At the orangutan dome the grandfather purchases a plastic cup in the shape of an orangutan head. He offers his grandson a sip. Then he slips behind a tree with the cup and afterwards the boy isn’t allowed to drink from it. The boy begs for his own.

Eight dollars for soda in a plastic head, his mother thinks. The flesh-and-blood orangutan is dignified and bored. It sighs and its body deflates. The family turns toward a glass case labeled FENNEC FOX. “Look,” the grandfather says. “Weasels.”

The foxes are tiny, Chihuahuas with gold fur and satellite-dish ears. “Elephant weasels can hear things happening in space,” the grandfather tells the boy. “They can hear when your tummy rumbles and they think how much they’d like a little boy to snack on.” The boy clutches his grandfather’s hand. He believes nearly everything anyone tells him. He has large, serious eyes and a look of constant apprehension that make it easy for his mother to forget his growing size, that he is too old now for the collapsible stroller she has brought in case he becomes tired. His legs dangle whenever she straps him in with the juice boxes and snacks.

“You know what their favorite foods are?” the grandfather asks. Everyone standing at the enclosure knows, because the label lists them: plants, small rodents, lizards, and insects. “Elephant weasels love roast beef,” the grandfather says. “And key lime pie. And kid stew.” He picks up the boy to give him a better view. The people at the enclosure decide they do not care enough to bother saying anything. Let the foxes be weasels. What does it hurt?

The mother does not share their indifference. She grinds her teeth when her father speaks. Her whole life he has been telling these stories, and there was once a time she believed them. As a child she gave show-and-tell presentations on birds that turned out not to exist, on fictive countries whose names were sexual innuendo she was too young to understand. She was marked down, taken aside by concerned teachers. She still winces at those old humiliations, her own credulity. She has promised herself that her son will grow up on firmer footing.

The grandfather has one hand around the boy and the other around his drink. He gestures with the cup and the orangutan head smacks the glass. The foxes prick their ears toward the sound. Someday, the mother thinks, her father will break her son’s gullible little heart.

“Let’s see something bigger,” he says. “This zoo got any rhinos?”

The mother is a patent lawyer. Her father is in town for the week visiting, and she is using a vacation day rather than leave him alone with her son. She is supposed to be preparing an infringement suit related to proprietary athletic surfacing, patented types of artificial turf and running track. Her husband is a dermatologist, and they will always have enough money, the lawyer and the doctor. On the way to the rhinos the family passes the capybara habitat. “What do they eat?” the boy asks.

“Fritos,” the grandfather says. “But these might do.” He flings a handful of chips over the fence, a new kind of Doritos that were for sale in the Orangutan Dome, mystery-flavored and slightly green. The chips land in the moat and the capybaras turn their heads to watch. The chips start to dissolve and the capybaras disappear into the reeds. The boy is sad to see them go.

The boy’s favorite television shows are all on Animal Planet and he sobs piteously when anything dies. His favorite stories are all fairy tales. He likes Dora the Explorer and dislikes Bob the Builder. He ties ribbons around the necks of his stuffed animals. It has occurred to his parents that the boy might turn out to be gay and that these are the early signs. He is who he is, they tell themselves, whoever that turns out to be. The boy’s grandfather finds this repellent.

After the capybaras comes SafariLand. “Giraffe,” the son says, when his grandfather points out the neck monsters. His mother wants to cheer.

“Sure, I recognize them now. We rode them, in the war,” the grandfather explains. In fact, he has not been in any war. He enlisted after Korea and spent two years in Fort Greely, Alaska. He tells war stories like it’s expected of him, like he doesn’t know any other way to be an old man, a grandfather. “Giraffes sure can move. Gallop like motherfuckers.”

The boy was too excited last night to sleep, and his mother read to him from The Big Book of Amazing Animal Behavior to calm him. There is an illustration of an antelope cleaning its nose with its tongue that fascinates and shocks the boy. Sometimes at night he thinks of this picture, the animal with its tongue in its nose. This zoo has several antelopes, but none of them are picking their noses. The boy is disappointed. There are oryx, gazelles, Cape hunting dogs, a cheetah. It is midday, and most of the animals are sleeping.

