Issue 177, Summer 2006

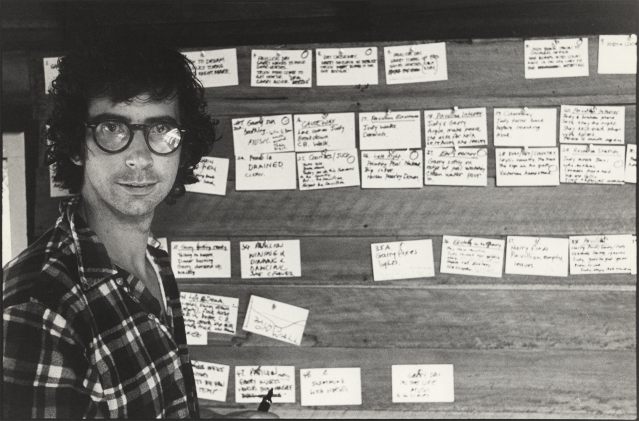

Peter Carey, Yandina, Queensland, Australia, in the seventies.

Peter Carey, Yandina, Queensland, Australia, in the seventies.

When I arrived at Peter Carey’s apartment on a chilly March morning for the first of the two conversations that make up this interview, Carey took my coat and hung it up. When we met again ten days later, he gestured toward the closet and said, “You know where the hangers are.” He is a casual man, usually found in jeans and sneakers, and given to genial profanity. For much of our four hours of conversation he reclined in his chair, his feet up on the kitchen table. But if his posture was laid-back, his expression was lively, and he laughed frequently. When talk turned to his childhood in Australia, he hopped up to show me family photographs—of his grandfather, Robert Graham Carey, an aviator, posing in a monoplane in Adelaide in 1917; and of Carey Motors, the car dealership Carey’s parents ran in Ballarat, near the small town of Bacchus Marsh, where he was born in 1943. From a kitchen drawer Carey produced a fistful of comment slips from his boarding-school days, which he displayed with self-deprecatory glee. “Very hard-working,” wrote his house master at Geelong Grammar School, in 1960. “Very intense and serious-minded. He needs to have his leg pulled and learn to laugh at himself. It may be better to concentrate on the Pure Maths next term.”

Carey has instead concentrated on fiction, with prodigious results. Since 1974 he has published two collections of stories, nine novels, a children’s book, and several short works of nonfiction, and he is one of only two novelists to have been awarded the Booker Prize twice: first for Oscar and Lucinda (1988), the story of two Victorian-era misfits for whom gambling becomes a bond of love; and then for True History of the Kelly Gang (2000)—which sold two million copies worldwide—a novel in the form of a letter from Australia’s outlaw-hero Ned Kelly, horse thief and bank robber, who was hanged at the age of twenty-six. In his recent novels Carey has explored the intersection of creativity and deception. My Life as a Fake(2003) was inspired by a notorious Australian poetry hoax. And in Theft: A Love Story, which was published this May, Carey intertwines the voices of an Australian painter, Michael “Butcher” Boone, and his mentally disabled brother, Hugh, as they navigate an international art world marked by forgery and fraud.

In 1990 Carey moved to New York, where he has lived since. For his last few novels, he has had drafts bound into what he calls “working notebooks.” The first one, made for The Kelly Gang, was “huge, heavy, and annoying to carry through the bush”; the more recent ones use lighter paper with wide margins for notes. The pages are rough (“I type so badly, it’s appalling,” he said), with passages highlighted to indicate where further research is necessary; the margins hold chapter plans and plot points, calendars and timelines, and occasionally pasted-in postcards—anything relevant to the story in progress. Though the notebooks speak to Carey's talent for weaving history and legend into his own richly invented worlds, they also illustrate his editorial rigor. “For a writer,” he says, “the greatest thing is to be able to pare away.”

INTERVIEWER

You were raised in small-town Australia—your parents ran an automobile dealership and sent you to Geelong Grammar, the country’s most prestigious prep school. What did they think when you told them you were a writer?

PETER CAREY

I didn’t tell them. I got a job in advertising. So even though I was writing, I was always supporting myself. That’s the thing that would matter for my father, who was absolutely a creature of the Great Depression. He would worry every time I got a raise. He’d think, Well, Peter can’t be worth all that money, he’ll be the first to be fired. When I finally began to publish, my father never read my work. He’d say, Oh, that’s your mother’s sort of thing. But my mother found the books rather upsetting. I figure she read just enough to know that she didn’t want to go there. I don’t think my brother read my books, but he may have started recently. My sister was the only one who read me.

