Issue 75, Spring 1979

The following interview incorporates three done with John Gardner over the last decade of his life. After interviewing him in 1971, Frank McConnell wrote of the thirty-nine-year-old author as one of the most original and promising younger American novelists. His first four novels—The Resurrection (1966), The Wreckage of Agathon (1970), Grendel (1971), and The Sunlight Dialogues (1972)—represented, in the eyes of many critics and reviewers, a new and exhilarating phase in the enterprise of modern writing, a consolidation of the resources of the contemporary novel and a leap forward—or backward—into a reestablished humanism. One finds in his books elements of the three major strains of current fiction: the elegant narrative gamesmanship of Barth or Pynchon, the hyperrealistic gothicism of Joyce Carol Oates and Stanley Elkin, and the cultural, intellectual history of Saul Bellow. Like so many characters in current fiction, Gardner's are men on the fringe, men shocked into the consciousness that they are living lives that seem to be determined, not by their own will, but by massive myths, cosmic fictions over which they have no control (e.g., Ebeneezer Cooke in Barth's Sot-Weed Factor, Tyrone Slothrop in Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow); but Gardner's characters are philosophers on the fringe, heirs, all of them, to the great debates over authenticity and bad faith that characterize our era. In Grendel, for example, the hero-monster is initiated into the Sartrean vision of Nothingness by an ancient, obviously well-read dragon: a myth speaking of the emptiness of all myths—“Theory-makers . . . They'd map out roads through Hell with their crackpot theories, their here-to-the-moon-and-back lists of paltry facts. Insanity—the simplest insanity ever devised!” His heroes—like all men—are philosophers who are going to die; and their characteristic discovery—the central creative energy of Gardner's fiction—is that the death of consciousness finally justifies consciousness itself. The myths, whose artificiality contemporary writers have been at such pains to point out, become in Gardner's work real and life giving once again, without ever losing their modern character of fictiveness.

Gardner's work may well represent, then, the new “conservatism,” which some observers have noted in the current scene. But it is a conservatism of high originality, and, at least in Gardner's case, of deep authority in his life. When he guest-taught a course in “Narrative Forms” at Northwestern University, a number of his students were surprised to find a modern writer—and a hot property—enthusiastic, not only about Homer, Virgil, Apollonius Rhodius, and Dante, but deeply concerned with the critical controversies surrounding those writers, and with mistakes in their English translations. As the interview following makes clear, Gardner's job in and affection for ancient writing and the tradition of metaphysics is, if anything, greater than for the explosions and involutions of modern fiction. He is, in the full sense of the word, a literary man.