The boy’s book explains that elephants are social animals, that the individuals in a family love each other very much. Here at the zoo, he notices that the elephants are caged separately, snorting and kicking at one another. The boy asks his mother why.

A sign explains that the elephants are mentally ill. They are seeing an elephant therapist and taking antianxiety medication, but there is some doubt as to whether they will ever be cured. The mother does not want to explain this to her son. She thinks that lawyers are supposed to be better at prevarication, at thinking on their feet, but that has never been the kind of lawyering she was good at. She is good at proprietary athletic surfaces.

It is difficult, however, to stay very interested in athletic surfaces. This is what makes her grateful for the mad scientist who keeps soliciting her counsel in regard to a “temporal transportation device” he invented—he’s something different, at least. I have discovered how to circumvent the problems of the Blinovitch Limitation Effect and the Novikov Self-Consistency Principle, he wrote in his first letter, sent registered mail. You’re the only one I can trust. This technology has to stay in the right hands.

The lawyer has no idea why her hands were the right ones, the trusted ones, but there she was, holding the blueprints.

“A time machine,” the secretaries said matter-of-factly as they watched her unroll the diagrams on the large table in the conference room. “That’s a new one.” The secretaries take his packages directly to her office now, lurking until she opens them. The first was a silver gravy boat: I successfully impersonated a member of King Edward VII’s household staff and served him gravy in 1901. Regrettably, I had to abscond with the item to have proof. Thus the price of progress. I hope you do not think me a common criminal. She has called the other patent law firms in the city, but no one else has been receiving anything stranger than usual. “Someone sent us schematics for wings,” another lawyer offered. “The Daedalus 3000. Think it’s the same guy?”

In the mother’s silence, the grandfather steps in. He can understand what the elephants are saying, he says. He gets elephants, like he gets elephant weasels. He comprehends their growls of discomfort and anxiety. “They had a fight this morning,” the grandfather says. “Over their toys. They’re sulky now, but they’ll come around.” The only toys the boy sees are tangles of knotted rope, a funnel of food on a post, a pile of hay, and some rocks. The boy thinks of his dentist’s waiting room with its few Highlights magazines and many toothless children. They waggle their loose fangs at the boy, whose own teeth are still small and white and planted firmly in his jaw, then they ruin the hidden pictures by coloring in what’s hidden. The grandfather’s explanation makes perfect sense to the boy, and he is curious about what else his grandfather knows. The boy points expectantly at a gazelle.

“Most of the time animals don’t say much worthwhile,” the grandfather explains. “Anteaters just say, ‘Ants! Ants! Ants!’ And owls say, ‘Fly! Hunt! Fly!’ And mice say, ‘I’m small! I’m frightened! Oh no! An owl! I’m fright—slurp.’”

“Ants ants ants ants ants ants ants,” the boy whispers on the way to the next enclosure, making a long nose with his arm. He waves the anteater snout in front of him.

“You want to go back to the elephants?” his mother guesses.

The boy is disappointed in her. “Anteater,” he explains.

The mad scientist has started writing for your eyes only on his envelopes. “Be careful,” the secretaries say. “Could be anthrax.” In a padded envelope was a single bullet casing: I saw this shot fired in 1811 during the expulsion of the Xhosa tribe from the Zuurveld. He sent a pink skirt, writing, This may look like a typical flounced Crimplene skirt from the 1960s, but I in fact purchased this item in the year 2206, when mid-twentieth-century fashions enjoy a blessedly brief vogue. 2207 will be all about ponchos. She has found herself looking, really looking, over the blueprints. The machine isn’t familiar: not a DeLorean or Bill and Ted’s phonebooth or Doctor Who’s police box or any ships she recognizes from Star Trek or Star Wars or H. G. Wells. It is simply a smooth metal tube that does not seem, somehow, like something a crazy person would design. She has asked her husband if dermatology holds such surprises. He shrugged. “I didn’t know how many mole checks I’d do,” he said. “Everyone’s worried about skin cancer.”

