This piece was published as part of an April Fool's post in 2015, entitled "Introducing The Paris Review for Young Readers." It is a fictional interview, and intended purely as a parody. It is not intended to communicate any true or factual information, and is for entertainment purposes only.

From The Paris Review for Young Readers, Issue 1, Spring 2015

INTERVIEWER

Do you find you need a certain disposition to write for children?

CARLE

Yes and no. The party line is that one should write to children exactly as one would write to adults, and this is true, as far as it goes. But a child is an almost platonic reader. His imagination remains unbounded—his sense of jouissance, if you will, is very much intact. In addressing children, a writer must summon that same jouissance in himself.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have a method for that?

CARLE

Games help. Toys help. Music with a certain prelapsarian gaiety—Christmas music, especially—is invaluable.

INTERVIEWER

You listen to Christmas music when you write?

CARLE

I listen to whatever renews my childish appetites—whatever brings out my inner boy. And the results, you can see, are juvenile not just in their style and aesthetic but in their morality. This may sound high-minded, but they exist before adult ethics, and this is why children respond to them.

INTERVIEWER

Can you give an example?

CARLE

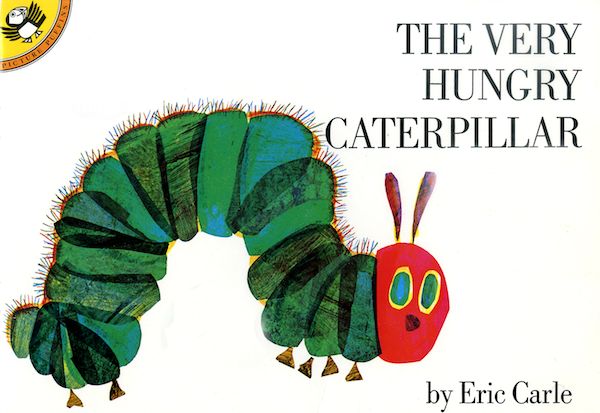

My publisher and I fought bitterly over the stomachache scene in The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The caterpillar, you’ll recall, feasts on cake, ice cream, salami, pie, cheese, sausage, and so on. After this banquet I intended for him to proceed immediately to his metamorphosis, but my publisher insisted that he suffer an episode of nausea first—that some punishment follow his supposed overeating. This disgusted me. It ran entirely contrary to the message of the book. The caterpillar is, after all, very hungry, as sometimes we all are. He has recognized an immense appetite within him and has indulged it, and the experience transforms him, betters him. Including the punitive stomachache ruined the effect. It compromised the book.

INTERVIEWER

Was your publisher worried about encouraging gluttony?

CARLE

Perhaps, but that’s of no concern to the child—nor should it be. I don’t recognize childhood obesity. No one should. I see children doing what they like, which is eating, and doing it without the shame or remorse later drilled into them by Judeo-Christian ethics. This is what I mean when I say juvenile morality: it’s a kind of a priori humanism. Children predate the law. That juvenile has become a pejorative is one of the saddest facts of our language.

INTERVIEWER

Have you considered publishing a corrected edition of The Very Hungry Caterpillar, then?

CARLE

No, but I’ve managed to subvert adult expectations—to write for my true audience—in other books. A lot of parents ask me about the end of Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?, where the last thing the children see is “a teacher looking at us. That’s what we see.” To adults, it seems abrupt, arbitrary. Really it’s anything but. After living in a world of blue horses and purple cats—a world of perfect play—the children are confronted, finally, with a vision of authority. The teacher stands for a tired mode of seeing. Under her reproachful gaze the children can’t go on in their ludic mode. The teacher is end of the world for them. To grown-ups this ending is a mystery. To children it’s stupefyingly obvious.