where he’s going. If he does, he runs into old man blueprint—old man propaganda.

INTERVIEWER

Is the act of writing easy for you?

THURBER

For me it’s mostly a question of rewriting. It’s part of a constant attempt on my part to make the finished version smooth, to make it seem effortless. A story I’ve been working on—“The Train on Track Six,” it’s called—was rewritten fifteen complete times. There must have been close to 240,000 words in all the manuscripts put together, and I must have spent two thousand hours working at it. Yet the finished version can’t be more than twenty-thousand words.

INTERVIEWER

Then it’s rare that your work comes out right the first time?

THURBER

Well, my wife took a look at the first version of something I was doing not long ago and said, “Goddamn it, Thurber, that’s high-school stuff.” I have to tell her to wait until the seventh draft, it’ll work out all right. I don’t know why that should be so, that the first or second draft of everything I write reads as if it was turned out by a charwoman. I’ve only written one piece quickly. I wrote a thing called “File and Forget” in one afternoon—but only because it was a series of letters just as one would ordinarily dictate. And I’d have to admit that the last letter of the series, after doing all the others that one afternoon, took me a week. It was the end of the piece and I had to fuss over it.

INTERVIEWER

Does the fact that you’re dealing with humor slow down the production?

THURBER

It’s possible. With humor you have to look out for traps. You’re likely to be very gleeful with what you’ve first put down, and you think it’s fine, very funny. One reason you go over and over it is to make the piece sound less as if you were having a lot of fun with it yourself. You try to play it down. In fact, if there’s such a thing as a New Yorker style, that would be it—playing it down.

INTERVIEWER

Do you envy those who write at high speed, as against your method of constant revision?

THURBER

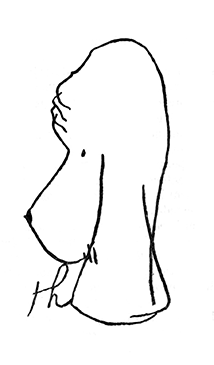

Oh, no, I don’t, though I do admire their luck. Hervey Allen, you know, the author of the big best-seller Anthony Adverse, seriously told a friend of mine who was working on a biographical piece on Allen that he could close his eyes, lie down on a bed, and hear the voices of his ancestors. Furthermore there was some sort of angel-like creature that danced along his pen while he was writing. He wasn’t balmy by any means. He just felt he was in communication with some sort of metaphysical recorder. So you see the novelists have all the luck. I never knew a humorist who got any help from his ancestors. Still, the act of writing is either something the writer dreads or actually likes, and I actually like it. Even rewriting’s fun. You’re getting somewhere, whether it seems to move or not. I remember Elliot Paul and I used to argue about rewriting back in 1925 when we both worked for the Chicago Tribune in Paris. It was his conviction you should leave the story as it came out of the typewriter, no changes. Naturally, he worked fast. Three novels he could turn out, each written in three weeks’ time. I remember once he came into the office and said that a sixty-thousand-word manuscript had been stolen. No carbons existed, no notes. We were all horrified. But it didn’t bother him at all. He’d just get back to the typewriter and bat away again. But for me—writing as fast as that would seem too facile. Like my drawings, which I do very quickly, sometimes so quickly that the result is an accident, something I hadn’t intended at all. People in the arts I’ve run into in France are constantly indignant when I say I’m a writer and not an artist. They tell me I mustn’t run down my drawings. I try to explain that I do them for relaxation, and that I do them too fast for them to be called art.