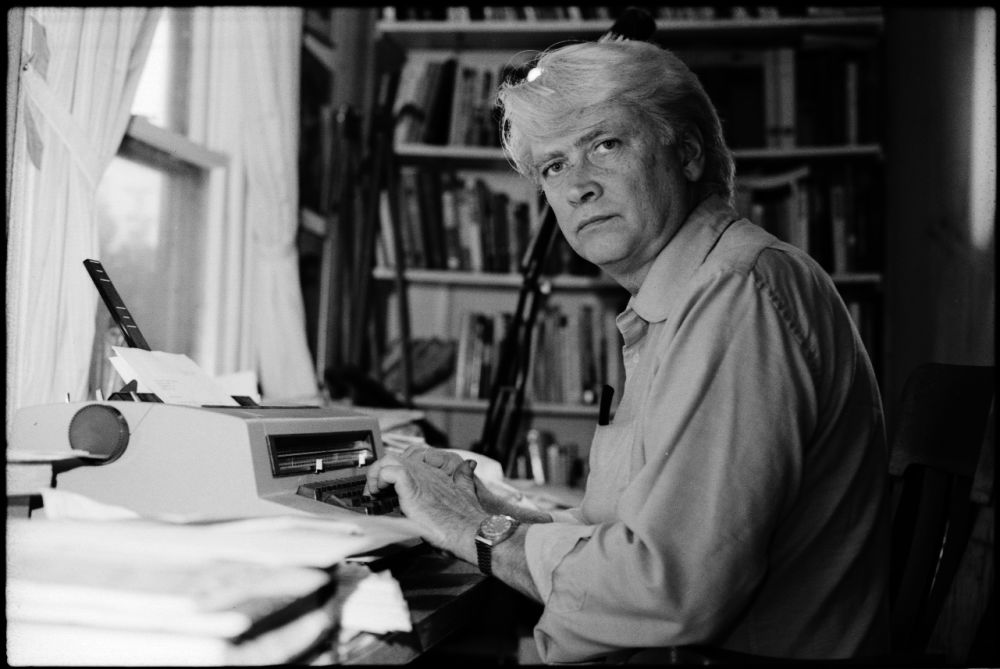

“It's as if God put me on earth to write,” Gardner observed once. And writing, or thinking about writing, takes up much of his day. He works, he says, usually on three or four books at the same time, allowing the plots to cross-pollinate, shape and qualify each other.

Sara Matthiessen describes Gardner in the spring of 1978 (additional works published by then included October Light; On Moral Fiction was about to be published). Matthiessen arrived with a friend to interview him at the Breadloaf Writer's Colony in Vermont: “After we'd knocked a couple of times, he opened the door looking haggard and just wakened. Dressed in a purple sateen, bell-sleeved, turtleneck shirt and jeans, he was an exotic figure: unnaturally white hair to below his shoulders, of medium height, he seemed an incarnation from the medieval era central to his study. 'Come in!' he said, as though there were no two people he'd rather have seen than Sally and me, and he led us into a cold, bright room sparsely equipped with wooden furniture. We were offered extra socks against the chill. John lit his pipe, and we sat down to talk.”

INTERVIEWER

You've worked in several different areas: prose, fiction, verse, criticism, book reviews, scholarly books, children's books, radio plays; you wrote the libretto for a recently produced opera. Could you discuss the different genres? Which one have you most enjoyed doing?

JOHN GARDNER

The one that feels the most important is the novel. You create a whole world in a novel and you deal with values in a way that you can't possibly in a short story. The trouble is that since novels represent a whole world, you can't write them all the time. After you finish a novel, it takes a couple of years to get in enough life and enough thinking about things to have anything to say, any clear questions to work through. You have to keep busy, so it's fun to do the other things. I do book reviews when I'm hard up for money, which I am all the time. They don't pay much, but they keep you going. Book reviews are interesting because it's necessary to keep an eye on what's good and what's bad in the books of a society worked so heavily by advertising, public relations, and so on. Writing reviews isn't really analytical, it's for the most part quick reactions—joys and rages. I certainly never write a review about a book I don't think worth reviewing, a flat-out bad book, unless it's an enormously fashionable bad book. As for writing children's books, I've done them because when my kids were growing up I would now and then write them a story as a Christmas present, and then after I became sort of successful, people saw the stories and said they should be published. I like them, of course. I wouldn't give junk to my kids. I've also done scholarly books and articles. The reason I've done those is that I've been teaching things like Beowulf and Chaucer for a long time. As you teach a poem year after year, you realize, or anyway convince yourself, that you understand the poem and that most people have got it slightly wrong. That's natural with any poem, but during the years I taught lit courses, it was especially true of medieval and classical poetry. When the general critical view has a major poem or poet badly wrong, you feel like you ought to straighten it out. The studies of Chaucer since the fifties are very strange stuff: like the theory that Chaucer is a frosty Oxford-donnish guy shunning carnality and cupidity. Not true. So close analysis is useful. But writing novels—and maybe opera libretti—is the kind of writing that gives me greatest satisfaction; the rest is more like entertainment.

INTERVIEWER

You have been called a “philosophical novelist.” What do you think of the label?

GARDNER

I'm not sure that being a philosophical novelist is better than being some other kind, but I guess that there's not much doubt that, in a way at least, that's what I am. A writer's material is what he cares about, and I like philosophy the way some people like politics, or football games, or unidentified flying objects. I read a man like Collingwood, or even Brand Blanchard or C. D. Broad, and I get excited—even anxious—filled with suspense. I read a man like Swinburn on time and space and it becomes a matter of deep concern to me whether the structure of space changes near large masses. It's as if I actually think philosophy will solve life's great questions—which sometimes, come to think of it, it does, at least for me. Probably not often, but I like the illusion. Blanchard's attempt at a logical demonstration that there really is a universal human morality, or the recent flurry of theories by various majestical cranks that the universe is stabilizing itself instead of flying apart—those are lovely things to run into. Interesting and arresting, I mean, like talking frogs. I get a good deal more out of the philosophy section of a college bookstore than out of the fiction section, and I more often read philosophical books than I read novels. So sure, I'm “philosophical,” though what I write is by no means straight philosophy. I make up stories. Meaning creeps in of necessity, to keep things clear, like paragraph breaks and punctuation. And, I might add, my friends are all artists and critics, not philosophers. Philosophers—except for the few who are my friends—drink beer and watch football games and defeat their wives and children by the fraudulent tyranny of logic.

