Issue 130, Spring 1994

At the center of Kesey’s work are what he calls “little warriors” battling large forces. Over the years, some critics have praised his work for its maverick power and themes of defiance; others have questioned his wild and paranoid vision. He has been dubbed a renegade prophet, a subversive technophile, a spiritual junkie—characterizations that Kesey does little to discourage.

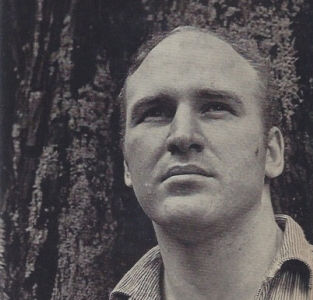

He lives in a spacious barn that was built in the thirties from a Sears Roebuck catalog. It is decorated in bright Day-Glo colors. The stairs ascending to his loft-study are covered in streaks of neon green and pink, recalling the psychedelic designs made famous by Kesey’s bus, Furthur. Inspired by these visual remnants of the sixties, Kesey works late into the night, observed, as he points out, by a parliament of owls.

This interview was conducted during several visits with Kesey at his Oregon farm in 1992 and 1993.

INTERVIEWER

Your only formal studies in fiction were as a fellow in Wallace Stegner’s writing program at Stanford. What did you learn from Stegner and also from Malcolm Cowley?

KEN KESEY

The greatest thing Cowley taught me was to respect other writers’ feelings. If writing is going to have any effect on people morally, it ought to affect the writer morally. It is important to support everyone who tries to write because their victories are your victories. So I have never really felt that bitter cattiness writers feel toward their peers.

INTERVIEWER

Yet you had a difficult relationship with Stegner. What were the differences between you?

KESEY

Shortly after Cuckoo’s Nest came out, I did an interview with Gordon Lish for a magazine called Genesis West. I don’t remember exactly what I said about Stegner, but it made him angry. When I heard he was angry I tried to see him, but his secretary wouldn’t let me in. We never spoke again after that. Wally never did like me. At one point, I read that he had said he found me to be ineducable. I had to stew for a long time over what Stegner didn’t like about me and my friends. We were part of an exceptional group, there’s no doubt about it. There was Bob Stone, Gurney Norman, Wendell Berry, Ken Babbs, and Larry McMurtry. All of us who were part of that group are still very much in contact; we all support each other’s work. Stegner was the great force that brought us all together. He put together a program that ruled literature in California and, in some ways, the rest of the nation for a long time. Stegner had traveled across the Great Plains and reached the Pacific but, as far as he was concerned, that was far enough. Some of us didn’t believe that it was far enough and when we went farther than that, he took issue with it, especially when it was not happening in the usual literary bailiwicks that he was accustomed to. I took LSD and he stayed with Jack Daniel’s; the line between us was drawn. That was, as far as he was concerned, the edge of the continent, and he thought you were supposed to stop there. I was younger than he was and I didn’t see any reason to stop, so I kept moving forward, as did many of my friends. Ever since then, I have felt impelled into the future by Wally, by his dislike of what I was doing, of what we were doing. That was the kiss of approval in some way. I liked him and I actually think that he liked me. It was just that we were on different sides of the fence. When the Pranksters got together and headed off on a bus to deal with the future of our synapses, we knew that Wally didn’t like what we were doing and that was good enough for us. A few years ago, I taught a course at the University of Oregon. I began to appreciate Wally much more after I had been a teacher. Every writer I know teaches—at some point, even if you don’t need the money, you have to teach what you were taught, especially if you were taught by a great coach.

INTERVIEWER

Did your experience at Stanford drive you to an anti-intellectual stance?

KESEY

The reason you read great authors—Thomas Paine, Jefferson, Thoreau, Emerson—is not because you really want to teach them, though that’s one of the things you find yourself doing because you know it’s important that they be taught. You study literature because you’re a scholar of what’s fair. It’s just a way of learning how to be what we want to be. We go to concerts to hear a piece by Bach not because we want to be intellectuals or scholars or students of Bach, but because the music is going to help us keep our moral compass needle clean.

INTERVIEWER

What connection is there between Ken Kesey the magician-prankster and Ken Kesey the writer?

KESEY

The common denominator is the joker. It’s the symbol of the prankster. Tarot scholars say that if it weren’t for the fool, the rest of the cards would not exist. The rest of the cards exist for the benefit of the fool. The fool in tarot is this naive innocent spirit with a rucksack over his shoulder like Kerouac, his eyes up into the sky like Yeats, and his dog biting his rump as he steps over the cliff. We found one once at a big military march in Santa Cruz. Thousands of soldiers marching by. All it took was one fool on the street corner pointing and laughing, and the soldiers began to be uncomfortable, self-conscious. That fool of Shakespeare’s, the actor Robert Armin, became so popular that finally Shakespeare wrote him out of Henry IV. In a book called A Nest of Ninnies, Armin wrote about the difference between a fool artificial and a fool natural. And the way Armin defines the two is important; the character Jack Oates is a true fool natural. He never stops being a fool to save himself; he never tries to do anything but anger his master, Sir William. A fool artificial is always trying to please; he’s a lackey. Ronald McDonald is a fool artificial. Hunter Thompson is a fool natural. So was the Little Tramp. Neal Cassady was a fool natural, the best one we knew.

INTERVIEWER

Neal Cassady was a muse to the Beats and became one to you as you started writing. When did you first encounter him?

KESEY

It was 1960. He had just finished the two years he served in the pen. He showed up at my place on Perry Lane when I was at Stanford. He arrived in a Jeep with a blown transmission, and before I was able to get outside and see what was going on, Cassady had already stripped the transmission down into big pieces. He was talking a mile a minute and there was a crowd of people around him. He never explained why he was there, then or later. He always thought of these events as though he was being dealt cards on a table by hands greater than ours. But that was one of my earliest impressions of him as I watched him running around, this frenetic, crazed character speaking in a monologue that sounded like Finnegans Wake played fast forward. He had just started to get involved in the drug experiments at the hospital in Menlo Park, as I had. I thought, Oh, my God, it could lead to this. I realized then that there was a choice. Cassady had gone down one road. I thought to myself, Are you going to go down that road with Burroughs, Ginsberg, and Kerouac—at that time still unproven crazies—or are you going to take the safer road that leads to John Updike. Cassady was a hero to all of us who followed the wild road, the hero who moved us all.

INTERVIEWER

Were there literary influences as well?

KESEY

Many of us had read Ginsberg’s “Howl,” Kerouac’s On the Road, Kenneth Rexroth’s work, Ferlinghetti’s. I knew their work when I was a student at the University of Oregon. I had a tape of Ferlinghetti saying, “I’m sitting now outside of my pool hall watching the hipsters come by in their curious shoes.” I wanted to go down to the North Beach area and see Mike’s Pool Hall. That’s where I met Ken Babbs and Bob Kaufman, a great poet and a casualty of exploration of the synapses.

INTERVIEWER

Do you think the drug experimentation produced mostly casualties? Do you think Cassady was one?

KESEY

I think most artists who, as the saying goes now, “push the envelope” wind up as casualties. If you think about the history of writers and artists, the best often don’t end up with pleasant, comfortable lives; sometimes they go over the edge and lose it. I’ve been close to enough casualties to learn how to avoid that pitfall. Some critics like to argue that some of the Beats had a death wish. Cassady certainly didn’t have a death wish. He had a more-than-life wish, an eternity wish. He was trying to recapture, as Burroughs says, the realities he had lost. He was storming the reality studio and trying to take the projector from the controllers who had been running it. When that happens you are bound to have some casualties.