Issue 236, Spring 2021

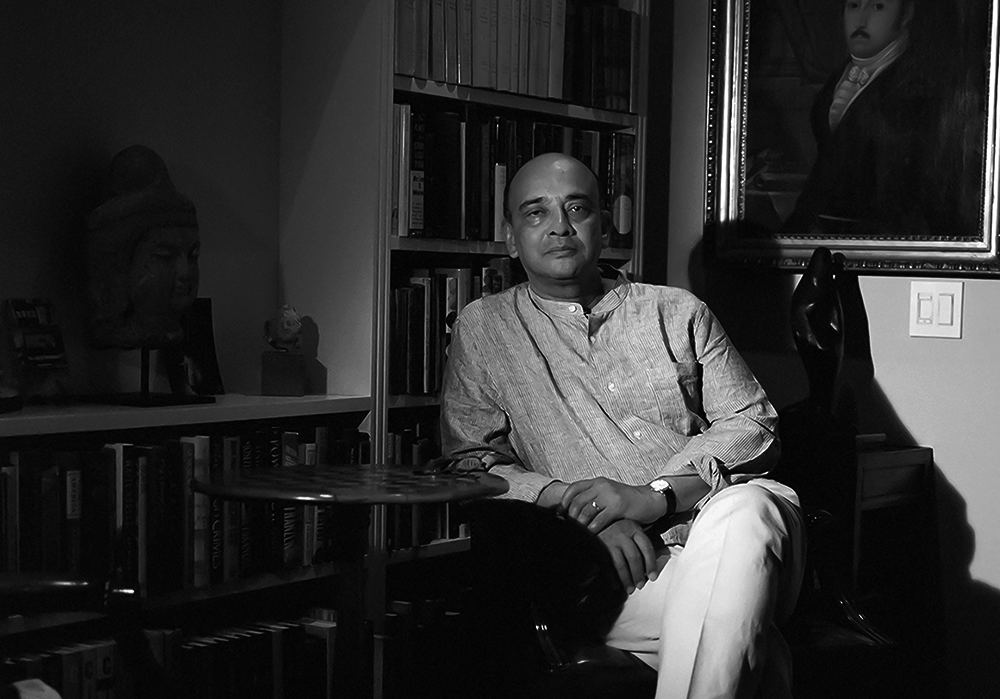

Appiah in New York, 2018. Photo by Yael Malka

Fifty years ago, at a harp recital in Gloucestershire, a retired British military officer with a clipped aristo accent came across a brown-skinned teenager. “I say, old chap, do you speak English?” the officer said.

As a story in Yale’s New Journal recounted, the young man—Kwame Anthony Akroma-Ampim Kusi Appiah—replied, “Why don’t you ask my grandmother?”

“Who, may I ask, is your grandmother?” the retired officer said.

“Lady Cripps.”

Lady Cripps was Isobel Cripps, the widow of Sir Stafford Cripps, a Christian socialist and Labour politician who had been chancellor of the exchequer and the Crown’s ambassador to the Soviet Union; he was known for his stalwart desire to relinquish Britain’s imperial possessions, from Calcutta to Accra. In 1953, the year of Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, Stafford and Isobel’s daughter Peggy married Joe Appiah, kinsman of Ashanti kings and a leader of the Ghanaian independence movement. (The marriage would help inspire the film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.) A year later, the Appiahs’ first child and only son was born.

When Anthony was growing up in Kumasi, the capital of the Ashanti region of Ghana, the Appiah household was a locus of political and literary conversation. Among the visitors were the historian and activist C. L. R. James, the Pan-Africanist George Padmore, and the novelist Richard Wright. Joe Appiah instilled in his son a sense of global citizenship and family honor. As Anthony once wrote, “I found myself remembering my father’s parting words, years ago, when I was a student leaving home for Cambridge—I would not see him again for six months or more. I kissed him in farewell, and, as I stood waiting by the bed for his final benediction, he peered at me over his newspaper, his glasses balanced on the tip of his nose, and pronounced: ‘Do not disgrace the family name.’ Then he returned to his reading.”

Appiah earned a double first degree at Clare College, Cambridge, and then a Ph.D. in philosophy, the first African at the university to do so. He is perhaps best known, among nonphilosophers, for his work on cosmopolitanism and the nature of identity in a globalized world, though his bibliography and his range are vast. He is the author of sixteen books (including three mystery novels, which he considers, in Graham Greene’s terms, the “entertainments”). Although his earliest works are best enjoyed by professional philosophers, his writing for decades has been sparklingly lucid; each book wrestles with problems immensely relevant to modern life: identity, race, sexuality, nationalism, liberalism, our capacity to live together on one planet. For instance, In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture (1992), in its nine essays, provides a memoir of his father, examines the varied fates of African nation-states in the postcolonial era, and criticizes the very idea of race as a human category. Everywhere in his work, Appiah urges readers to see the multiplicities of our identities, which both define our individuality and describe a commonality. There is never a trace of dogma or ill will. He is the teacher—patient and erudite—you always wished you had. And now you do.

Through these efforts Kwame Anthony Appiah has become one of the most celebrated thinkers of his generation; in 2012, President Obama awarded him the National Humanities Medal for “seeking eternal truths in the contemporary world.” He has held faculty positions at Yale, Cornell, Duke, Harvard, Princeton, and the University of Ghana, in Accra; he is now a professor of philosophy at New York University. Appiah also lectures all over the world and writes the Ethicist column in The New York Times Magazine. He and his husband, Henry Finder, the editorial director of The New Yorker, live in an apartment in Manhattan and an eighteenth-century farmhouse in Princeton, where sheep can be found gamboling near the barn.

Appiah’s is a protean, rigorous, generous, and elegant mind; he is a multilingual scholar whose interests range from probabilistic semantics to political theory and, in his Times column, such problems as a troublesome in-law or a violent house pet. As one might expect from someone whose ancestors include leading figures at the court of Ashanti back to the eighteenth century and left-leaning aristocrats in the Cotswolds, Appiah is often noted for his fluidity and grace.

This interview began in January 2020 in front of an audience at the Morgan Library. Our subsequent exchanges were by email. At the Morgan, Appiah was winning, his way of telling a family anecdote captivating. And yet this was an instance when charm was a way not of concealing but of revealing. Appiah is a liberal in the most profound sense, a philosopher whose concerns are deeply contemporary and yet reminiscent, in decency of spirit, of some of his intellectual heroes, including Mill and Montaigne. It is hard to imagine a mind of greater rigor or amplitude.

INTERVIEWER

Tell me about Kumasi and your family’s place in the city.

KWAME ANTHONY APPIAH

Kumasi is the second city of Ghana, after Accra, and it’s quite big. So, obviously, it’s not like a village where everybody knows everybody. But, given who my grandfather was, and given who my father was, and given who my mother was, pretty much everybody in town knew who we were. Kumasi is in the middle of the Ashanti region of Ghana, and my father was Ashanti—his father was the king’s brother-in-law, when I was a child, and a cousin who was like a sister to him was married to the next king. But, in part because of these connections, even though my mother was obviously from elsewhere, it would never have occurred to people to question her right or our right to be there. It was a big deal when the United States had its first biracial president, a dozen years ago, but Ghana’s head of state, for the last two decades of the twentieth century, was Jerry Rawlings, whose father was a Scotsman. He was my color, and nobody cared much one way or another.