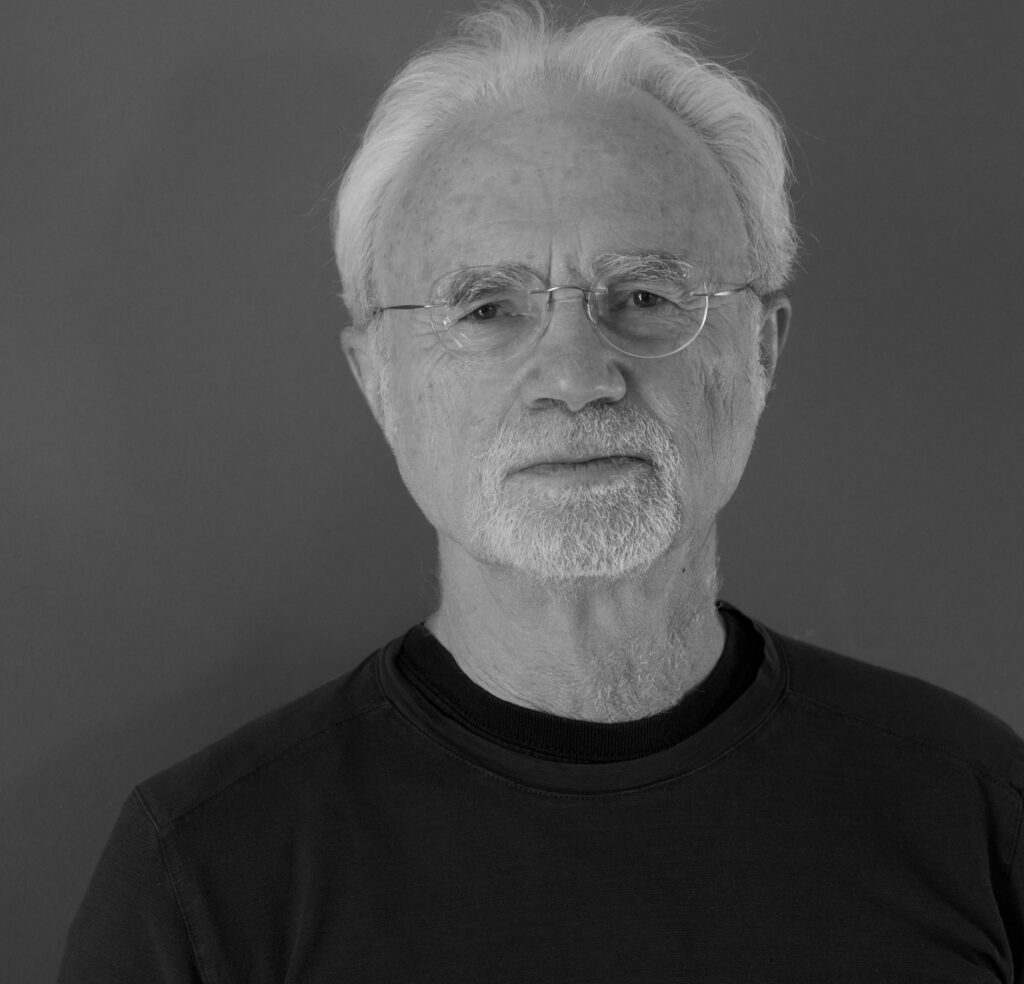

Her father has had a cancer on his cheekbone and one on the top of his left ear. The ear is scarred neatly over but the cheek cancer was recent, and there is still a square white bandage taped across the furrow the doctors dug. They offered to take a skin graft from his thigh to patch it, but he refused. As a landscaper he took satisfaction in his workingman’s tan and powerful shoulders. He retired several years ago, pain in his back, sore knees and elbows. Now the alcohol keeps him loose. He does not like the way his body feels when he is sober. He does not like the way the air touches his cheek when he changes his bandage, the way it brushes something private.

“Hey kid,” the grandfather says. “Do you know why lions eat raw meat?”

The boy shakes his head.

“Because they don’t know how to cook.”

The mother rolls her eyes; her son blinks.

“Why do birds fly south for the winter, Hornswoggle? Too far to walk.” When the grandfather isn’t calling the boy Tyke or Junior or Hey Kid, he calls him Hornswoggle. No one has any idea why. “What’s black-and-white and red all over? A zebra who didn’t look both ways. Which side of a bird has the most feathers? The outside.”