None of it had to do with disapproval. My mother and father were very proud of my success. Mind you, by the time I won the Booker Prize my mother’s mind had started to wander a little. I’d gone to London, and I called her and said, Mum, you remember that prize? Oh yes, dear, she said. I said, I’ve won it! Oh, that’s good, dear. There were some people here from your work. I said, What work? I don’t know, she said—they had cameras.

A tabloid television crew had arrived at her doorstep. It was some crappy TV show. They said to her, Mrs. CAREY, you must be really pleased! Oh yes, she said, Peter always was special. They said, Did he ring you? And my mother said, Ring me? Why would he ring me? He never rings me.

INTERVIEWER

They sound like regular parents. How did they come to send you to this fancy boarding school?

CAREY

My father left school at the age of fourteen, so this was a man with no deep experience of formal education. My mother was the daughter of a poor schoolteacher—well, that’s a tautology—a country schoolteacher. I think she might have gone one year to a sort of posh school, but she would have been noticeably not well off. So you have to imagine these two people, my parents, in this little town, working obsessively hard in this small-time car business. The local high school was not particularly distinguished—I think it stopped at a certain level—and my mother was a working mother. Geelong Grammar? Because it was the best. It cost six hundred pounds a year in 1954, which was an unbelievable amount of money—and they really weren’t that well off—and they did it. So I think she thought they were doing the very best thing they could do. I suppose it did solve a few child-care problems. I never felt I was being exiled or sent away, but I was only eleven years old. No one could have guessed that the experience would finally produce an endless string of orphan characters in my books.

INTERVIEWER

Is that where they come from—your boarding-school experience?

CAREY

Well, it took me ages to figure that out. I thought the orphans were there because it’s just easier—you don’t have to invent a complicated family history. But I think in retrospect that it’s not a failure of imagination. I’m writing a book now about an orphan. But it’s also the story of Australia, which is a country of orphans. I have the good fortune that my own personal trauma matches my country’s great historical trauma. Our first fleet was cast out from “home.” Nobody really wanted to be there. Convicts, soldiers were all going to starve or survive together. Later, the state created orphans among the aboriginal population through racial policies, stealing indigenous kids from their communities and trying to breed out their blackness. Then there were all these kids sent from England to Dr. Barnardo’s Homes, which were institutions for homeless and destitute children, some of them run in the most abusive, horrible circumstances. There was one near us in Bacchus Marsh called Northcote Farm. This continued until almost 1970.

INTERVIEWER

Was that experience—of being sent off to school, of being orphaned in that way—what made you think of becoming a writer?

CAREY

Good God, no. I thought I would be an organic chemist. I went off to university, and when I couldn’t understand the chemistry lectures I decided that I would be a zoologist, because zoologists seemed like life-loving people. They looked at art, they read poetry. But I was faking my physics experiments, which is very exhausting. You’d think it’s easy enough to start with the answer and work backwards, but my experimental method was terrible. Then I fell in love and everything went to hell. Then I had a very bad car accident, which I thought was a gift from God—because it was just before final exams. I remember waking up in the wreck, my scalp peeled back, blood pouring down my face, and thinking, Fantastic, I’ve got an excuse to fail.

INTERVIEWER

What happened?

CAREY

The bastards gave me supplementary examinations. So there was no escape. But I failed all of those as well, and then I had to get a job. I finally found a job at an advertising agency. It was a strange agency, as it turns out—full of writers and artists and run by a former member of the Communist Party. It sounds ridiculous, but I worked at three different agencies all run by former Communists. If you think about it, it’s not so strange. It was Australia, not the U.S. It was after the war, and they were young intellectuals of the left. In my first job I worked alongside a man named Barry Oakley, an English teacher in his thirties who had come into advertising to support his wife and six children. He was certainly startled to find himself where he was. But he was writing every day, and he ended up being the literary editor of an Australian newspaper and also a distinguished playwright and novelist. There were also some good painters. None of us were real copywriters. I don’t think I got a single piece of copy accepted all the time I worked there. We used to write copy all day, but then our boss would come down from meetings and put on his cardigan, which was a sign that he was going to be creative, and he would rewrite everything we’d done. So Barry and I were a little hysterical because we couldn’t imagine why we were not being fired.

INTERVIEWER

What did you get out of the experience?

CAREY

I was put into an environment where people were writing and talking about books. Geelong Grammar was known as a “good school,” but this reputation turned out to be more about class than anything else. My education really began at this little advertising agency. I started to read. I read all sorts of things in a great huge rush. James Joyce and Graham Greene and Jack Kerouac and William Faulkner, week after week. No nineteenth-century authors at all. No Australian authors, because I thought they were worthless, of course—that’s good colonial self-hatred. I read haphazardly but with great passion. I would sit there earnestly annotating Pound’s Cantos, for instance, almost building a wall between myself and the possibility of reading them.