INTERVIEWER

But insofar as you are a “philosophical novelist,” what is it that you do?

GARDNER

I write novels, books about people, and what I write is philosophical only in a limited way. The human dramas that interest me—stir me to excitement and, loosely, vision—are always rooted in serious philosophical questions. That is, I'm bored by plots that depend on the psychological or sociological quirks of the main characters—mere melodramas of healthy against sick—stories that, subtly or otherwise, merely preach. Art as the wisdom of Marcus Welby, M.D. Granted, most of fiction's great heroes are at least slightly crazy, from Achilles to Captain Ahab, but the problems that make great heroes act are the problems no sane man could have gotten around either. Achilles, in his nobler, saner moments, lays down the whole moral code of The Iliad. But the violence and anger triggered by war, the human passions that overwhelm Achilles's reason and make him the greatest criminal in all fiction—they're just as much a problem for lesser, more ordinary people. The same with Ahab's desire to pierce the Mask, smash through to absolute knowledge. Ahab's crazy, so he actually tries it; but the same Mask leers at all of us. So, when I write a piece of fiction I select my characters and settings and so on because they have a bearing, at least to me, on the old unanswerable philosophical questions. And as I spin out the action, I'm always very concerned with springing discoveries—actual philosophical discoveries. But at the same time I'm concerned—and finally more concerned—with what the discoveries do to the character who makes them, and to the people around him. It's that that makes me not really a philosopher, but a novelist.

INTERVIEWER

The novel Grendel is a retelling of the Beowulf story from the monster's point of view. Why does an American writer living in the twentieth century abandon the realistic approach and borrow such legendary material as the basis for a novel?

GARDNER

I've never been terribly fond of realism because of certain things that realism seems to commit me to. With realism you have to spend two hundred pages proving that somebody lives in Detroit so that something can happen and be absolutely convincing. But the value systems of the people involved is the important thing, not the fact that they live on Nine Mile Road. In my earlier fiction I went as far as I could from realism because the easy way to get to the heart of what you want to say is to take somebody else's story, particularly a nonrealistic story. When you tell the story of Grendel, or Jason and Medeia, you've got to end it the way the story ends— traditionally, but you can get to do it in your own way. The result is that the writer comes to understand things about the modern world in light of the history of human consciousness; he understands it a little more deeply, and has a lot more fun writing it.

INTERVIEWER

But why specifically Beowulf?

GARDNER

Some stories are more interesting than others. Beowulf is a terribly interesting story. It gives you some really wonderful visual images, such as the dragon. It's got Swedes looking over the hills and scaring everybody. It's got mead halls. It's got Grendel, and Grendel's mother. I really do believe that a novel has to be a feast of the senses, a delightful thing. One of the better things that has happened to the novel in recent years is that it has become rich. Think of a book like Chimera or The Sot-Weed Factor—they may not be very good books, but they are at least rich experiences. For me, writers like John O'Hara are interesting only in the way that movies and tv plays are interesting; there is almost nothing in a John O'Hara novel that couldn't be in the movies just as easily. On the other hand, there is no way an animator, or anyone else, can create an image from Grendel as exciting as the image in the reader's mind: Grendel is a monster, and living in the first person, because we're all in some sense monsters, trapped in our own language and habits of emotion. Grendel expresses feelings we all feel—enormous hostility, frustration, disbelief, and so on, so that the reader, projecting his own monster, projects a monster that is, for him, the perfect horror show. There is no way you can do that in television or the movies, where you are always seeing the kind of realistic novel O'Hara wrote . . . Gregory Peck walking down the street. It's just the same old thing to me. There are other things that are interesting in O'Hara, and I don't mean to put him down excessively, but I go for another kind of fiction: I want the effect that a radio play gives you or that novels are always giving you at their best.